A hit job and a murder. In Festus, Missouri, no one knows who to believe.

TIM TODD spent a quiet and, by all appearances, happy weekend with his wife, Patti. First thing Monday he went to meet his boss, private security kingpin Bill Pagano, to solidify his plans to have her killed.

They sat across from each other in Bill’s office.

“Did you go up to St. Louis last night?” Tim asked Bill expectantly.

Bill nodded. “It put me right in the middle of where I didn’t want to be,” he said.

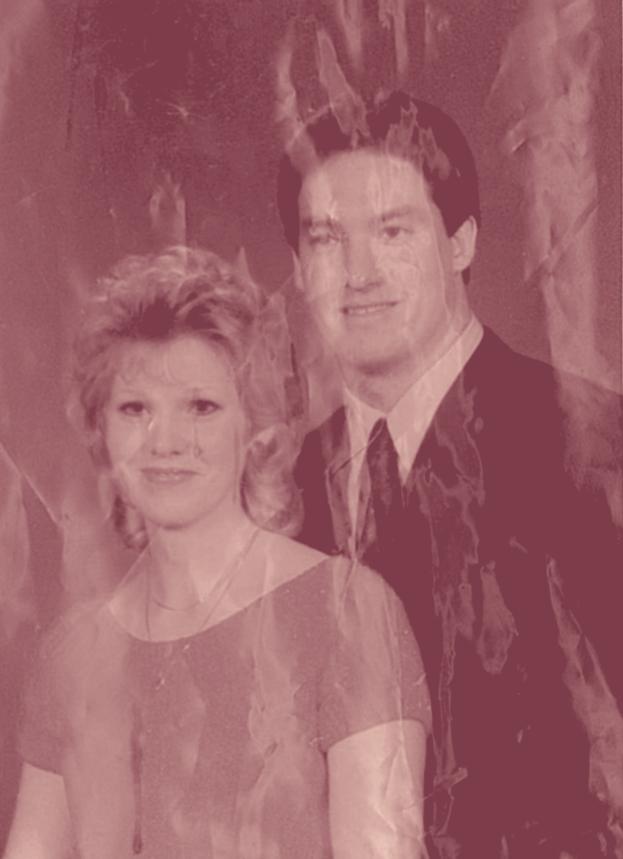

Tim Todd and Patti Todd

Bill, the former police chief of the small town of Festus, Missouri, said he had gone to St. Louis to rendezvous with a pair of hitmen who Tim was convinced would solve all his problems.

“[The hitmen] are taking this on my love for you, okay?” Bill said. “And you know, conversely, they’re believing everything I say about your love for me.”

Bill was in all likelihood thinking about the years he’d covered for Tim. Bill was Tim’s mentor. And Tim was Bill’s right-hand man. Over the past decade their fortunes had risen together. They could fall together just as easily. When Bill got wind that Tim had been running around Festus trying to find a hitman to kill his wife, he chastised his young protégé for the loose talk and for not coming to him first.

“Which package do we have to deliver today?” Tim asked.

“The picture.”

“This is the best my mom’s got,” Tim said. He handed over the photo, a Sears-style portrait of Tim and Patti. She wore a red dress and a half- smile, her blonde hair falling at her shoulder. “Her and me together. And that’s about close to what she looks like now anyway.”

Bill took the photo by its edges. “It don’t matter if your prints on there,” he said. “But if it’s got mine, that’ll raise questions.”

“Do you want me to cut myself out of it?” Tim asked.

“It looks more authentic if you’re in it,” Bill replied.

Their voices were cautious, controlled. They knew each other even better than their own families did. But the chummy brotherhood was a veneer. Bill was recording the conversation with his protégé to bring to his friends in law enforcement. The events already in motion would soon draw the attention of the entire Midwest to this small town on the Mississippi River. With toppled allegiances, unforeseen betrayals, and a small-town multi-business empire that made a mockery of law enforcement and government, this murder-for-hire scheme would spur an unexpected turn for the would-be mastermind.

Tim said he planned to be in Cape Girardeau, 80 miles south, the following weekend competing in the body building meet he’d been ferociously training for. He was bringing his two kids with him, but not Patti. It would be a convenient alibi and a way to make sure neither of his children were caught in the line of fire.

“I’d be real surprised if they jump that fast,” Pagano said, referring to the hitman in St. Louis. “But, maybe they will.”

BILL PAGANO carried himself with the air of a nobleman. In Festus, population 7,000, that’s essentially what he was. He had been the youngest police chief in Missouri when elected at age 27. Legend has it that on his first day he issued an ultimatum to the motorcycle gangs that plagued the town at the time: leave Festus before sundown or else. The gangs responded by breaking Bill’s jaw outside a biker bar. That night he arrested every biker, whether they’d committed a crime or not.

The story may be fiction, but either way it speaks to what Festus residents say were the defining traits of Bill’s tenure as police chief: his ability to rid the town of riffraff and then quickly spread word of his having done so. He was a gregarious raconteur whose stories tended to be about himself. Later, he convinced the city to give his officers substantial raises, which in turn made the force fiercely loyal to him.

He also persuaded Festus’ mayor to let him start a private security company even as he was still police chief. He procured massive public contracts that grew his wealth. In 1984, he quit his job as chief, quipping: “Right now my police work consumes 90 percent of my time but is only 10 percent of my income.” Because his salary as police chief was public, the math was easy. Many interpreted the quip as the typical braggadocio they’d come to expect of Bill.

Bill Pagano

He was a big shot in a small town, and there was no one in the county who wouldn’t answer his call. So when he rang Jefferson County Prosecuting Attorney William Johnson and asked him to lunch at the Raintree Country Club, the prosecutor quickly agreed.

After lunch the pair went back to Johnson’s office, where Bill had a sensitive matter to discuss. About a month earlier, he informed Johnson, he had taken the unusual step of drilling a hole in his office desk to wire a microphone so he could secretly record ongoing conversations with his second-in-command, Tim.

“I have a very serious problem,” Bill said.

He told Johnson that his friend and right-hand man wanted to have his wife, Patti, murdered. He’d confided as much to Bill and talked about recruiting hitmen to do it. Bill had told Tim he could help in order to draw out a confession. Bill told Johnson that he loved Tim like a son and didn’t want to see anything bad come to him or to Patti. He also indicated he had Tim’s entire plan on tape.

“He’s so loyal and valuable, just a friend. He got into trouble when he was with the police department and had to resign,” he said. “He had a psychiatric episode.” Bill told Johnson that Tim, a fitness freak, was using steroids. Bill believed the steroids were now causing another episode and were the reason Tim wanted his wife killed. He was a good kid who was making a mistake.

“Would you consider deferring prosecution if I could get him into a hospital, a psychiatric unit?” Bill asked. “I would take him to Kansas City or Chicago.”

Johnson thought about this. On the one hand, as prosecuting attorney he had wide discretion if and how the state brought charges. He felt that Bill was sincere in his desire to see no harm come to Patti, and Johnson said that was his top priority as well. But he worried Bill’s desire to keep Tim out of trouble could wind up getting Patti killed.

Bill told Johnson about the bodybuilding meet in Cape Girardeau. That was when Tim wanted the hitmen to do it, providing him with an alibi.

OK, Johnson thought. That gives us an eight-or-nine-day window. Bill asked, “What about if I just brought him in myself?” “That would be dangerous,” Johnson replied.

“I could ask to see his gun.”

Johnson later said he was skeptical of the idea but felt it was not without its merits. Crucially, Tim had at this point committed no crime by merely talking about killing his wife. Johnson saw, however, that Bill was in the unique position of being able both to confirm Tim was serious about killing his wife and to arrest him for it. More specifically, Bill could facilitate the transfer of a significant amount of money—say $5000—from Tim to hire a hitman. In doing so, Tim would actually be committing a crime, and Bill, who was still an auxiliary deputy, could arrest him.

Johnson didn’t sign off on the plan outright, but he didn’t forbid it either.

Bill left the prosecutor’s office, evidently satisfied. But evidence would later suggest he had his own plan brewing.

TIM ENTERED Boatmen’s Bank and wrote a check for a $5,000 cash withdrawal. He had no choice, he believed. He was going to go through with it.

He’d already offered $10,000 to his lifting partner Dennis Rozniak to kill Patti. He said he didn’t care about the method as long as the job got done. But Rozniak rebuffed Tim’s offer. “I’m not going to do that to your kids,” he told his friend.

Tim then asked another workout partner, Francisco “Frankie” Perkins, if he knew any hitmen.

Tim told him he had $10,000 allocated for the hit and that Perkins could keep $2500 of it if he could find someone who’d do the job for $7500.

Perkins also wanted nothing to do with it. Bill would be Tim’s only remaining confidante.

Tim had a history of acting erratic all over Festus. It had been his erratic behavior, in fact, that first put him and Bill on a collision course.

Tim had been a young second-year officer on the town’s police force when he left his patrol car in the parking lot of KJCF, a local AM talk radio station, and walked into some nearby woods carrying his bullet proof vest. He latched the vest onto the stump of a tree, stepped back several yards, and with a .357 Magnum put two slugs into the armor.

Then he took a hammer and swung it into his own chest. Tim strapped the damaged vest back on his own body and from his patrol car called dispatch.

“Shots fired. Officer down.”

When backup arrived they found Tim lying on the ground next to his car.

Tim told his fellow officers that he had encountered a man and woman having sex in a van. After an altercation with them, the man grabbed Tim’s service pistol and shot Tim twice. He wanted a harrowing story that reflected his heroic idea of himself. He might have gotten away with his fake shooting stunt if he’d just shut up about it. Instead, he went on the local amateur speaking circuit, recounting his brush with death to whatever audience he could find, at churches mostly. Up by the altar he’d hold high the bullet proof vest he himself had shot. It’s through god’s grace I’m here today, he’d say. God took this little bit of Kevlar and worked a miracle.

Bill was the Festus police chief and Tim’s boss at the time. He ordered Tim to St. Louis for a psychological evaluation. When Tim flunked it, Bill kicked him off the force. Still, the older man took pity on the fit and energetic—and not to mention unscrupulous—Tim. The staged shooting, in a twisted way, emboldened Bill to become Tim’s mentor and benefactor, and to shape Tim into his right-hand man.

The timing was good, too. Not long after firing Tim, Bill started the private security company SSI Global. The “Global” was a bit aspirational, but within a few years Bill was leveraging his position as chief to win big security contracts across eastern Missouri, making him a millionaire many times over, by far the richest man in town.

Tim’s salary was $60,000 a year, double what the average man in Jefferson County earned at the time. “It’s a little more than he’s worth,” Bill reportedly said. “But he’s so loyal.” Bill soon employed more than half the police department and sheriff’s office, paying them better salaries than their official law enforcement jobs did, but Tim was the one he called when he needed something done a certain way.

Tim, for his part, fashioned himself into the big man he fancied himself. He had always been athletic, but his interest morphed into an obsession with bodybuilding, which has little to do with true strength and agility and everything to do with the exaggerated appearance of those things. There’s no actual weightlifting in a bodybuilding competition. The winner is the person best able to show how well developed and refined their muscles are.

While working for Bill, Tim started a gym in town. As he got deeper into his bodybuilding career, and as his role as Bill’s go-to man grew, Tim mixed and matched different anabolic steroids under the dubious belief that doing so would increase their efficacy. He mixed an anabolic sold under the name Equipose, intended for horses, with Winstrol V, also intended for animals. Along with the anabolics, Tim injected a liquid vitamin B complex marked “not for human use.”

The concoction led to outbursts, including one incident in which he grabbed a fast food worker and pulled him by the shirt through the drive-thru window because his order was taking too long. Riding shotgun with Tim during the fast food incident was Bill’s 17-year-old daughter, Stephanie. Tim hired her at the gym as an aerobics instructor, and soon thereafter the two began sleeping together in spite of the fact that Tim was married. Stephanie was 17 at the time, and Tim was 33. (The age of consent in Missouri is 17.)

Bill was by all accounts sanguine, even supportive, of the dalliance between his daughter and his right-hand man. “I don’t have a problem,” Bill told Tim during a conversation recorded in his office. “Of all the things, go back when all this started with Stephanie. The only one who’s never discouraged you has been me. Right? I mean I told you, I love you like a son.”

Even though Tim was married with two children, Bill went around town calling Tim his future son-in-law.

In October of 1989, Patti found out about the affair and kicked Tim out of the house. Tim spiraled, and soon every facet of his life seemed to be falling apart: his business, his finances, his mental health, and his control over his own behavior. He told Bill he was depressed about not seeing his kids, that he thought his wife was turning his children against him.

There was no clear way for Tim to resolve all this. If he left Stephanie, he’d alienate Bill, not only losing his largesse but also possibly finding himself on the wrong end of Bill’s wrath. On the other hand, if he left his wife for Stephanie, the rift would only widen between him and his children.

Out of that dilemma came a plan.

Tim carried the five thousand dollars he’d withdrawn out of the bank and directly to his boss’s office. If he thought anything was off about the plan, or that there was more going on than he sensed, he didn’t betray any suspicion.

BILL PLACED the money in a safe deposit box.

After Tim left, Bill called his friend, Sheriff Buck Buerger. Just as he had told prosecutor William Johnson about his ongoing conversations with his protégé, he had also informed Buerger.

“Tim just shocked the pee out of me,” Bill said. “The silly son of a bitch wrote a check out of his checking account to pay somebody to do this. He’s going to do this whether we set him up or we don’t, you know?”

“I can’t believe it.”

“It’s them damn drugs.”

Bill then expressed reservations about having a heavy police presence during his coming confrontation with Tim.

“If we would try to grab a hold of him, with six or eight of us,” he said, “all we’d end up doing is–it would be a really bad thing. This wouldn’t be any harder if it was my son.”

“You’re doing it for him big boy,” Buerger replied.

“I’ll get him by surprise, and I’ll get the cops on him if I’ve got any problems,” Bill concluded.

After that phone call, Bill left the SSI office and found another friend, Medical Examiner Gordon Johnson (no relation to prosecutor William). Bill and Gordon were close. In fact, Bill had arranged for Gordon, one of Jefferson County’s few prominent Black citizens at the time, to get the job of chief medical examiner.

“Put this in your pocket,” Bill said, handing Gordon an envelope. “Inside is a key to a safety deposit box at Boatmen’s. The tapes of my conversations with Tim are in there.”

The two men exchanged looks.

“In case something happens to me,” Bill added before leaving.

Bill had now shared his plan and the accompanying evidence with the prosecutor, the Sheriff, and the medical examiner, all the primary officials responsible for prosecuting homicides. Satisfied, he paged Tim, asking him to meet at Bill’s well-appointed house in Seclusion Woods. From there, he said, they would drive to St. Louis together to deliver “the package” to the hitmen.

Several hours later, Bill called the medical examiner from his Seclusion Woods home, evidently distraught.

“I tried to talk but he wouldn’t listen!” Bill exclaimed. “I had to shoot him.”

“My god!” Gordon replied. “What do you want me to do?”

“Get out here right away.”

Gordon grabbed his coat and ran out to his car.

After hanging up with him, Bill called Sheriff Buerger. “It went real bad,” Bill said.

“What?”

“Buck, he’s dead.”

“Do what?”

“Well it’s real simple. He’s dead.”

“Oh shit. God damn. Oh boy.”

Gordon arrived at Bill’s house first, followed shortly by Buerger. When an ambulance arrived soon thereafter, Buerger and Johnson sent it away without the EMTs ever seeing the body.

In the garage, Tim lay in a pool of blood. He had been shot twice at close range with a shotgun. One of the shots was to the back of the head.

EIGHTY MILES TO THE SOUTH of Festus, at the Cape Girardeau County prosecutor’s office, Morley Swingle opened Tuesday’s newspaper and read a short article about a former police chief who shot his deputy.

That’s odd, Swingle thought. But he didn’t have much time to ponder the case. Swingle was young for an elected prosecutor, and Cape Girardeau had seen an unusual rash of homicides, keeping him and his office busy. Despite holding the elected position, Swingle, 34 at the time, had no intention of running for higher office. He loved trying cases–murder cases, in particular.

That afternoon his phone rang. It was the prosecuting attorney for Jefferson County, which includes Festus.

“Did you hear about that shooting up in our neck of the woods?” William Johnson asked.

Johnson worked with Bill when Bill had been police chief. “And [Bill] Pagano tried to donate to my campaign a few days before the shooting,” said Johnson. But Johnson worried about the appearance of a conflict of interest. Johnson had recused himself from the investigation, and he needed a special prosecutor.

“It’s clearly justified, self-defense,” Johnson said, assured. “It shouldn’t take much time.”

Should take about one day, Swingle thought.

Two days later, Swingle and his deputy investigator Karen Buchheit drove to Festus.

Though Swingle was technically Buchheit’s boss, their partnership was one of equals. Buchheit could argue with him as much as she wanted. His only rule was that she couldn’t take a swing at him.

In the car, she thought about telling him she was pregnant with her first child. She thought better of it. She’d only found out herself a few weeks ago.

Buchheit and Swingle sat down with the Jefferson County Sheriff Buerger. He’d been elected to his position seven times and was a close friend with Bill. His wife worked as a secretary in Bill’s private security business. He represented the good-ole-boy network of Festus. Before the meeting, Buerger had already told the press on several occasions that the shooting in Bill’s garage was justified and no prosecutor would ever file a charge.

Buchheit was the first one to notice a photo of the dead Tim on the table in Buerger’s office. The back of his head looked like an entry wound, not an exit wound.

“What kind of weapon was used?” Swingle asked

“A shotgun.”

“Where did the shot hit him?”

“He was shot twice. Once in the face. Once in the back of the head.” Never heard of a self-defense case where the victim is shot in the back of the head, Swingle thought.

What he thought would be an easy case of justifiable homicide was looking more like a convoluted criminal conspiracy.

Buerger reiterated to the out-of-town investigators that there was no way Bill was guilty of a crime.

“Just listen to the tapes,” Buerger said.

“The tapes?”

Buerger told Swingle there were hours of tapes of Tim talking in practical terms about hiring hitmen to kill his wife.

Swingle could hardly believe it. He immediately thought of Tim’s widow, Patti.

“This poor woman,” he said. “Her husband was planning on killing her, and then [was] killed himself.”

NEWSPAPERS from across the state sent their top crime reporters to Festus. Within a day, the state’s headlines read, Ex-Chief was Mentor for Man he Killed, Women Complicate Tim Case, Dead Former Deputy Known Steroid User, and Widow Listens to Murder Plot Tapes.

Almost immediately pressure was on for Swingle and Buchheit to provide some answers. The tapes were evidence of a crime. They just weren’t sure what crime that was.

“The tapes are a double-edged sword,” Swingle said to Buchheit. “Maybe [Bill’s] doing all that because he really does think he’d be putting his life at risk by confronting Tim. By putting all the tapes in a safe deposit box, one spin is that he really did think it would be his body lying in the garage and nobody around.”

“Another spin is that this is truly first-degree murder. He plotted all this in advance, and he knew he was going to give the fake story that he was trying to make an apprehension of Tim and had to kill him.”

Buchheit had her doubts about what Bill’s intention had been with the tapes. If he’d recorded everything, why hadn’t he recorded the botched arrest that led to the shooting?

Before they had time to review all the recorded conversations, Buchheit sat down with Patti at Patti’s mother’s apartment in Festus.

Patti had been a widow for only a few days. She sat there poised, steady and unemotional, her voice that of a person holding it together or of a person completely numb.

She thought she knew Tim better than anyone. They started dating their junior year of high school in Festus. She was a cheerleader and Tim a football player. Patti became pregnant, and one month before graduation, they got married. Two years later, he was working for Bill on the police force.

At first, Patti was grateful for the well-paying job and the support of the richest man in town. But after ten years, the deep friendship between the two men had devolved into mutual suspicion.

“He wanted to get away from him,” she said. “If Tim ever got away from Festus, he was going to write a book about Bill. People wouldn’t believe the things that he knew.”

Patti explained how the gym brought Tim closer to Bill than ever. Bill sabotaged the private financing Tim had secured to buy the business. At the last minute, Tim had to go to Bill for a loan.

To Patti, Tim began his affair with Stephanie “because he felt sorry for her like he feels sorry for all the Pagano children.”

She said Tim tried to call off the relationship at one point, but Bill grew furious. It was another way to keep Tim close.

Patti told Buchheit that a few months after she kicked him out of the house, Tim showed up unannounced at her work.

He told her, “I don’t want to divorce you, but if we are going to stay in Festus, I have to divorce you. I can’t go into the details. But Bill’s already told people I’m going to be his son-in-law.”

Patti said that she and her husband reconciled. He didn’t move back into the house, but he did start spending most nights there.

“Any time he heard a car come down the street–-we live on a dead-end street, very little traffic. But when there were cars he was always nervous,” Patti told Buchheit.

“Who was he afraid would see him?”

“[Bill] Pagano.”

Bill had totally inverted her husband’s world. He could drive around town freely with Stephanie, his mistress. He had to practice discretion when home with his wife. Tim went to Bill’s house on Christmas morning but couldn’t bring his wife and kids with him.

“Pagano wanted Tim to marry Stephanie,” she said. “And, you know, and that’s the other thing that’s so crazy. If Tim married Stephanie, then Pagano would be sure that Tim wouldn’t ever reveal any secrets. He’d be family.”

About half an hour into the interview, a detective in the room named Richard Harris paused before delicately broaching the fact that Tim talked in practical terms about killing Patti for hours, on tape.

“Have you been told by anyone or have you heard a rumor from anywhere, or has Tim ever made the statement that he wanted you dead?” Harris asked.

“No.”

“We have some recordings...” said Harris,.

“Uh-huh.”

“...Of conversations where Tim has attempted to make arrangements to have you killed.”

“Bull!” Patti said.

“Also, supposedly Tim withdrew $5,000 from an account and turned it over to Pagano.”

Patti conceded that at times her marriage to Tim had been contentious, and maybe in years past he might have even spoken about killing her.

Harris informed Patti that Tim had withdrawn the $5000 a little over a week ago.

“I don’t believe you,” Patti said. “This is a set up.”

It was a surreal circumstance in which a woman targeted by her husband in a murder-for-hire scheme was insisting that her husband had been forced to do so. To the investigators, it became clear that if they were going to get answers, they would need to pry them out of Bill Pagano himself.

BILL, MEANWHILE, was sticking to his story. In the hours after the shooting, he had sat with investigators, giving them a clear description of the events leading to the shooting.

Bill said that when Tim arrived at his house, he met him in the garage carrying a shotgun. He then told Tim there were no hitmen in St. Louis and that the entire murder plot had been a ruse. Bill said he then told Todd he was under arrest.

“I will never forget. He was standing near the front of the car, and before I had to tell him to put his hands on the car, he grabbed his head like something exploded in his head and he screamed, screamed ‘No! No!’” Bill said. “It was an unearthly kind of scream. It was a scream like a demon.”

Bill said he expected Tim to come at him, but instead his former protege went in the other direction. Bill realized that if Tim managed to get to the other side of the car, he would have effective cover, leaving Bill totally exposed. Bill yelled out, “Hold it!”

In response, Tim “did one of those spinning crouches, came down and when he came down, apparently, his arm caught in the antenna. That’s when he was going at the weapon. At this point I figured I was shot if he came back up with [the weapon].... I shot him. Shot him dead.”

The preliminary investigator conducting the interview knew Bill, and he didn’t press him on the “spinning crouch” story, but Bill hadn’t counted on the investigators from out of town.

AS BUCHHEIT AND SWINGLE interviewed more people around town, most were adamant Tim had in fact recruited people to kill his wife, including his lifting partners Frankie Perkins and Dennis Rozniak. But in the same breath, the light of suspicion would often swing back to Bill.

After Perkins gave his account to Swingle, they asked the 17-year-old if he had anything else he’d like to say.

“Besides I think Bill Pagano had him killed?” Perkins replied.

“That is your opinion why?”

“Because of his daughter. I’m sure it goes all the way back down to Stephanie,” Perkins said. “Tim was trying to gradually break it off with her,” said Perkins. He thought Stephanie wouldn’t allow the relationship to end. Perkins recounted one night after lifting when he and Tim walked out of the gym together. Stephanie ran towards them in the parking lot. She got in Tim’s face.

“I have something on you,” she yelled at Tim.

Perkins didn’t know what she had on him, but he was sure it had something to do with Tim’s death.

He added: “It’s either that or Bill was too afraid that someone knew something that had to do with him and Tim both. He didn’t want Tim to open his mouth. It’s one of those two.”

The following week, the St. Louis medical examiner Mary Case informed Swingle and Buchheit that the blood splatter pattern on Tim’s shirt indicated that the first shot had come to the back of Tim’s head, the second one was to his face.

The investigators requested a second interview with Bill.

“Let’s just pin him down on which one was first,” Swingle said. “And let’s pin him down on this spinning crouch business. What does he really mean?”

A corporal with the Missouri Highway Patrol took part in the interrogation.

“On your first shot were you aiming?” The corporal asked.

“I just snapped,” Bill said.

“How about the second shot?”

“Snapped again.”

Time was running out. They would need to get Bill to tell the truth, or at least hint at the truth, before the small-town kingpin put up enough walls to mire the investigation entirely. If handled meticulously, their questions could tempt Bill, encouraging him to depict himself as a hero and maybe reveal new details in the process.

“You mentioned a spinning crouch in the initial interview. Which way did Tim spin, right or left?”

“’Spinning crouch’ was not the term I was trying to say,” Bill started, then paused. He said that he had shot Tim as Tim was attempting to dive between the back of his car and the garage to take cover.

“At this point I figured I was shot if he came back up with the weapon,” Bill said, meaning that Tim would have cover but he, Bill, would be stuck out in the open.

Bill added that when he fired the first shot he couldn’t even see Tim because he’d ducked between the car and the garage door.

The investigators reacted nonchalantly, though they knew this detail made all the difference.

“His story was that Tim was running away from him, trying to get behind the car,” Swingle told me. “But then when you put the garage door down, you see there was only eight inches between the car’s bumper and the door of the garage. You wouldn’t be able to run behind there. I mean, it was just an impossibility.”

Swingle added: “If he could have come up with an explanation that was believably self-defense, he might have talked himself out of getting charged.”

Two Festus residents–a high schooler and a police officer–came forward to say they saw Bill and Tim arguing the day before the shooting. The two accounts were at odds with two men supposedly in cahoots.

Then there was this: a $1.5 million dollar “key executive” life insurance policy on Tim, payable to SSI to compensate the company in the event of the death of its vice president.

Swingle spent the weekend considering all this.

On Monday April 9, exactly two weeks after the shooting and the county sheriff statement that “no prosecutor” would charge Bill with a crime, Swingle charged William Pagano with murder.

THE CASE eventually wound its way through the usual contortions of the judicial system. Bill was convicted after a 21-day trial, the longest murder trial in state history at the time. The jury handed down a confusing verdict that held the killing was not justified but also not premeditated. After he was convicted, Bill stood smiling with his family around him.

He would never serve a sentence. Instead, he stalled the appeals process for three and a half years then killed himself on the day he was to be taken to prison.

Throughout the trial, Tim’s erratic behavior and his steroid use were topics of testimony by those taking the stand for the defense. An expert witness from Harvard testified that Tim’s outbursts and violence almost certainly stemmed from steroid abuse and that such overuse could cause him to pursue an outlandish plot. But the prosecution rebuked such claims. Eventually, the small-town football hero would emerge from the trial with a bleak legacy—the dark, unhinged local boy who sought guidance from all the wrong people.

The citizens of Festus would talk about the trial and the family’s fights over Bill’s estate for years to come. Rumors swirled around Bill’s businesses, which possibly included connections to the mafia. One other prominent rumor claimed that Bill had, at one point, instructed Tim to join a rival private security firm, infiltrate the company and eventually kill the competing CEO. Tim apparently claimed to people in town that Bill had done something similar once before. In the late 1980s, a man who ran a security firm killed himself under unusual circumstances. We’ll never know for certain the foundation and future plans for Bill’s empire, but we can be sure Tim knew some or all of those secrets that were buried with him and Bill.

Festus now has a new Sheriff, a new mayor. It’s boosters say the town has been cleaned of its good-ole-boys past.

In the months between his trial and his suicide, Bill was often seen dining out at the nicest restaurants in Festus and St. Louis. Though his fate was sealed, this was the Bill Pagano both his enemies and allies would most remember—a man ensconced in luxury and power, steamrolling his way to the top through personality, force of will and baroque plots. On one of these occasions, a society columnist saw him at a pricey Italian restaurant in St Louis amid the dappled lights of the chandeliers, leisurely cutting into a steak and smiling hungrily for the onlookers.

RYAN KRULL is a staff writer at the Riverfront Times, St. Louis’ alt-weekly. His journalism has appeared in The Atlantic, The Daily Beast, the Columbia Journalism Review, Bloomberg CityLab, and many other outlets. He is also an adjunct professor of Communication at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.