Through the decade of the aughts, experimenters in psychokinesis navigate political and personal turbulence.

A chain reaction of events attributed to psychokinesis that raged through the 2000s had roots in a singular cosmic moment of the 1970s. Skylab, America’s first space station, was the largest spacecraft in history at that point. Astronauts traded the claustrophobic interior of the Apollo for the expansive new station, where they could eat “shrimp cocktail, filet mignon, sweet potatoes, creamed peas, and peach ambrosia” for dinner, sleep in their own quarters and take showers once a week.

But six years into Skylab’s orbit, catastrophe loomed. As reported in the Washington Post, “unanticipated atmospheric turbulence, triggered by solar activity” began pulling the then-unmanned craft toward earth. Although the craft was not designed to land intact on earth—it was meant to disintegrate into the atmosphere—it appeared to be on its way back years ahead of schedule. People feared that early reentry of the craft could cause devastation and death. Families around the world in areas identified as vulnerable panicked, with farmers selling off livestock and in some cases unloading their property in order to relocate.

The Institute for PsychoEnergetics in Brookline, Massachusetts, a grass-roots, private organization interested in unexplained phenomena, hatched an ambitious plan. “Our experiment is to see if the powers of the mind are strong enough to raise Skylab in its orbit,” said the group’s spokesman.

The group hoped to stop Skylab from crashing into the earth by using psychokinesis. The term literally means “mind movement” and refers to the theoretical ability to affect change on matter through energy produced by the mind, while the similar term telekinesis posits a mental ability to cause matter to move without physical contact. “Skylab is now circling the earth in a descending spiral,” the Brookline-based group warned. “In one future it will crash into the planet. In another future it moves into a stable orbit.” Combining the population’s psychokinetic powers could “help us to push Skylab higher and higher.”

The group partnered with WFTL-AM, a Fort Lauderdale radio station, in order to broadcast a mass psychokinetic event at 1 p.m. on Friday, May 25, 1979 with hopes of bringing a million minds together. That turned out to be a wild underestimate. With 42 radio stations across the world carrying parts of the collective psychokinesis, an estimated 12 million participated. The would-be telekinetics ran the gamut of backgrounds and ages. Children like 5-year old Kenji Ito, a Japanese boy in Yokohama, had grown up learning about Skylab and watching the sky in wonder, while the Skylab looked right back at them, snapping dramatic photos such as its views of Japan’s Island of Kyushu and the Sea of Okhotsk. Now the youthful thrills produced by Skylab turned to fear.

In the radio broadcast, the participants were primed with a meditative introduction: “There is not one time, there are many times. You and all of us are at a point in time. From this point many futures exist, not just one.” The power of collective consciousness gave them the freedom “to choose which future to manifest out of many possible ones,” but “free will is not free, it takes energy.” Then came the long stretch of silence, an intense period of concentration by millions.

The experiment lasted more than seven hours. NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston reported “absolutely no change” on Skylab’s orbit and, not surprisingly, the media pounced, mocking the participants. Two months later, Skylab careened through the atmosphere before mostly disintegrating into what a witness called “a spectacular fireworks show.” The remaining debris burned, mostly falling into the Indian Ocean and rural tracts of southwestern Australia where locals, reporters, and even Miss America, Mary Friel, searched for parts of the craft, none of which caused any injuries.

The organizers of the collective telekinetic effort admitted to feeling like failures. But for those who scrutinized the event, there was more to it. Shortly before the group’s experiment, NASA’s models predicted Sklyab’s reentry would occur between June 15 and June 22. NORAD’s models had set a 90 percent probability that the station would reenter between June 13 and July 1. The actual reentry ended up being on July 11. This significant discrepancy was omitted or buried in press coverage. Whatever unexpectedly slowed the massive object down, the dramatic difference may have changed the trajectory and kept millions safe.

The telekinetic endeavor remains unprecedented in recorded history for the sheer number of people mentally focused on one object. Part of the basis of scientific interest in psychokinesis is the notion that our brains’ functions are imperfectly understood and woefully underappreciated. Though the axiom that we use only 10 percent of our brain is a misconception, the complexity of the brain and consciousness remains a mystery even among neurologists.

It was said the brain had untapped capacity to interact with molecules, ultrasonic waves and electromagnetic forces surrounding us. The ancient thinker considered to be the father of atomic theory, Democritus, born around 460 BCE, also crystallized theories behind psychokinesis. In fact, Democritus was said to have undertaken the first field investigations of the practice. He went into graveyards and in the desert, where he could achieve solitude and test his own ability to perceive telepathically. His findings in these experiments were never revealed.

Skeptics laughed at the Skylab’s telekinetic hopefuls, but all the while scientists and officials from a wide swath of government agencies—including NASA itself—were seriously studying the potential of psychokinesis. A few years before Skylab streaked through the skies, at the 141st meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a warning sounded. Rex Stanford, a psychologist at St. John’s University, believed that psychokinesis was real and that an increase in interest was “dangerous.” Participants in experiments could become convinced they were “endowed with almost unlimited capacities to manipulate other people by psychic means… fixated on these possibilities.” By the calculus of believers, out of a sample size of 12 million people concentrating on Skylab, a few may have experienced something potent, something that knocked the wind out of them. The impact from millions of people zeroing in on that object would likely have been clumsy. But if an individual captured and controlled such powers, Stanford’s warnings could be realized sooner than expected.

By the 2000s, those fears ignited into a race to contain what some called the most powerful weapon in the world: Brainwaves.

In the spring of 2001, a researcher at the Marine Corps University named Loren Rick Bremseth, 50, prepared to shake things up. He had commanded Navy SEAL Team EIGHT, and would go on to have a major command tour at Naval Special Warfare Group THREE. Head-shaved, with a close-cropped mustache, he was tasked with handling sensitive material in tense situations at home and abroad. He was fond of one particular saying translated from 4th century Rome: “If you want peace, prepare for war.”

He was known as a teller of hard truths. He served as the Deputy Senior Director of the Integration Support Directorate, where his role included being “responsible for the synchronization, facilitation, overall planning, coordination, and execution within the DON for Sensitive Activities, Irregular Warfare, and Special Operations Forces support.” In layman’s terms, he tracked global military techniques that the public probably would never know about, methods that transcended convention. He was liaison for these matters with various agencies and officials, including the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Chief of Naval Operations, the Commandant of the Marine Corps and the Naval Criminal Investigative Service.

Commander Bremseth defied stereotypes of the hard-charging warrior who relied on brawn and weaponry over brains—in fact, he suspected brains were a potential weapon. He believed that the military’s nearly 25-year investigation into psychokinesis, part of what was known within the government as Project StarGate, had quietly been a success. But since those days of Skylab, back when the US government had been aggressively (if stealthily) funding research in unconventional fields, government support by this point dwindled, and practically dried out.

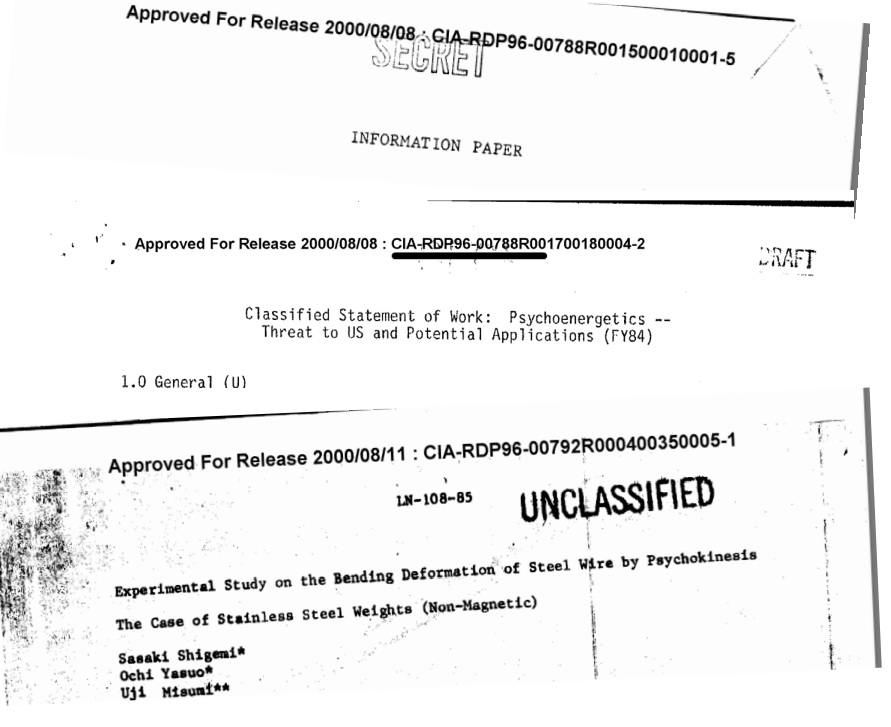

In April, Bremseth circulated a bombshell analysis titled “Unconventional Human Intelligence Support.” He diagnosed the reasons for the government’s pullback as “internal mismanagement” and political disinterest in being associated with “long-term unconventional or controversial programs.” Bremseth called the termination of cutting edge psychoenergetic research and development a “missed opportunity.” He challenged his colleagues: “Did the CIA terminate [it] because it feared potential ridicule by association[?]”

Pushing back against complacency were data points from around the world. In a declassified briefing, Project Sun Streak (an offshoot of the StarGate program) considered secretive institutes and research groups that studied young subjects with anomalous abilities. Such programs existed around the world including in Holland, France and Argentina, as well as a laboratory in Japan devoted to evaluating and refining subjects’ abilities. Researchers in Canada had examined American Indian children, and in another North American study, one 8 year old, whose identity was kept anonymous, scored off the charts in tests designed and overseen by a Duke University professor to measure extrasensory perceptions.

At a program in China, the star participants were two sisters, Wang Qiang, 13, and Wang Bin, 11, from Beijing. Results of university-led tests on the sisters were published in Ziran zazhi (Nature Journal), a respected Shanghai-based scientific journal. Researchers reported that the sisters telepathically “read” words, numbers and images without being able to see them. Telepathy—the concept of nonverbal communication or transfer of thoughts between minds—was an offshoot of telekinesis.

In one experiment, the sisters were given a sealed container with a piece of paper inside. The sisters were then able to imagine the writing “on an inner mental screen,” a fleeting image that required extreme concentration. The girls would be so exhausted by the experience that they had to rest between sessions.

From observations of telekinetic experiments, participants experienced intense respiration and heart palpitations up to 300 beats per minute. A military study that collated years of psychokinesis studies documented a woman who “suffered loss of weight, lack of coordination, dizziness, and vomiting, accompanied by bodily pain and sleeplessness,” while another woman after telekinesis sessions had “difficulty in speaking for a while afterwards, perspired freely and trembled, her eyes and nose ran.” Such physical and personal struggles could put military missions—and the individuals’ well-being—in jeopardy.

The ancient Greek philosopher Democritus defied conventions of his time by insisting that men and women who were considered prophets were indeed receiving information but not from gods. Democritus’s vision of telepathy involved a sender’s “simulacra,” an invisible entity, reaching a recipient, and, as summarized by one modern commentator, “[the simulacra] acquaint him with the view, the calculations and the impulses of the individual who is their source.”

Those who were emotionally frenetic, or perhaps those who could refine their ability to reach an almost fugue state, were the most likely to interface with these telepathic messages. The classical scholar E. R. Dodds found such the view prescient, as “a strikingly large proportion of telepathic dreams and hallucinations are reported as having occurred when the assumed agent was experiencing some physical or mental crisis.”

American researchers Paul Dong and Dr. David Eisenberg visited the facilities in China to study the Wang sisters. The girls seemed typical—precocious, gum-chewing, “average” students in school—but the American observers reported that their abilities included “restoring a torn card, removing pills from a medicine bottle by mind power, psychic writing, restoring broken chinaware, mineral prospecting, and healing.” When Chinese officials learned that the Americans had met with the sisters, they were not happy, cutting short their findings.

The Chinese military and government thought that gifted children were at risk of losing their skills over time—or at least losing control over those skills—so they instituted a program where students between the ages of 15 and 20 would undergo more rigorous training. A CIA report, declassified in 2000, noted that one researcher, Yang Chao-Tong, addressed the Fourth Plenary Session of the China Human Science Research Commission in Neimenggu, and “suggested adding attached middle schools to traditional Chinese medicine universities and colleges, and consciously accept a number of children with psychic abilities, cultivating them in depth.” Such cultivation aimed to turn those abilities over to the military.

When Bremseth submitted his 2001 report holding his peers’ feet to the fire, he was in a unique position to draw interagency attention. Bremseth put a fine point on the stakes of falling behind the curve: the government’s “inability to conceptualize transcendent warfare and to effectively develop/employ creative asymmetrical responses to dynamic environments will be recognized and exploited by our adversaries.”

Kenji Ito, who had been too young when growing up in Japan to understand the fuss around attempts to telekinetically affect Skylab, by now was in his twenties and living in London. Records of Ito’s childhood, which overlapped with the rise of Japanese laboratories studying psychokinetic tendencies in young subjects, remains difficult to piece together. He grew up disconnected from his surroundings, with a noticeable edge to his personality. A reporter who encountered him as an adult described Ito as having “a wisp of facial hair and a usually serious demeanor.”

While living in the Camden Town district, he began to feel peculiar. His head felt heavy, as if he was experiencing the blurriness of a dream while still awake. “Hypnotized,” he described it, but that didn’t quite capture his experience.

He felt as if there was someone else near him, or even inside his mind—the feeling arriving like a wave against his brain. He struggled to explain it to his wife, while worrying what she would think. Ito was far from other family and support systems. As Commander Bremseth had raised in the military context, anyone bringing up unexplained mental phenomena risked abandonment in their personal and professional lives.

A few months after Bremseth’s report came the devastation of the 9/11 attacks. Overnight, assumptions of traditional warfare had to be questioned. A flurry of proposed legislation came before Congress, including H.R.2977, a bill titled the Space Preservation Act of 2001. The stated purpose of the bill was to “preserve the cooperative, peaceful uses of space for the benefit of all humankind by permanently prohibiting the basing of weapons in space by the United States, and to require the President to take action to adopt and implement a world treaty banning space-based weapons.”

One particular section of the bill raised eyebrows. In addition to banning space-based weapons, prohibited items included “electronic, psychotronic, or information weapons” as well as the deployment of “mind control” of “persons or populations.”

At the same time, Dr. Franklin B. Mead, Senior Scientist at the Advanced Concepts Office of the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory Propulsion Directorate at Edwards AFB, wanted to understand the latest status of the field of psychokinesis. He commissioned a study centered on unconventional physics. Mead, 63, had a long and unusual career, best captured by an epigraph by T. E. Lawrence that he chose for a report on advanced propulsion concepts: “All men dream; but not equally… the dreamers of the day are dangerous men for they may act their dream with open eyes, to make it possible.” Commensurate with his philosophical approach, Mead had already flagged that the future of propulsion could include the use of psychokinesis, while other researchers conceived of psychokinesis being deployed to “bend [carbon steel] tank barrels.”

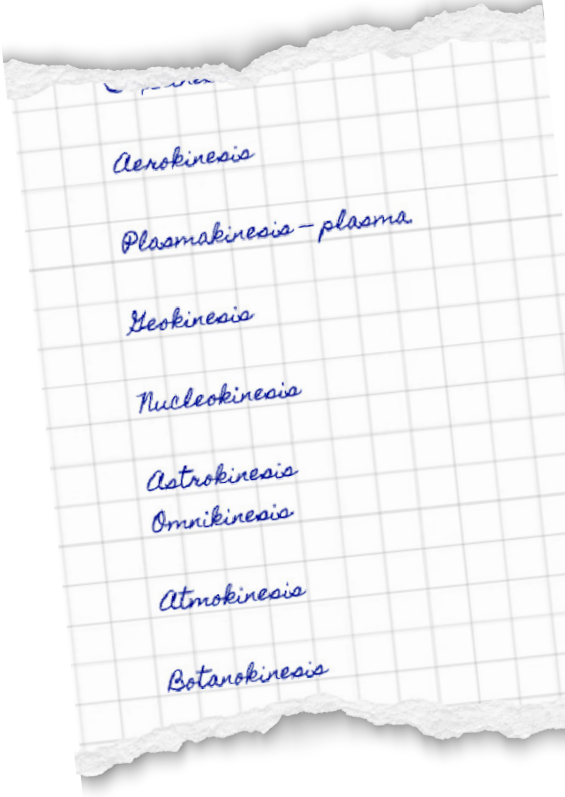

Among aficionados of psychokinesis, mental abilities could be organized into categories borrowed from physics and biology indicating impact on different types of external matter. Telekinesis was used to describe a basic ability to move an inanimate object. Electrokinesis would control electricity, and photokinesis manipulated light. Hydrokinesis mastered water, while cryokinesis affected ice. Geokinesis controlled earth, and chronokinesis impacted time. Rather terrifying to imagine, virokinesis controlled diseases.

The institutes around the world that had attempted to study and train children in telepathic techniques tended to be black boxes, making them difficult for officials like Mead to analyze. Unlike the fictional Xavier Academy in Marvel’s X-Men, children who went through real life programs were not nurtured or monitored outside experiments and tests. Some were shuttled back and forth between scientists and even between countries. The Japanese ESPER laboratory brought in highly touted “star subjects” from China, performing intense medical workups on them before permanently closing down. In China’s studies of EFHB (Exceptional Functions of the Human Body) girls who were highly touted for their abilities were believed to lose potency once they started menstruating and abruptly cut off from training. A young Russian who was studied intently in lab settings for abilities documented since her childhood, ended up celebrated before being quietly imprisoned. The individual who as an 8 year old shocked American professors with his scores on extrasensory tests pulled away from researchers once his school and home life became turbulent. Former subjects were left adrift, on their own, often confused about their own purported skills.

As programs across the globe lost funding, closed down or changed locations, some participants had been too young to remember their experiences, and even their parents could be kept in the dark. The ex-students found themselves moving on—attending universities, entering the workforce and academia, pursuing politics and activism—without clear understanding of what they had been through and why. Moreover, according to Democritus’ ancient framework, those emotionally attuned to telepathic techniques could also be most vulnerable to being targeted by them; in other cases, the “brain waves” could be released by experimental subjects unintentionally.

The mandate to carry out Dr. Mead’s commissioned study fell to Dr. Eric W. Davis, a bespectacled, salt-and-pepper haired astrophysicist who taught at Baylor University and Prescott College, and who consulted the U.S. Air Force, the Department of Defense and NASA.

Davis’s report keyed on emerging research from private citizens. One lone wolf scientist had “secretly operated” a telekinesis lab in Florida since the 1990s. Much more influential was the work of Dr. Robert G. Jahn, a physicist and Dean of Engineering at Princeton University who had founded its Electric Propulsion and Plasma Dynamics Laboratory. Jahn had a pedigree with the government, having conducted research with the Air Force and NASA.

Jahn, along with researcher Brenda Dunne, a psychologist from the University of Chicago, founded the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research Lab (PEAR), which conducted psychokinetic experiments. The lab wasn’t glamorous, located “in what was previously a small storage area next to the machine shop in the basement of Princeton University’s School of Engineering and Applied Science.” Jahn was a rigorous scholar with an appreciation for the light-hearted. Regarding their unusual acronym, Jahn would explain that he and Dunne had been at lunch, and “noticed that the salt and pepper shakers were in the shape of pears, that the salad involved pears, and that the dessert menu featured pear cake.” This moment of “Jungian synchronicity” captured Jahn’s openness to revelation.

From the start, the PEAR lab’s leadership believed that the key to understanding psychokinesis lay in a fundamental reformulation. Rather than imagining consciousness as being bound to our body, it was possible that consciousness had “a wave nature, metaphorically akin to that attributed to atomic-scale physical systems”—a striking echo of how Democritus envisioned simulacra transferring information between minds.

Jahn was proud that the lab “represented an intellectual and spiritual refuge where [colleagues] could share ideas and experiences that were discounted, or even ridiculed, by their professional peers.” Visitors included representatives of the government and military, “some of whom identified themselves as such, and some who did not.” Many government officials whose agencies had gutted psychokinetic research programs, became invested in the work at PEAR, inviting Jahn and Dunne to confer with them. Davis took particular interest in Robert Jahn “attend[ing] a meeting” on psychokinesis “at the Naval Research Laboratory” where he “warned that foreign adversaries could exploit micro- or macro-PK [psychokinesis] to induce U.S. military fighter pilots to lose control of their aircraft and crash.”

A crossroads emerged. Officials could choose to embrace a Congressional ban of psychokinetic experiments or, using the research being compiled by Mead and Davis as a springboard, could pave the way to new research—before a lack of oversight and understanding led to casualties.

In other countries, such as Romania, powerful figures openly recognized the influence of psychological anomalies. In 2004, the same year that the Davis-Mead report was released by the Air Force, Adrian Năstase was favored to win Romania’s presidential election, but claimed that he was struck by “an attack with negative energy”—a psychic attack. Some laughed. Others suspected his opponent, Traian Băsescu, was behind a nefarious plot. Either way, Băsescu won the election.

A few years later in another major campaign, Băsescu’s new opponent, Mircea Geoană, alleged that Băsescu was receiving guidance and power from an academic named Aliodor Manolea. Sporting a closely-cropped beard and a stout frame, Manolea seemed to carry the air of his former time in the Romanian army. He had two doctorates, one in psychology and another in military science, fusing together a formidable skillset. Manolea apparently made “strange” movements that were interpreted to be psychokinetic in nature. Manolea responded that he was merely coaching his candidate, noting that Băsescu had been “too passive and negative” in his public speaking.

But Geoană and his camp were well-aware of Manolea’s reputed psychokinetic talents because they, too, had hired him to work on a campaign for parliament two years earlier, seeking the same advantages. Manolea’s scholarly work openly focused on what he called a transpersonal war, an “extension of human communication” in which “the emotional, somatic state and behavior of a person can be under the mental control of another person specifically prepared to perform this action without the need for a somatic [bodily] sensory contact.”

At Princeton, PEAR continued implementing psychokinetic experiments, but under scrutiny.

Tucked among the wood-paneled walls of the nondescript lab—covered with push-pinned photographs, schematics, lists and reminders—the researchers set up subjects or “operators” in front of random event generators, known as “electronic coin flippers,” that created randomized results. As explained by the PEAR staff, “left unattended, the machine performs in a statistically normal way.” Yet when the operator was present, “wishing for the output to be higher or lower,” there was a statistically measurable difference.

In an experiment known as the Random Mechanical Cascade, a wall-mounted device that contained 9,000 black polystyrene balls dropped through a peg matrix and collected into various sections. Each section had an electronic counter that tabulated the numbers of balls that landed there. Left to run on its own, the balls would tend to collect in the center of the device, creating an almost hill-like formulation. Yet when certain operators sat on a couch across from the device and articulated intentions (“a little shift to the right”), researchers found a discernible difference from the typical results.

In another experiment, the operator stood in front of a glass-fronted device that contained a linear pendulum with an illuminated sphere at the bottom. The bob would flow at a steady rate without human presence, but in certain instances, the “damping rate or symmetry of swing” could be measured to change with particular operators, some of whom stretched out their arms and swung their hands back as they intensified intense focus on the objects.

Even a water fountain was observed to change its performance. As Jahn noted in one paper, the water’s “transition from a laminar stream to turbulent burbling,” or even its “degree of droplet scatter” were observed to fluctuate in the presence of certain operators.

Unlike the sparse institutional decor in fictional depictions of psychokinetic experiments, Jahn described the atmosphere of the PEAR lab as "cheery, relaxed, even playful," believing that psychokinetic experiences "are somehow nurtured in the childlike, limbic psyche and therefore could well be suppressed or even suffocated by an excessively clinical or sterile research environment"—hence the cartoons that decorated the walls among the scientific materials, and even stuffed animals that lined the couches.

PEAR hoped to discover how focused human intention, via thought, could influence, disrupt, or otherwise change their surroundings. In a speech to the prestigious New York Academy of Sciences, PEAR’s Dr. Arnold Lettieri explained their methodology: “Our research protocol asks people to use their minds, in accord with each experiment’s protocol. This is why we call them operators instead of subjects.” By focusing on “untrained human operators,” PEAR could demonstrate that psychokinetic ability was endemic to the brain, laying dormant and waiting to be awakened.

PEAR caught the attention of an especially vociferous and formidable critic, a colleague at Princeton. Dr. Philip W. Anderson won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1977, and began teaching at Princeton in 1984. He was known for essentially starting “solid state physics as a field.” Anderson went after PEAR on campus and in public. “I think I represent 95 per cent of the physicists I know in not believing that this kind of work is sound or worth doing.”

Jahn insisted that their apparently unconventional work at PEAR was, in fact, conventional because the foundation of science was probing the unknown. “The study of anomalies is one of the most important weapons of science—it explains where we go wrong… We have every right to study it as much as we study electrons in a cloud chamber.”

While PEAR labs deflected adversaries in New Jersey, researchers in Turkey “conducting scientific studies” in consciousness and energy research reached a milestone. They were coming together from a wide range of fields for the First Istanbul Parapsychology Conference on May 14, 2005. The meeting promised to disseminate new studies and methods among colleagues, but it also prefigured explosive developments about to unfold.

On August 8 the following year, Hüseyin Başbilen, a 31-year old mechanical engineer for ASELSAN, an influential defense corporation based in Turkey, was scheduled to present about his work on an ambitious new project: a sprawling, collaborative endeavor to design battle tanks for the Turkish Armed Forces. A graduate of Middle East Technical University, an elite university in Ankara, the capital city, his previous defense work included designing steel scopes that enabled sniper rifles to be used at night. He had just gotten married two months prior, and had high hopes for his future work and family, but he had occasionally complained of headaches.

Başbilen never showed up for his presentation. He was found dead in his locked car, parked in the street roughly 50 meters from his house. His throat and wrists were slashed; the cut on his throat was nearly 20 inches long.

The gruesome death was only the start of a series of mysterious deaths of talented ASELSAN employees working on various defense projects. Only four months later, the body of Halim Ünsem Ünal, a 29-year-old electrical engineer for the company, was found dead near Lake Eymir, also in Ankara, from a single gunshot to the head. Nine days later, Evrim Yançeken, another ASELSAN defense worker and electrical engineer, fell from the sixth floor of his apartment building. Yançeken was completing graduate work at the elite Middle East Technical University.

The cases were all ruled suicides, but loved ones pushed back. Başbilen’s family insisted the young, brilliant engineer wouldn’t take his own life. Yançeken’s family also spoke out, acknowledging the young man was stressed about his thesis, but that he was doing exactly what he wanted in life.

Months later, Burhanettin Volkan, an ASELSAN software engineer, started becoming paranoid. His father observed his son’s odd behavior: “My son seemed irresolute to me when he was at home. He thought he was being chased by snipers. He kept saying 'boom,' while pointing to his forehead with his finger like a gun. He once said that he should die instead of us.”

Volkan died of a self-inflicted gunshot. Like all of the other men whose deaths were ruled suicide, he had worked on sensitive military defense projects for ASELSAN.

Several other workers died under similarly mysterious circumstances, apparent suicides occuring without warning signs, coupled with sensitive work on secret defense projects.

Turkish neuropsychologist Dr. Nevzat Tarhan reportedly was recruited to contribute to a Turkish Prime Ministry Inspection Board report. Tarhan, with special access to the details of the cases, came forward, announcing that some kind of psychokinesis, invasive control of their minds, had led to the workers’ deaths. He urged the Ankara Public Prosecutor to consider “telekinesis as a possible cause of the suicides, which could cause severe distress and headaches in the victims, giving them a tendency to kill themselves.” For researchers who believed in advanced deployment of psychokinesis, a related possibility was that unseen assailants had been able to mentally harm the victims' bodies from afar, murdering them, or that they had used osteokinesis, the power to impact human bones, to control their movements.

For what was likely the first time in history, a government report publicly alleged that psychokinetic weapons had been unleashed against its people.

Kenji Ito, the young newlywed who had grown up in an era of covert unregulated experiments, continued to struggle in London. The voices “were constantly attached to me,” he insisted. “They were like a machine attached to me. When I’m conscious, this thing is attached to me all the time.”

He shared the experience with a friend. To Ito’s surprise, his friend did not judge him. He mentioned a nearby doctor whom he’d heard was conducting mind control experiments in London. The doctor’s name was Dr. Rupert Sheldrake, a Cambridge-educated biochemist and author. For years, Sheldrake had been writing about—and allegedly, according to Ito’s contacts—carrying out experiments related to mind control.

Ito’s marriage fell apart. He left London, and made his way back to Yokohama, where he worked a manual labor job. But his pain and fear did not subside. He continued to experience the voices that compelled him to do strange, “incomprehensible” things—and that threatened to kill him.

He went online, and learned that Rupert Sheldrake was slated to give a keynote speech at the 10th International Conference on Science and Consciousness in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Ito knew what he had to do. He bought a plane ticket, and hoped to have answers soon.

The latest Romanian presidential election was another contentious one. Mircea Geoană was running against Traian Băsescu, who five years earlier had defeated Geoană to remain mayor of Bucharest. This time, the margin between the two was razor-thin, small enough to initiate a runoff election.

The two men battled in a televised debate at Bucharest’s massive Palace of the Parliament. Geoană was feeling haggard and distracted. Băsescu won the debate and then the presidency.

Afterward, Geoană knew who to blame: the mysterious man who walked into the debate hall with his opponent. The allegation was that the academic, Aliodor Manolea, initiated a “negative energy attack” on Geoană, causing him to falter on national television.

During his presidential campaign, Traian Băsescu had taken to wearing a violet-colored tie or sweater, colors he didn’t usually wear. For those who believed in the power of flacăra violetă, or the “violet flame,” the color purple held unique psychokinetic power. The color was alleged to make “the wearer superior” and helped to deflect “evil attacks.”

Geoană’s key campaign aide, Viorel Hrebenciuc, claimed that the psychokinetic plan began during the campaign itself, well before the December runoff debate. He had observed both Băsescu and members of his campaign sporting purple on pivotal days.

Geoană’s claims of being unable to concentrate during their debates appeared within the bounds of Manolea’s purported abilities. He also seemed to channel the power of the violet flames, as several photos of him during the time of the campaign include him wearing a tie of that color.

Sometime after Băsescu’s presidential election victory, he had a falling out with Manolea, who described Băsescu as a “man who does not love his people, his family or has no respect for his own culture.” In the wake of their disputes, Băsescu was embroiled in controversies, and the Romanian parliament voted to impeach him. Băsescu complained of “fatigue and headaches” during that time, leading his staff to insist that he was the target of psychokinetic sabotage.

Stakes were high for the 2008 International Science and Consciousness conference held in Santa Fe, New Mexico at the historic La Fonda on the Plaza. As Robert Jahn had reported at the PEAR labs, government analysts and bureaucrats had been surreptitiously monitoring and attending such gatherings. This ISC conference could be a turning point, achieving a critical mass among the advocates to turn the United States into a new sanctuary for psychokinesis research. Small strides were already visible. Leping Zha, who had been a psychokinesis test subject as a teenager in China, moved to the US, receiving an advanced degree before overseeing students in experiments he designed based on his own experiences.

Government officials, professors, experimenters and former test subjects could walk the halls of La Fonda hotel together to begin what could be a new era.

A featured event of the conference was Dr. Rupert Sheldrake’s talk on “Memory and Morphic Resonance.” Sheldrake, 66, was calm in demeanor and speech, but could deliver cutting criticism of mainstream science with a well-timed smirk. A biochemist with a Cambridge PhD, he had focused his research on consciousness, including how animals tapped into a part of their brains that seemed to send signals to each other.

His concept of morphic fields echoed the foundational vision of Democritus. Sheldrake wrote of the “extended mind,” a notion of consciousness that transcended the physical body and instead “stretches” through “morphic fields,” which are “non-material regions of influence extending in space and continuing in time.”

At two points during the conference, Kenji Ito attempted to sidebar with Sheldrake. Ito insisted the biochemist had supported experiments that had gone awry and that “people were using telepathy to speak to him.” The report stated that Sheldrake said he was unable to help Ito because he “didn’t have the resources available” that “he had at home in England.”

Ito’s account differed. He claimed that Sheldrake had been dismissive of him: “I'm asking him how to stop telepathy… and he is laughing and kind of smiling like he looks at me stupid and then walks away.”

Conference attendees noticed that Ito, agitated, sat in the front row of Sheldrake’s keynote speech. When the biochemist opened the floor for questions, Ito rushed to the podium. Hunting knife in hand, Ito lunged for Sheldrake, but tripped, and stabbed him in the left thigh.

Sheldrake pulled the knife from his leg. “Every time my heart beat,” he recalled, “a fountain of blood spurted from the wound in my thigh about four inches into the air." Confused attendees scrambled in the room; several managed to pin down Ito, who one witness said looked calm and distant like he was “in a trance.”

Momentum to rebuild psychokinesis studies ground to a halt. The combined aftermath of recent international chaos—the violent personal attack at the ISC conference, the political drama in Romania, the unexplained Turkish deaths—pushed the field back into the shadows.

After it had seemed poised for breakthroughs, Princeton closed the PEAR lab in 2007. Robert Jahn had known his work and that of similar investigators would remain a source of contention for relentless critics like Professor Anderson. Jahn lamented that his project “was daunted by a recalcitrant university administration and a dearth of scholarly colleagues willing and competent to collaborate in such an enterprise.” Although he died in 2017, his partner Brenda Dunne continues to make the lab’s studies and papers available for further research. Other smaller endeavors also closed their doors, including the startup telekinesis lab in Florida.

References in Congress’ proposed legislation H.R.2977 to psychokinetic weapons ended up removed without explanation. Eventually the bill was shelved.

Some military scholars and historians who shared a school of thought with Commander Bremseth insisted that unpredictable psychokinetic battlefields had always been inevitable. The Marine Corps Gazette had noted that “fourth generation warfare” of the future will be “widely dispersed and largely undefined,” in which the human brain (according to another military report) would “be used to physically harm, sicken, or kill individuals,” unless checked by equivalent powers. These predictions held that the distinctions between war and peace would blur, as would distinctions between civilians and military. War could become constant and take place entirely via the mind, with the front lines formed by otherwise inconspicuous mindbenders and brainwave warriors scattered throughout ordinary society.

Political decision makers may be far more attuned to such predictions than people imagined. Mircea Geoană, who documented his claims that his political opponent in Romania had been boosted by psychokinetic methods, now serves as NATO Deputy Secretary General.

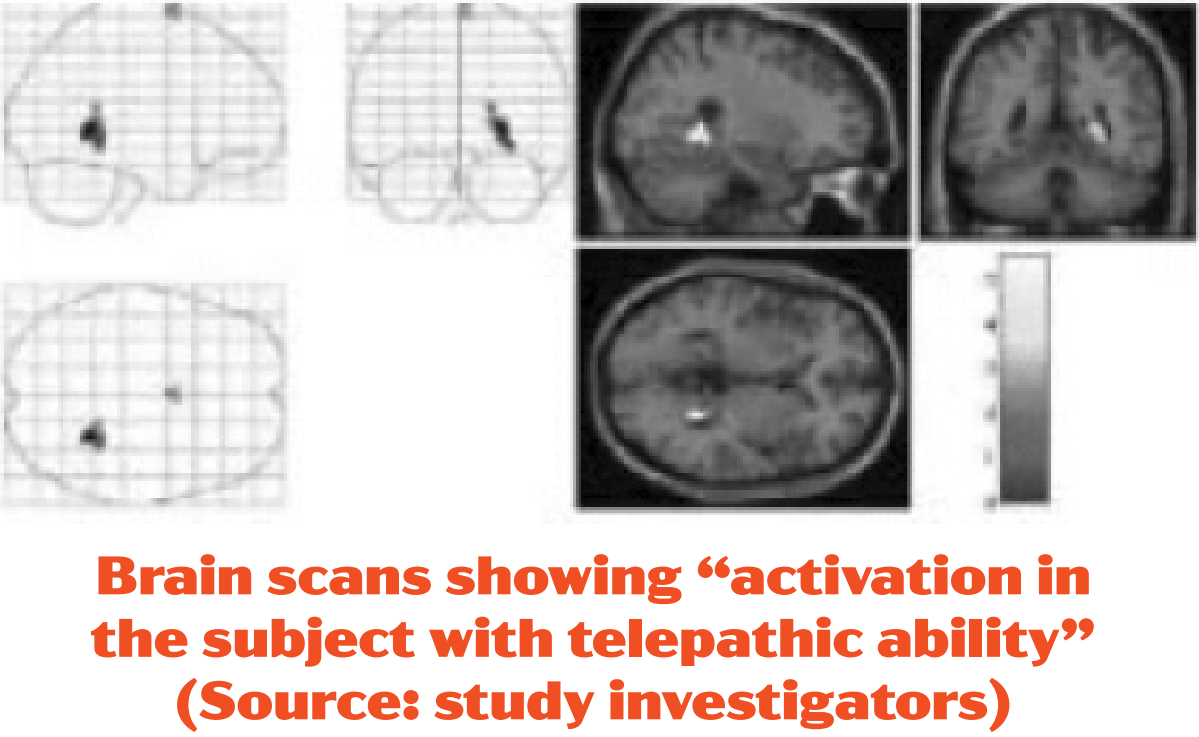

Science comes closer to Democritus’ theories as the brain’s capacity is mapped out. In India, a group of scientists used fusion imaging techniques (simultaneous fMRI, EEG, and magnetoencephalography) to chart brain activity related to psychokinetic activity, publishing findings in 2008 of “an association between telepathy and the right parahippocampal gyrus.” (This zeroed in on the same part of the brain associated with empathy and openness, also aligning with Democritus.) Daryl Bem, a professor emeritus at Cornell, in 2011 published what has been hailed as one of the first peer reviewed journal articles to lay out successful experiments showing precognition, the culmination of an eight year study involving more than 1,000 participants. In 2019, researchers at Caltech and the University of Tokyo teamed up to find the human brain could unconsciously detect changes in Earth-strength magnetic fields, demonstrating that brainwaves adjusted accordingly.

In Russia, a 2017 military report prepared by the defense ministry became public that claimed soldiers were actively training in “psychic countermeasures” and “metacontact.” “With an effort of thought,” the report read, “you can shut down computer programs, burn crystals in generators, eavesdrop on conversation, or break television and radio programs and communications… They can see through the captured soldier: who this person is, their strong and weak sides, and whether they’re open to recruitment.”

Other programs on psychokinesis remain shuttered. The personal effects on those who for many years were studied for signs of psychokinesis or who claimed to have been targets are difficult to quantify. Kenji Ito was sentenced to three years in prison. He apologized but never wavered from his original position. “I didn’t want to kill him at all. I felt I was being trapped into hurting him.” Ito insisted he stabbed Rupert Sheldrake to “try to find out who’s trying to control my mind.”

Results of psychiatric assessment of Ito were muddied. One psychiatrist thought he had traits of schizophrenia, but pointed out that he did not have the usual “disorganized thinking.” Another psychiatric counselor rejected the assessment of schizophrenia altogether. Ito was found competent to stand trial and remained imprisoned in the US until 2011. Two years later, a man who ran a website about claims of mind control received a cryptic email from Ito, who said he was being detained in the Netherlands. Earlier, Ito had pleaded to return to Japan for a “brain scan.”

In his court appearance, Sheldrake, Ito’s victim, told the court, “I investigate telepathy scientifically. I do not do it or control people’s minds.” Ito’s public defender noted that “for the first time ever in any courtroom in the world, somebody (Sheldrake) was qualified as an expert in the science behind telepathy.”

Telepathy, in a way, had been certified by a court of law.

The official retreat from psychokinetic studies repeated a long cycle. Plato reportedly feared Democritus’ ideas so much that he demanded that his writings be burned. (Democritus’ writings indeed ended up destroyed or lost.)

In a major twist, Commander Bremseth has considered that the government’s ultimate purge of funding of telepathic techniques that occurred into the 2000s may not have been exactly what it appeared. It may have been a feint. He asked: “Did [the government] stage a ‘public execution’ as a means of taking the program underground?” In other words, governmental studies into psychokinesis may well remain active, out of sight.

Off-the-books operatives didn’t have to start from scratch. They could co-op equipment and testing materials that had been gathering dust in storage, leftovers from government and private labs. They could tap into an invisible network of expertise spanning cultures, tracking down individuals trained by researchers–people like China’s Wang sisters, and the American boy who had shocked professors at 8 years old, and the indigenous Canadians who had shown anomalous abilities in their youth—a loose coalition of psychokinetic outcasts and exiles, by this point in their twenties to their forties, to be consulted, championed and mobilized.

But most former students recruited and abandoned by institutes that experimented in psychokinesis remain untallied. Living in fear of being derided and rejected, the ex-students have few places to turn for answers. For his part, Aliodor Manolea, the Romanian political gatekeeper, now teaches at the Hyperion University of Bucharest, in addition to maintaining a private practice. He welcomes pupils to perfect techniques including “deep mind control.”

Afterword

As referenced in Mindbenders, Truly*Adventurous continues obtaining rare documents and declassified CIA files. Some of the subjects of international psychokinesis experiments who stand out in these records include the following.

• A series of tests in the Netherlands showed two 10-month old babies capable of influencing the random generation of electronic numbers to present a laughing face display. (The abilities tested fall into the category of electrokinesis.) These babies would now be adults.

• Two male teenagers and one female teenager in Australia believed to have anomalous psychokinetic abilities, were tested and shown to be able to “obtain 360 degree movements of dumbbells suspended in a perspex cover under a Faraday cage.” The Faraday cage is constructed to prevent electromagnetic waves.

• Groups of third, fourth, fifth and sixth graders were placed in a competition with each other in a test of psychokinetic influence on the sprouting rye-seeds (or botanokinesis). Test results suggested the dynamic and bonds between children made a difference on the degree of measurable psychokinesis achieved on the seeds.

• Hungarian research groups conducted tests that found a small number of high schoolers were able to induce slight but measurable movement in fluids (hydrokinesis) contained in petri dishes under glass boxes. The movement started out counterclockwise, then quickly was changed to clockwise.

• A 12-year-old girl in China who would now be an adult was tested for abilities to move the hands of a watch through psychokinesis, with researchers finding the girl generated more than 100 milliwatts of pulses of power. Tools including cameras and oscilloscopes were situated to establish the reliability of the experiments.

• In an extensive observation of three English schoolboys, one (now grown) was found through telekinetic tests to be able to move a gerbil to the left and right side of a box. In the US, similarly aged elementary school students tested the ability to impact the movement of marbles and toy trucks, as well as influencing coin flips.

NICK RIPATRAZONE has written for Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is the Cultural Editor for Image.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.