Can a cowboy become the greatest polo player of all time?

—

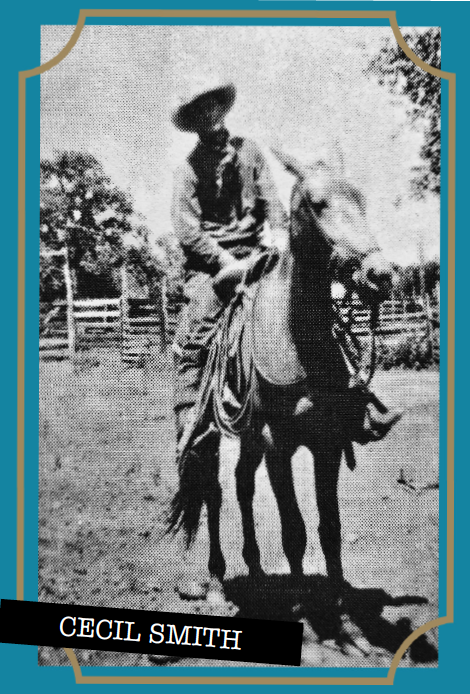

Cecil Smith, 26, lay sprawled across the grass of a Long Island polo field, hundreds of miles away from his home. He had been called an outsider (which, to be fair, he was), an invader (also fairly accurate), and he’d been told he would never compete with the best of this game. He wasn’t conceding that last point, however. The cowboy from Texas had barreled into the exclusive sport of polo, wearing dirt-encrusted boots and wielding a blazing mallet, determined to prove himself.

He was never supposed to get this far. Now everyone in the stands held their collective breath as he lay crumpled on the ground. Polo was meant to be a sport for insiders, for kings. Cecil’s sturdy shoulders carried the weight of demonstrating otherwise, and now it appeared he might never have that chance. Cecil had defied expectations before, over and over again, in a march to prove wealth and heritage couldn’t padlock opportunity forever. If the doors to polo could be pried open by this underestimated cowboy, then every American could dream big. But first Cecil Smith had to get up, and he wasn’t doing that.

A few years earlier, Cecil offered up a dazzling show of raw talent that put him on the map, driving the herd down the 300-yard-long field at the Detroit Polo Club toward the goal posts. Three finely booted opponents galloped behind him, doing their best to cover the young phenom and stop the drive. But the upstart with the dusty boots eluded them. Cecil knocked the ball to a teammate then rode hard toward midfield, setting up the old give-and-go. The teammate passed the ball back to Cecil. It rolled to a stop ahead of him but on his left side—he played right-handed. His opponents saw no way for Cecil to get his mallet on the errant ball, and they adjusted their course to steal it.

Detroit’s 1925 polo set had never faced a horseman—an honest to God cowboy—like Cecil, and he was hellbent on getting that ball. He telegraphed his demand to his pony, which seemed to leap 10 feet sideways, astonishing the pursuing players. Cecil, after all, had learned every trick as a horse trainer on a Hill Country ranch where he’d been born in a two-room shack in 1904. He was working as a wrangler on that same ranch when a friend named Rube Williams explained to Cecil that he might earn extra money by training horses for polo; Cecil had become renowned as an extraordinary horseman. But first Cecil would have to understand the sport itself. Rube had picked it up from his boss, a notoriously gruff Austin horse trainer who’d soon be employing and teaching both Rube and Cecil. “The first time you hit that white ball and see it rolling, you’ll be hooked,” Rube promised him.

Cecil made his first mallet out of a broomstick and used empty tin cans and rocks instead of balls. Rube helped him learn how to balance himself in the much smaller English saddle while galloping and spinning around. With their boss and another trainer, they went on to form the Austin Polo Club team and swept the Southwestern Circuit.

At the Detroit Polo Club, Cecil’s background shone as his pony seemed to respond to his very thoughts. Cecil stood high in his long Western stirrups; he had not adopted the shorter English stirrups considered more proper for polo. With his right hand, he raised his mallet overhead, poised like the hammer of a cocked pistol for the split second it took his horse to deliver him to the ball. Then he began his backhand swing: The long, flexible shaft bent as it swept toward the ball, cracking it off the green grass and into air, toward the far goal.

In the stands, the film star Will Rogers, a polo player from humble roots himself, marveled at the skill of the player who so obviously must have had one heck of a story to get as far as he had from home. Rogers would make a point to get to know who this new sensation was.

The opposing players shook off their disbelief and gave chase, but it was too late. The pony thundered toward the ball. Cecil cracked it off the ground again, sending it through the air like a bullet. It sizzled between the goal posts. The entire sequence, and other feats like it, left his opponents dumbfounded. How the hell did he do that?

It was one thing for this dirt-poor cowboy to find his way into the match. It was another for him to wipe the floor with his superiors. The old guard would have to pull ranks. This barbarian, who could ruin polo, had to be stopped.

Louis Ezekiel Stoddard, 52, the scion of a banking family, was worth $50 million in today’s money as he presided over the United States Polo Association in 1930. The balding patrician played polo with all the best riders from the best families of the Northeast. To a man with Stoddard’s vantage point, Cecil Smith was anathema to the elite world of privilege their sport helped to preserve.

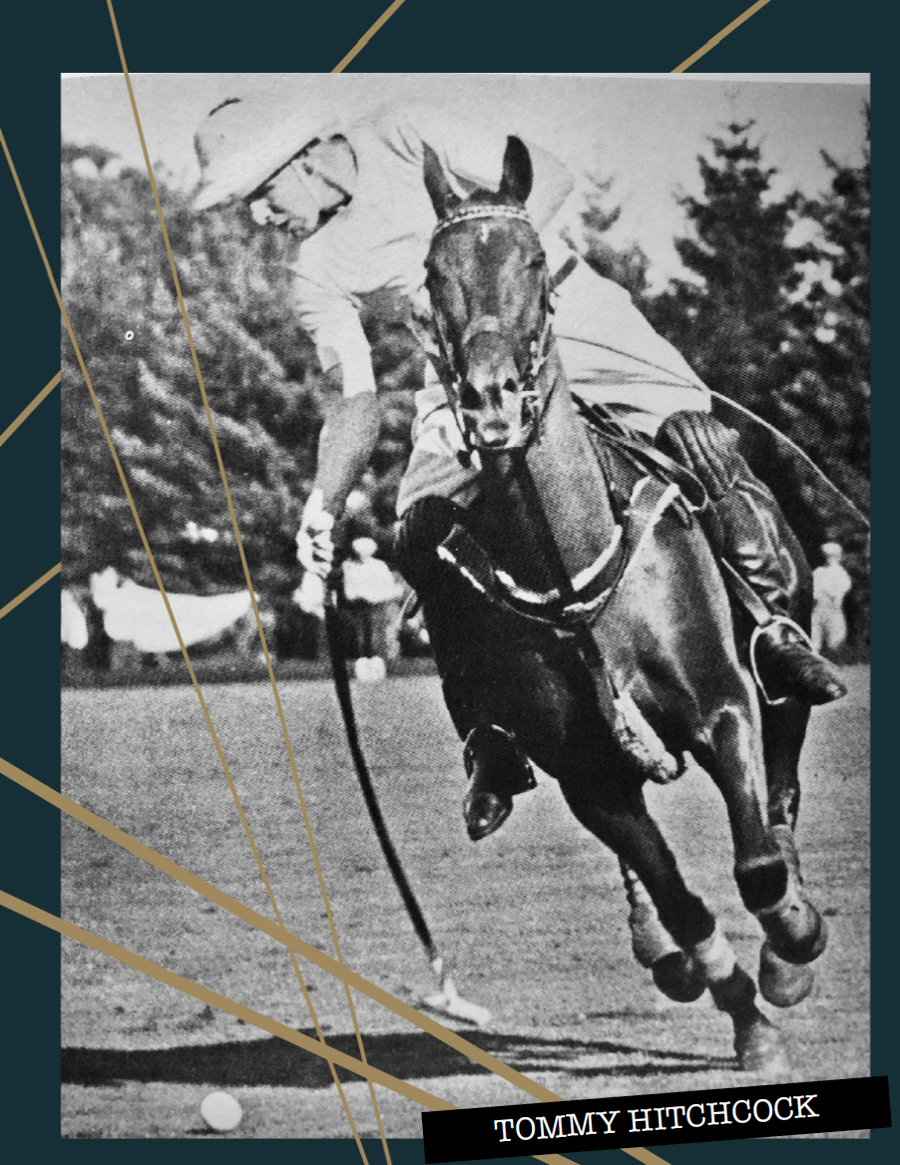

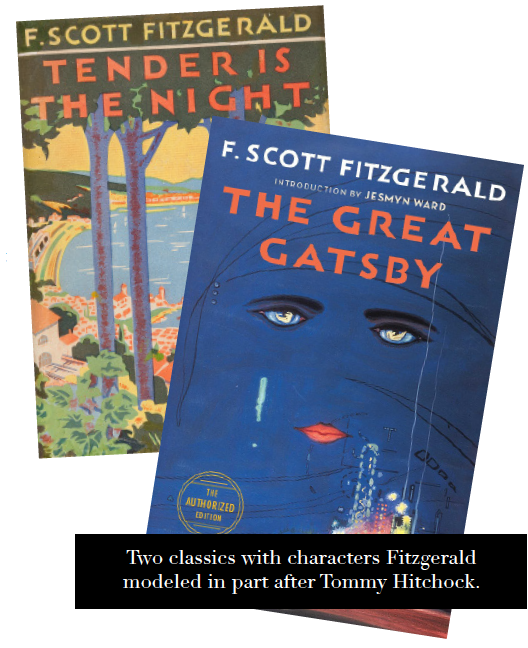

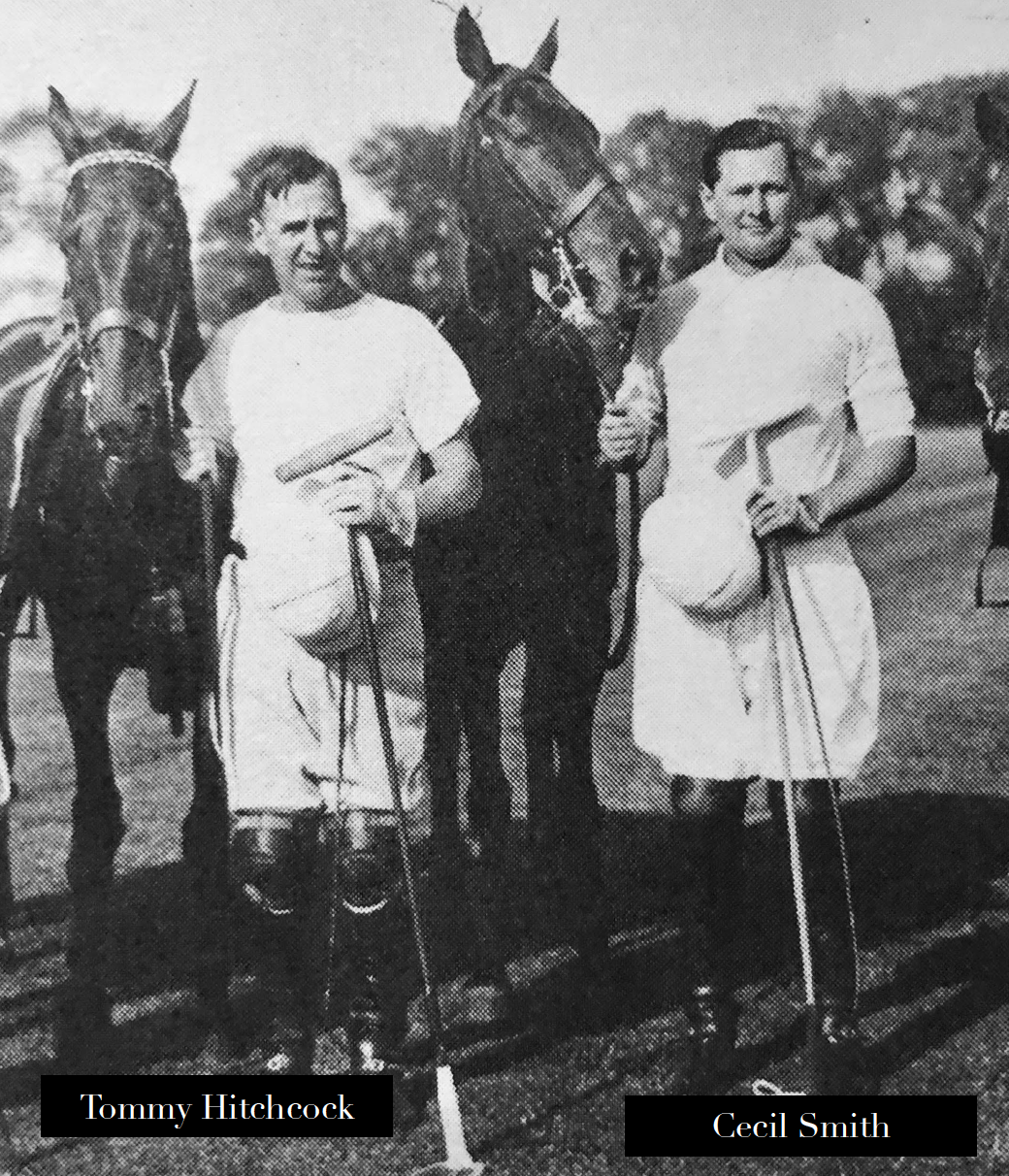

After watching Cecil’s scorching play in Detroit, Will Rogers had gone on to invite the prodigy to one of his shows, sparking a friendship that would help make Cecil a national sensation. Still, none of that impressed Louis Stoddard, who reigned over his domain from the Meadowbrook Polo Club, a sprawling and exclusive estate on Nassau County, Long Island, that boasted the neoclassical columns and arched windows of a palace. This was the realm of polo royalty, like all-star rider Tommy Hitchcock Jr. Tommy was a wealthy native Long Islander who had become a hero of World War I with the famed Lafayette Flying Corps. Eventually shot down behind German lines, he was captured, but made an astonishing break from a prison train and trekked 100 harrowing miles to freedom. He had long been a Ten Goal-rated polo player (out of 10), and he had even won an Olympic silver medal in the sport in 1924. Tommy could appear to be either a quintessentially straight-shooting American guy or a loner with a set of life experiences few could fathom. This appealed to F. Scott Fitzgerald, who modeled not one but two characters in novels after him. Most recently, Tommy Hitchcock led the United States polo team to victory against the British for the 1927 International Polo Cup, held at Meadowbrook. Tommy Hitchcock was polo.

The closest Stoddard would allow Cecil Smith to polo was the yard in front of Meadowbrook, where he let the cowboy sell his best ponies to club members. They would ride the ponies to victory inside the gates of Meadowbrook and around the world. Undeterred, Cecil kept competing—and winning. By 1930, no longer a newcomer or a journeyman horse trainer, he carried a seven-goal rating from the USPA, which meant he could technically play among the best. He would even marry the daughter of a prominent Long Island banker. Stoddard felt that Cecil Smith was breaking too many unwritten rules off and on the field. A reporter wrote the words that Stoddard would not say directly: “Long Island has long been the capital of polo in this country, and a very hard capital for an outsider to crash. It is there that the United States teams have been chosen for International competition, and, singularly, almost all of the players have been Long Islanders.”

Then a private, three-word directive reached Stoddard. Let him in. This came from an unexpected source: Tommy Hitchcock. Stoddard could not say no to Tommy, the sport’s star. The USPA patriarch agreed to a minor concession. He would not actively try to keep Cecil off of his field, but he would never go out of his way to help. Maybe there was a silver lining to

Tommy’s intervention, one that Stoddard relished: The best player in the game could now show the world that Cecil Smith did not belong.

Stoddard soon got his match-up at Meadowbrook. It was during the ensuing 1930 U.S. Open where Cecil took the hard blow to the head. The end to all Cecil’s ambitions, to all those everyman hopes, seemed to have come swiftly with that moment. Cecil was out cold and, after suffering a heartbreaking 9-10 loss, his team was already out of the tournament in the first round. His teammate and old friend Rube helped him to the stable to recuperate. Cecil also had entered himself into an additional competition at Meadowbrook that weekend, but it was a less prestigious outing and it was not clear that he would be in any shape to play polo again. Would it be worth riding with perhaps a concussion, for a lesser prize, even if he could? It was enough to cause his head to ache all the more, but it was noise outside his head that got his temples pounding.

The footsteps echoing off the stable aisle, coming closer, would have felt like a hammer striking against Cecil’s throbbing brow. Someone asked how he was doing. Cecil sat up as fast as his injury would allow. There was Tommy Hitchcock. “I figure any man fool enough to play this game does better with his brains knocked out,” Cecil replied.

Tommy took the measure of Cecil. Who you were when your best plans went awry offered the best indication of your real character. Tommy did not mention anything about how his sway had helped get Cecil into Meadowbrook. If he had any deep thoughts about the cowpoke’s ability or prospects, he kept them to himself; he just wished Cecil well and left.

The two met again several days later, this time on the field and in the finals of the Monty Waterbury Cup, a concurrent competition at Meadowbrook. No one could have been more amazed than Tommy to see Cecil saddle up and ride out for the finals after that injury in the U.S. Open. But Cecil was finally playing in Long Island, and he could not–would not–forfeit another opportunity to make his name. He would not waste an opportunity to ride against his biggest rival, on his rival’s home turf. Cecil’s tenacity was reminiscent of the drive possessed by Tommy himself. Now the time had finally come for these two titans to meet head-to-head.

With some trepidation, Cecil watched the very man who inspired F. Scott Fitzgerald’s description of polo player Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby: “Not even the...swank of his riding clothes could hide the enormous power of that body—he seemed to fill those glistening boots until he strained the top lacing, and you could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat. It was a body capable of enormous leverage—a cruel body.” Tommy Hitchcock sat lightly atop his pony holding his long torso raised. His short, powerful legs were clothed in white breeches that gleamed in the autumn sunshine. The proportions of his torso and legs made him the perfect specimen for polo. He wore a white helmet with a brim that nearly covered his eyes. His pony’s mane was perfectly shaved; its tail braided into a thick two-foot-long bob. Its legs were wrapped in white from cannon bone to hoof.

Tommy and his Greentree team were defending champions, and 7,000 of their fans had gathered to see the squad, which carried two members of the 1924 U.S. Olympic Team--the last time polo had been included in the trials. Here was Long Island polo itself riding out to vanquish Cecil and Rube, two cowpokes from the Hill Country who’d made it onto these private fields of privilege.

When Cecil encountered Tommy on the pitch, gone was any of the compassion he may have sensed during their brief visit. Gone was the quiet gentleman adored by the press, the ambassador of polo. A relentless competitor now abided; Tommy rode to win.

Since Cecil played the No. 2 position, he would have responsibility for offense as well as covering the opponent playing the No. 3 quarterback position, which was almost always the best player on the team. Today, in their first meeting, Cecil would cover Tommy Hitchcock.

Of the other character Fitzgerald derived from Tommy, that of Tommy Barban in Tender Is the Night, the novelist wrote, “Courage was his game and his companions were always a little afraid of him.” Cecil Smith quickly would have understood where Fitzgerald was coming from with that description.

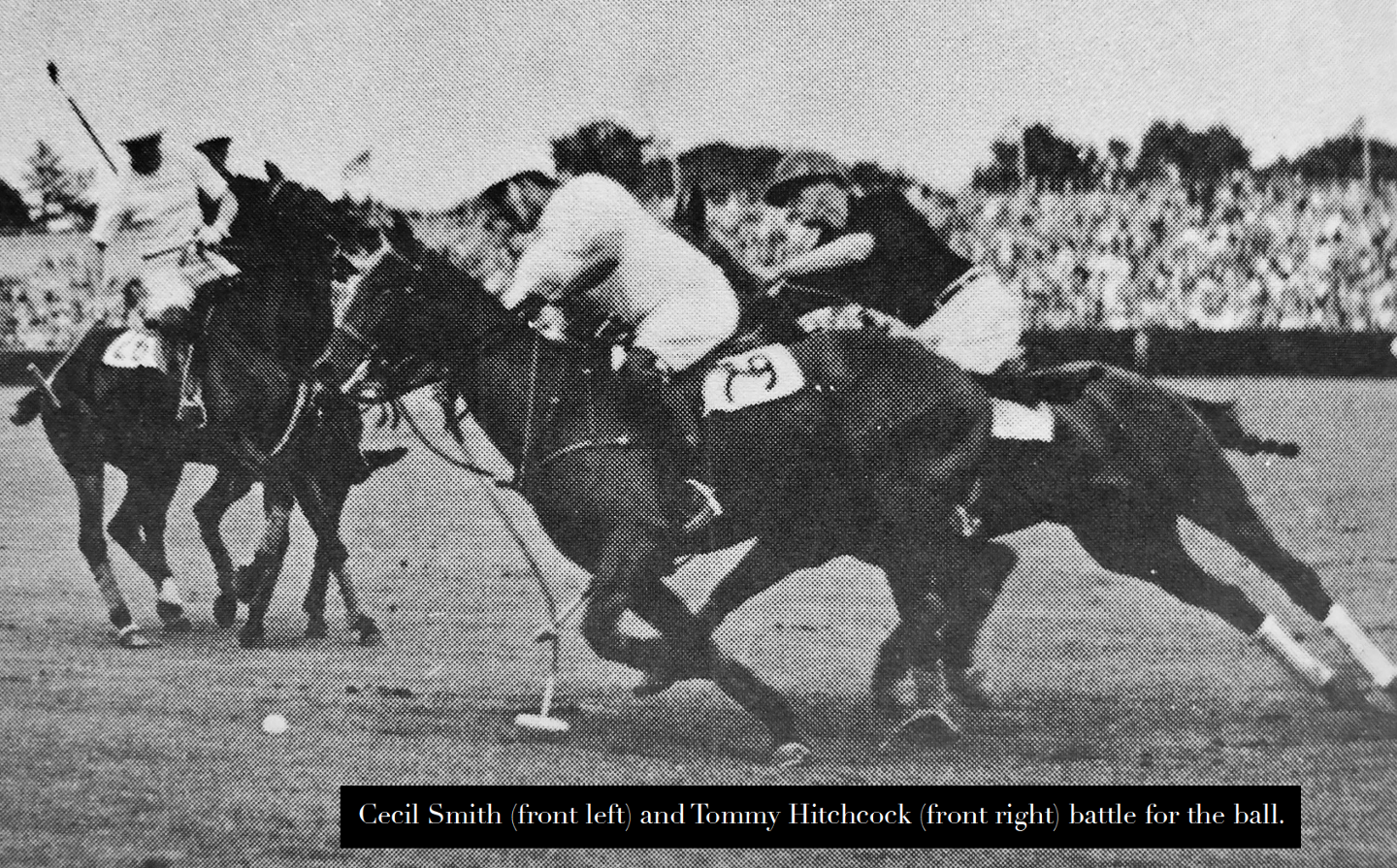

Cecil’s team, called Roslyn, scored quickly and tallied three times in the first chukker, or period. During the second chukker, Cecil was chasing the ball toward the goal when he spied Tommy to his right, barreling toward him from approximately 2 o’clock. My God, is he going to stop? It seemed not. Cecil jerked his horse off course and away from the ball, which was Tommy’s plan. At the same moment, Tommy reined his horse hard and veered off, ending his charge just short of Cecil’s right side. Cecil swore Tommy winked at him.

The referee ended the 7 ½ minute chukker shortly afterwards, signaling a four-minute break. The score stood at 6–0 in Roslyn’s favor. Disbelieving fans would have wondered, “Who were these invaders?”

At the horn, Cecil and Tommy turned abruptly and raced to their respective trailers. Their ponies arrived sweaty and tuckered, streaks of froth covering their glistening bodies. Grooms took the reins of the exhausted mounts in one hand and with the other handed the rider his fresh pony. The players took a breath before racing back out to beat the clock. Few players had kept Tommy in such check for so long, and he burst forth on his fresh horse with determination and what must have bordered on fury. He tried to turn the tide single-handedly, with dogged determination. As Tommy drove his team toward the goal, Cecil gave chase, trying to beat his mark to a rolling ball. One of Tommy’s teammates rode ahead of them and angled to hit the ball.

“LEAVE IT!” Tommy thundered. The air and the other seven players shook at the booming order. Cecil had never heard a command like that, carrying such authority and volume that it seemed to split the air.

Tommy’s startled teammate veered away from the ball and allowed the star to surge forward at full gallop, standing in his stirrups. The energy of mallet, horse, and rider

converged on a single point of impact to send the ball rocketing through the goal posts, which were nearly 100 yards in the distance.

The darting horses and persistent defense of the two Texans and their teammates managed to stifle the surge, and Roslyn held Greentree to two scores in the third. The next chukker saw Cecil’s team resume the attack and knock in three goals, running the score to 9– 2, a deficit even Tommy Hitchcock would be hard pressed to overcome.

Cecil and Rube methodically worked their opponents like they had worked Hill Country cattle years ago, methodically and consistently. The ensuing chukkers revealed that the aristocrats were human and fallible, and the Texans had a quite workmanlike style of domination. Cecil learned Tommy’s game and held Greentree’s Ten Goal ace to two scores. The Western ponies ridden by Cecil and Rube also had a thing or two to show the Long Islanders. Cow horses had to move nimbly through herds, responding quickly to corner scared calves or jumping sideways to evade charging bulls. They were fearless, agile, and sensitive to their riders--everything a great polo pony also needed to be.

At the end of all eight chukkers, Cecil had scored four goals and racked up even more assists. The cowboy beat the king 15–6 in their first head-to-head match. Cecil had won his first major victory on his way to becoming a fixture of the sport. For Tommy, accompanying the sting of defeat was deep satisfaction that a rival deserving of the victory had emerged.

The New York Times reported, “From first to last, almost without a break, the Roslyn team outplayed the losers….the Texan, Cecil Smith, was a superb No. 2, hitting beautifully and riding all over the field to score four times himself and set up others.”

Cecil received the Monty Waterbury Cup trophy from Mrs. Tommy Hitchcock Sr., Tommy’s mother and a great equestrian herself. With the trophy, Mrs. Hitchcock finally granted Cecil entrée to polo’s most prestigious clubhouse, and he walked his cowboy boots right in.

After Cecil won the Monty Waterbury Cup, Louis Stoddard could no longer avoid giving the Texan his due. In fact, he organized the famous 1933 East-West Challenge in Chicago, held in front of more than 50,000 fans, where Smith and his patron-rival Hitchcock faced off once again. More tickets were sold to the East-West Challenge than to the first Major League All-Star Game, held that summer in nearby Comiskey Park. The three matches were broadcast to millions of eager listeners around the Depression-weary country.

A nation of underdogs followed along live as their champion, the unlikely Cowboy, once again proclaimed victory over the King. Will Rogers, announcing the win, gloated, “Well, the ‘hill billies’ beat the ‘dudes’ and took the polo championship of the world right out of the drawing rooms and into the bunkhouse!”

Cecil Smith proved that his ascendancy was no fluke. With this victory, he finally earned the USPA’s coveted Ten Goal rating. Together, Tommy Hitchcock and Cecil Smith dominated their sport for an unheard of forty years. And for the rest of their lives, each called the other the greatest polo player who had ever lived.

ALVIN TOWNLEY is an assistant professor of Leadership Studies at the University of Richmond. She writes about Black life in the early twentieth century.