The Old West goes out with a bang in its last train robbery, leading a series of investigators down unexpected paths to a shocking conclusion.

Fairbank, Arizona

February 15, 1900

The sun had just set. Darkness surrounded the glow from the gaslights at the railway station in the town of Fairbank, Arizona. Located in Cochise County, the town owed its existence to the railroad. Fairbank was the closest rail stop to the more bustling Tombstone, less than 10 miles to the east. While Fairbank did not have many houses, the town boasted a one-room schoolhouse and a fancy hotel for the train passengers. A large building near the train station housed a restaurant and a general store.

That night a New Mexico & Arizona line train was expected from the city of Nogales, 60 miles farther down the line. Gold and coins from Mexico were often shipped north aboard this train.

A small crowd milled about on the platform, talking and laughing. People from the town liked to come down to the station when the trains came in to watch the big steam engine and taste the adventure and romance of the railroad.

A few onlookers were drunk. A cowboy lay sprawled up against the station building, apparently asleep. Another cowboy hung onto a support post to keep his balance, giggling and twirling around. A third sat on a bench, leaning up against a post. His hat had a blue feather in the brim. Two other inebriated cowboys, who were brothers, were arguing loudly close to the tracks north of the platform. They were half-heartedly shoving each other and arguing.

Sheriff Thomas Brodrick of nearby Santa Cruz County happened to be on the platform, waiting for a friend to arrive on the train. He noted the argument off to his right and ignored it, except to smile in amusement. It wasn’t his county, so it wasn’t his problem.

The train whistle was heard in the distance and soon the chugging sound of the engine could be heard.Within minutes, the whistle was loud enough for people to cover their ears. Moments later, the big locomotive was rolling into the light from the station. The two brothers off to the side of the platform stopped arguing and walked together toward the train as the engine pulled up beside them.

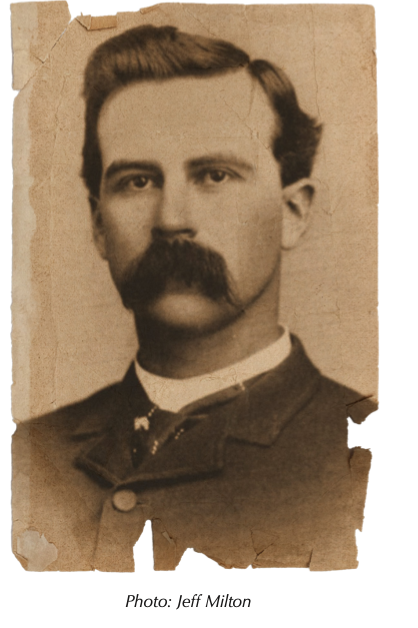

Unseen by them, inside the train, a man lounged against the door frame of the express car, where valuable cargo was kept, as the train came to a stop. Jeff Milton was the “express messenger,” the term for a guard who accompanied shipments of money.

Milton, 39, worked for Wells Fargo, the prominent Western bank. He was tall with short, dark hair and a Van Dyke beard, a popular style that was short and sharp. He was wearing a white shirt with a high, stiff collar that was unbuttoned with no tie. His fleece lined leather jacket hung open, exposing the fact that he had no gun on him. With the door opened, the Wells Fargo messenger was ready to start offloading the mail to the station manager.

The other three drunken cowboys on the platform suddenly seemed awake and sober as they regarded the express car guard. Expletives spoken softly shocked the people next to them. The three appeared somewhat hesitant, perhaps reconsidering their secret purpose.

But the brothers, closer to the train, were quickly aboard the steam engine with guns drawn. One of the cowboys on the platform fired at Milton, shattering the bone at the elbow of his left arm. He fell, leaving his revolver out of reach, but he still had a chance to defend himself; a loaded shotgun was propped against the door, a few feet away. The three cowboys still on the platform charged straight at the express car. Despite the excruciating pain in his left arm, Milton scrambled over to the shotgun, cocked it and fired into the belly of the bandit in front. The buckshot spread out from the gun muzzle, multiple pellets hitting the robber. The bandit behind the injured man had turned away at the sight of the shotgun, but one of the pellets hit him in the buttock.

Milton pulled himself up with blood running down his arm and pooling on the floor. Sweat poured off his face as he managed to close the car door. But he knew that the door would not hold them off for long. Pulling out the key to the safe, he looked around for a place to hide it. After a moment’s hesitation, he threw it against the wall of the railroad car, where it fell behind stacked boxes. Then he slid to the floor and lost consciousness.

The bandits, prying the door open again, found Milton in the pool of his blood, apparently dead or dying. While searching frantically for the key, they were joined by their comrades who had tied up the engineer and brakeman. There wasn’t much time. People were beginning to yell from the station.

After a few minutes of fruitless searching, they saw Sheriff Brodrick approaching with several other men. One of the cowboys grabbed a tin money box and they ran. Two others picked up one of their two wounded companions, whose nickname was Three Fingered Jack, and threw him on a horse. The five rode off into the dark.

They rode on in fear and anger and frustration, never to know that they had made the pages of history. Their attempt at riches was arguably the last train robbery in the Old West, a crime that would lead a series of investigators down unexpected paths to a shocking conclusion. As the new century dawned, along with it came the final gasps of the Wild West and the frontier spirit. Last chances for redemption would be harder to come by in the coming years and the slim line between hero and outlaw would be reduced to a vanishing point on the horizon.

Word of the robbery spread rapidly by rider and by telegraph. In Willcox, another whistle-stop town approximately 40 miles to the northeast, Cochise County Deputy Sheriff Burt Alvord sat in Schwertner’s Saloon drinking with friends. The son of a respected justice of the peace, Burt was a big man in his mid-30s, over six feet tall with a light brown mustache and not a hair on his scalp. He always wore a type of bowler hat with a wide brim, lying on the bar beside him. Someone burst in, yelling for the deputy.

Burt turned to look at the town’s telegraph operator, who was talking so fast no one could understand him. The deputy placed his hands on the man’s shoulders and calmed him down enough until the operator got the words out: The train had been robbed in Fairbank.

Horses were saddled. Saddlebags were packed with water and ammunition. Nearly 30 men were deputized, mostly from among the deputies’ friends, to form posses of searchers. In short order there was little left in the streets of Willcox except the settling dust and gossiping people.

Meanwhile, a telegram was sent to Deputy Billy Stiles, a friend of Burt’s, who had been nearly 100 miles away in Nogales. Billy was about 30 years old with short, curly brown hair, a small handlebar mustache and a gentle, almost cherubic face. He and wife, Maria, 30, had a 5-year-old and hoped for more children.

But Billy was out, and did not receive the telegram. He had planned that afternoon to meet with Wells Fargo messenger Jeff Milton to look at some mining property near Nogales. Milton was supposed to have the day off. But the assigned Wells Fargo messenger for the day had gotten sick and Milton had to cover his run on the New Mexico & Arizona line train. Milton forgot to contact Billy to cancel their plans.

Billy waited for a couple of hours, then gave up and headed back to Willcox. Riding on deer trails and wagon roads, through the desert, around mountains, over dry washes, past Fort Huachuca and on into Fairbank, he didn’t see another soul. As he rode into the town, he saw the crowd at the railroad station and found Burt Alvord and his posse already there. Burt told him about the train robbery and about Jeff Milton being shot. Billy tried to calm Burt down, but Burt stomped off, swearing to run down the bandits and bring every one of them to justice.

Burt had a taste of notoriety a couple years earlier. A cowboy from Mexico was tearing up a saloon, not long after the start of the Spanish-American War. The cowboy reportedly was yelling that he was going to “trash” the United States, saving Spain the trouble. In his role as deputy, Burt tried to arrest him, but the man swung at him and Burt shot him dead. The town applauded, though for the man holding the gun a wider range of emotions no doubt swirled after killing a complete stranger: exhilaration, regret, second-guessing.

The posse of searchers dispatched in the wake of the Fairbank robbery followed orders from the deputies to interview witnesses and railroad employees. Then they walked the tracks, looking for hoofprints. But most of the prints had been obliterated. Burt Alvord split his posse up into three groups. Billy Stiles took one group north. Another friend of Burt’s, an ill-tempered man named William Downing, led another party south. Burt led his group east toward the Dragoons and the Chiricahuas, mountain ranges that run parallel to each other on either side of Sulphur Springs Valley.

Finding the outlaws went beyond this one crime. The railroad was vital to the developing economy of the west. Transportation of resources, people and manufactured goods by railroad cut both costs and time substantially. Fast transit, especially for passengers, brought the world closer, unifying far flung villages into a loose local society where nearby towns became ‘we’ instead of ‘they.’ Crime against the railroad was a crime against the West.

The injured Wells Fargo guard, Jeff Milton, was known for his dedication to duty and honor. After the Fairbank robbery, as people all across the country prayed for his recovery, he became a symbol of heroism in the West, and this increased the urgency to catch the culprits.

The five Fairbank train robbers had vanished even as the story of their crime became a sensation in the county. The bandits, meanwhile, were still getting to know each other. They had never worked together before. “Bravo Juan” Yoas, with his hair tied back in a pony-tail at the nape of his neck, had been in the area for many years, moving back and forth from Mexico to Cochise County. Two of the other perpetrators, brothers George and Louis Owens, had arrived from Texas a few months before. They were squatters, having taken over a deserted cabin near Pearce, Arizona. “Three Fingered Jack” Dunlop, 28, had packed a lot of rough living into those years. Most recently he had been extradited from Colorado to Arizona on a warrant for horse theft. However, when he arrived in Cochise County, the plaintiff could not be found and he was released. The final thief, Bob Brown, had just arrived from Texas weeks before. All these men were probably in their late twenties or early thirties, by this point scruffy with week-old beards.

The five of them rode eastward toward the Dragoon Mountains. They were depressed and angry. George Owens had opened the moneybox from the train only to find it contained a grand total of $42, a value equal to approximately $1,400 today. Not enough to have put their lives and their freedom at risk. Furious it was not more, he had thrown it to the ground. His brother Louis sighed and dismounted, picking up the money. He gave each robber 10 dollars, except Jack, who was terribly wounded, barely hanging onto the neck of his horse. They could see that Jack wasn’t going to make it much farther, and money would be wasted on him. The last two dollars went into Louis’ own pocket.

Bravo Juan decided to head south to Mexico. He had continued to whine about his wound, so the others were happy to see him go. The Owens brothers wanted to go home to their cabin outside Pearce on the other side of the Dragoons. Bob Brown was left riding with the critically wounded Three Fingered Jack, who had been shot on the train in the abdomen by Milton.

As they rode, every step Jack’s horse took jarred his abdomen and the injured man groaned. Several miles later, Bob Brown and Jack were following a trail along the San Pedro River. Jack was slumped over his horse’s neck, whimpering softly. Finally he slid off the horse into a heap on the ground, crying out as he landed. Brown got off his own horse and looked at the dying man. He knelt beside him.

Brown knew there was nothing he could do for Jack. He got a bottle of whiskey out of his saddlebags and gave it to the wounded man to help with the pain. He may have patted Jack on the shoulder before he climbed on his horse and rode away.

The fugitives had been fortunate to have a head start while the county sheriff, Scott White, was away on business. Now they had to evade two perpetual underdogs who had never quite achieved as much as what they could dream, Deputies Burt Alvord and Billy Stiles. On the other hand, those unfulfilled dreams could well intensify the stakes and motivations for Burt and Billy to hunt them down. They had the chance to live up to the high standards exemplified by Sheriff White, Burt’s highly accomplished father, and the injured guard Jeff Milton. They also had a rare opportunity to redeem themselves after coming up short in a similar situation.

That earlier incident had occurred on September 11, 1899, a year prior to the Fairbank robbery. A Southern Pacific train was due at about 9 p.m. at Cochise Station, 10 miles southwest of Willcox and about 45 miles northeast of Fairbank. Cochise Station was just a dot on the map, a stop for the trains to drop off and pick up mail and the occasional passenger. Sometimes an ore car was added or cattle were driven onto a stock car.

As at Fairbank, there was always a small crowd at Cochise when the train came in, a chance for entertainment and camaraderie in a tiny town out in the desert. People stood around and chatted with their neighbors and waited for the shrill whistle that would announce the arrival of the train. And out in the desert a few miles from town, two bandits waited for the train.

When the train came from the east, it had to climb a steep grade that would slow it down. The bandits knew this. They also knew that the train was supposed to be carrying the payroll for the miners who worked relatively nearby at Pearce.

As the locomotive struggled up the hill toward Cochise, the engineer looked out and saw a red lantern swinging on the track ahead. Obeying the universal signal of danger ahead, the engineer slowed the train to a halt. Moments later he and the brakeman were looking down the barrels of two guns. The bandits were masked and did not say much.

They walked the engineer and brakeman back to the express car.

One of the bandits shouted, “Open up the door!”

The Wells Fargo messenger, or guard, a colleague of Jeff Milton, yelled back, “Go to hell!”

The bandit pulled several sticks of dynamite out of the saddlebag he was carrying, letting the engineer see them. “If you don’t open the door, I’m gonna blow up the whole car. I’ve got dynamite.”

The engineer shouted to the guard. “He’s got the dynamite. You better open up.”

There was silence for a minute, then the express car door slowly rolled open. The Wells Fargo guard stood in the opening with his hands above his head.

The two robbers positioned the dynamite at the safe and ignited it. “It blew the roof off the express car,” reported the Arizona Sentinel, “and cracked the massive safe into a hundred pieces.” They scored a fortune, with estimates as high as $30,000, an amount equivalent in today’s currency to nearly one million dollars. Newspapers would note that the two bandits were very polite, apologizing for taking jewelry and watches from the passengers. Then they rode off, marking an incredible success.

Once the bandits had galloped away, the train pulled into Cochise Station. A young man, just arrived from the East, had been hiding under his seat in a passenger car. In a reminder that the Old West could convince everyone they might be a hero-in-waiting, when the train stopped, the young man crawled out from under the seat, raced outside, and excitedly fired several bullets into the air with his revolver. The brakeman took his gun away and led him back to his seat.

Law enforcement hardly had more luck than that overeager newcomer. As Cochise County Deputy Sheriffs, Burt Alvord and Billy Stiles assisted county Sheriff Scott White in the attempt to find the bandits.

At first, newspaper reports reflected optimistic attitudes among the deputies about their prospects for making an arrest in the shocking dynamite-powered train robbery. Then the reporters noticed that as the posses were going farther out each day, with nothing to show for it, the morale of the lawmen faltered. The deputies kept up the searches for weeks until the sheriff, concluding it was a lost cause, told them to get back to their usual routines.

By some accounts, Burt as a teenager had witnessed the gun battle in Tombstone between Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and their adversaries at the O.K. Corral. If Burt and Billy had hoped to achieve the kind of fame and legends surrounding such law enforcement heroes of Arizona as the Earps, they had failed miserably so far.

As Billy and Burt continued to lead their search posses, reinforcements were dispersed to help track down the train robbers. A new posse was organized by Sheriff White, who had returned from his trip to Tucson. He was a tall, handsome man in his early 40s with curly brown hair and a walrus style mustache. His posse was larger and composed of men who were generally more responsible and professional than those in the deputies’ search teams. White’s posse consisted of a blacksmith, a farrier, two bankers, several ranchers and the Willcox town doctor, along with several clerks and mill workers.

After re-interviewing witnesses in Fairbank, the newly arrived investigators headed for the trail along the San Pedro River. Once there, they were able to follow the trail of the train robbers. A few miles down the path they found a blood trail. The blood spatters led off on a sidetrack and after a mile, they heard soft, agonized groaning. Three Fingered Jack was lying on his side, legs curled up, holding his belly. A cactus he had managed to light on fire for warmth was still burning, an eerie addition to the scene. He had passed out, only waking up when his clothes caught on fire from the cactus, burning part of his foot. The members of the posse gave him water and got him on a horse. Jack passed out.

The men in the sheriff’s posse were elated. Multiple posses often competed with each other when searching for evidence and suspects after a major crime. Sheriff White’s group had proven their worth by capturing one of the gang of robbers.

Sheriff White and his posse brought Three Fingered Jack back to Tombstone, tied to the horse. For a day or so he was in and out of consciousness. He was attended to by Dr. George Goodfellow, the town doctor of Tombstone. Goodfellow had come to Tombstone as a young physician and ended up with unparalleled experience with gunshot wounds. He wrote numerous articles about the cases he had treated and the innovative methods he used to repair the damage. Within a few years he became famous throughout the country, known as the ‘Gunshot Doctor.’

Goodfellow operated on the train’s fallen hero, Jeff Milton, repairing the shattered elbow to save his arm--and probably his life. More pressing, Goodfellow treated the critically injured train thief, trying to save one of the men currently being demonized by the press nationwide.

Burt Alvord had just returned to Willcox. His posse rode much of the night only to come back empty handed. Several of the men grumbled that nobody could find anything on a moonless night in the Dragoon Mountains. Another agreed, saying that they were lucky they had not lost any horses to broken legs. Burt ignored the complaints and walked into the sheriff’s office to write up his report. Some observers thought that Burt was unable to seize opportunities, especially when contrasted with White’s successful capture of Three Fingered Jack. Maybe Burt was a man who would never live up to his potential, and maybe his friend Billy Stiles would be mired in the same perpetual disappointment.

After an hour’s struggle drafting the demoralizing report at the office, Burt felt he had put enough words on the paper and went to his house in Pearce. His wife, Lola, 22, was out in her beloved gardens. She raised chickens and kept a vegetable and flower garden. No matter how much of her energy went into their home life, something was usually missing: Burt. Given his series of roles in law enforcement, he had rarely been home, even though his devotion to Lola was evident to observers. Now Burt sat down next to her on a stool and told her about his night. She listened intently, then told him to get some sleep.

Burt slept a good part of the day. That evening he went back to Schwertner’s Saloon to get the latest news over a drink.

William Downing, one of the members of the search posse Burt put together, was leaning against the bar, nursing a beer. Of medium height and lanky, he sported a handlebar mustache. He was 40 years old and arguably the most unpopular man in town. Downing was always in a bad mood and he tended to spread his bitterness around. But he liked and admired Burt.

Downing relayed that Sheriff White had found Three Fingered Jack in bad condition. Jack hadn’t talked to anybody since he was still unconscious. It seemed like a casual conversation, sharing the latest news and gossip, but anyone watching closely might have seen something else in the disagreeable Downing’s face--a suspicious glint that suggested dark secrets.

Morning came, and it was time for Burt to hand in his report on the case, however much this would seal his fate as a mediocre lawman. When he walked into the sheriff’s office, he found himself looking down the barrels of several guns. Three Wells Fargo detectives were waiting for him. They relieved him of his gun and his badge.

The bombshell allegation landed on the community with the power of a detonation: Burt and Billy had not merely been incompetent investigators of the robbery; they had been its masterminds.

Billy and Burt had not been seeking law enforcement immortality at all; they had used badges as a brilliant cover. Maybe there had been a time where they genuinely sought civic-minded accomplishments. They both had solid reputations as law enforcement officers. Billy was never as aggressive as Burt, who sometimes used his position of authority to settle personal scores. Probably the greed had been lurking there all along, and when hopes for glory fell apart, dreams of easy riches multiplied.

One night they found themselves leaning on a bar, talking about what they wanted for themselves and their families. All of it required money that they didn’t have and that they would never acquire as deputy sheriffs.

This dual life came to a crescendo with the sensational, dynamite-scorched Cochise train robbery, which had been seen as the first mark of Burt and Billy’s limitations as law officers. The reality was entirely different. On September 11, 1899, they were two of the four men playing a card game in the back room of a Willcox saloon. They made a lot of noise and frequently ordered drinks. Billy Stiles and a conspirator slipped out a window and rode for Cochise, about 10 miles away. Meanwhile, Burt Alvord and fellow Deputy William Downing, the town curmudgeon, continued to laugh loudly enough to be heard outside the back room. When the train came in from the east, the long uphill grade would slow it down. When the thieves signaled the engineer to bring the train to a halt, Billy hopped aboard with his gun drawn. The two masked bandits then forced the Wells Fargo messenger to open the express car, blew the safe with dynamite, collected some jewelry and watches from the passengers and rode like hell back to Willcox.

They climbed back in that window of the saloon before the telegraph officer came running in with the news of the train robbery. They were being called to catch the robbers.

Burt and Billy were hardly the first law enforcement officers to dabble in crime. Many of our legendary lawmen of the West had long arrest records. Even Wyatt Earp and his brothers, James and Morgan, had been arrested numerous times. Wyatt was arrested for murder once before being acquitted. Billy the Kid was deputized for a few weeks, pursuing murderers, before being deemed an outlaw himself. There was no clear distinction between the law and the outlaw in the Old West. There were good men and women on both sides. Darkness overlapped the light and people were sometimes forced into paths they may not have wanted.

Billy and Burt, however, concocted a unique and clever scheme that allowed them to perpetrate a crime and then be the ones to investigate it.

In the wake of their triumph, the gang of four were elated. Their first crime had gone off without a hitch. They made thousands of dollars. Greed was never sated; it growed and soon ruled their hearts. They thought it would be just the first in a long string of scores.

It seemed sensible, in planning the next heist, to try to create more of a buffer between them and a robbery. This time, on February 15, 1900, Burt and Billy sent five men they did not know well to rob a train. The inner circle who knew the truth suddenly grew from four to nine. They planned the robbery not a few miles outside the station but right in the train station itself with dozens of people around, after making sure expert gunfighter Jeff Milton was not scheduled to be on duty. But their hired hands were not wise enough to abort the plan when they spotted Milton.

The plan fell apart in and around the train, and started a chain reaction that led to the seriously wounded Three Fingered Jack improbably gaining consciousness while under the care of doctors.

Doctor Goodfellow put Jack in the old hotel he used as a hospital and did his best to make the man comfortable. Jack complained he was “deserted” by his companions and “left to die.” Jack felt betrayed, but he refused to name his co-conspirators for two days. Then Jack realized he was not going to recover. “I guess it’s all up this time,” he said in a weak voice when a reporter visited him. “I was treated pretty roughly,” he said of his gang. He made a full confession to Sheriff White.

The Tombstone Epitaph reported that the confession had broken the case wide open. “The posses were on a hot trail.”

Dominoes quickly fell. The Owens brothers were found at their cabin near Pearce. Bob Brown made it all the way back to Texas before he was caught and sent back. Bravo Juan Yoas reached Mexico, where the authorities, notified by telegraph to look for him, found him in Cananea and turned him over to Sheriff White.

But the shocking revelation by Three Fingered Jack had not been the names of the career criminals at Fairbank, but rather that Jack and the other four were hired guns. Jack had explained how the plan counted on Wells Fargo guard Jeff Milton not being on that train. Jack had also been able to name the mastermind of the robbery, the very same man who had seemed to be feverishly investigating it, the loudest and angriest leader of the posses: Burt Alvord. Sheriff White shared the intelligence with the other investigators, which resulted in warrants. After the Wells Fargo detectives quietly arrested the disgraced deputy, he was taken to a cell in the Tombstone jail along with his friend and member of his posse, William Downing, the grumpy rancher, accused in the same conspiracy.

Meanwhile, Billy Stiles had missed the dramatic arrests of his co-conspirators; he had been out riding all night with his posse. By early morning he had six exhausted men who wanted nothing more than to go home. On their way back, they had run into a man on the Charleston Road who told them about how the sheriff had found Three Fingered Jack and brought him into Tombstone. Billy sent his men off to find their beds and rode on alone.

He spent most of that day thinking and resting. Jack was alive and was going to talk, maybe already had. That meant they were all headed for prison. The next morning he rode into Tombstone to the sheriff’s office, dismounted, and tied up his horse. A deputy came out with his gun drawn. Billy put his hands up.

When Billy Stiles faced Sheriff White, he admitted everything, and agreed to testify to the authorities against all of his co-conspirators if he was spared jail. The opportunity was too good to pass up for law enforcement; Billy’s information could ensure Burt and the others involved would be locked away for a long time. There was an added benefit to the arrangement, too, of making Billy take responsibility and, in however minor a way, make amends for his descent into greed and crime.

In the crowded Tombstone jail, new prisoner Burt Alvord did not have to look far to see the disappointment so many people felt in him. The jailor, or warden, was a man named George Bravin, age 42, a friendly family man and former constable. Years before, Burt had worked for Bravin as a deputy constable in Pearce, Arizona. Burt and George had worked together as a team for those several months, effectively bringing law and order to that boomtown. Now Bravin had his former deputy behind bars.

Burt’s situation was far worse than that of Bravo Juan, one of their hired guns for the Fairbank robbery, who sat in the same jail. To have been a criminal who committed crimes was expected. But Burt’s imprisonment was a stunning fall from grace, a stain on their whole fraternity of law enforcement officers who had sworn to counter the lawlessness among cowboys. Burt was an embarrassment to everyone he had worked with and to Cochise County.

Burt’s shame had room to grow. On April 8, 1900, Billy Stiles, who had turned state’s evidence, stepped into the jail to visit. Some reports indicated that Billy actually had earned his way back into the trust of authorities so completely that he had been engaged to help guard the prisoners, his former co-conspirators.

The jail at Tombstone was originally a 20’ by 20’ wooden structure on 6th Street with a small office attached. The Cochise County Courthouse was built in 1882 when Tombstone was the county seat. The jail was moved into the rear portion of the courthouse a few years later.

Burt and Billy, friends and former partners, faced each other in a poignant tableau. Together they had encapsulated the often fluctuating roles of the Old West cowboy; their seamless movements over the last year between law and crime and back again had been singular. In masterminding arguably the last train robbery, they had unwittingly helped mark the end of that era, shedding light on society’s need to take the distinctions far more seriously. Now, separated by iron bars, they could be said to represent two very compromised versions of the cowboy. Burt was the disgraced cowboy who ultimately failed both as lawkeeper and criminal mastermind; Billy was a rehabilitated citizen tainted by misdeeds.

In Billy having avoided Burt’s dismal fate of turning in his badge for prison stripes, the rule of law seemed to have won the day convincingly. With the new century of 1900, a new era of peace seemed to be ushered in. The very trains that they had disrupted in their robbery plots had also contributed to a sea change; with the continued expansion and sophistication of the railroad, civilization crept through the West.

But at the same time, it was hard to shake the appeal of the wildness in the Wild West, to surrender the myth of a freedom that skirted all rules and codes. After locking eyes with Burt, Billy reached under his jacket and pulled out a gun. He turned around to face George Bravin, demanding he open the cells.

When the shocked Bravin refused, Billy shot the jailor in the foot, shooting off two toes. Securing the keys, Billy released Burt and the rest of the prisoners, 25 in all. Prisoners stepped out of the cells and milled around, unsure what to do. Bravin, despite his bloody injury, pleaded with the prisoners not to forfeit their chances in courts and for their futures by walking out the door. One by one, most of them returned to their cells. Even Downing, one of Burt’s men who had been part of both the Cochise and Fairbank robberies, decided to remain in jail. In fact, every prisoner returned to the cell except Burt and Bravo Juan.

Burt and Billy had thrown down the gauntlet. They could guess the familiar cycle that would certainly play out once again, one with warrants and posses and rewards.

With Bravo Juan in tow, Burt and Billy prepared to escape and face possible immediate opposition in the streets of Tombstone, where everyone was armed and furious with them. If the rest of the prisoners in that jail had accepted the end of lawlessness, the escapees were bucking the system, betting that the Old West as they had experienced it was still alive and well, a place where transgressions could be wiped clean, a realm in which anyone could be reinvented. They were betting they could disappear back into it. At least for the time being, they did just that.

Bravo Juan’s fate remains uncertain. He was known to be in Sonora for a few years. A brief note in The Tombstone News in 1908 said that he died “down on the Amazon River.”

Nine days after his explosive confession, Three Fingered Jack had died from his injuries, becoming the last man buried in the Boothill graveyard in Tombstone, yet another marker of a vanishing world.

Sheriff Scott White served three terms as sheriff of Cochise County. He was a legislator, a county supervisor, a deputy United States marshal and he was credited with being one of the finest lawmen in the territory. He also served as warden of a state prison and was an instigator for prison reform. When he died in 1936, he lay in state in the capitol rotunda in Phoenix and flags were lowered to half-mast all across the state.

Billy and Burt’s lives seemed to play out in a repeating loop. They would continue to alternate between criminal and legitimate enterprises, sometimes together, sometimes apart. Records about their families remain inconclusive, though Lola divorced Billy in September of 1900, seven months after their last train robbery. She disappeared into a life far away from the violence and killing that had surrounded Burt Alvord. Billy would eventually happily settle into a role as a lawman under an alias in Nevada, his wife Maria remaining with him. This later chapter in his life, when he apparently never deviated from his oath to the law, ended with Billy shot and killed while serving a warrant. The ultimate fate awaiting Burt would serve him perhaps the cruelest cut: anonymity and normalcy. He would work in construction for a couple of years in Panama and Brazil before dying of yellow fever, leaving behind a net worth of $800, approximately $23,000 in today’s values.

Fairbank, Arizona was gradually abandoned when its railroad stop became unnecessary, turning it into a ghost town. A vestige of Burt and Billy’s Old West may well remain today, as tales persist that some of the spoils of their first train robbery remains hidden somewhere in Cochise County.

A week after he witnessed the jailbreak in Tombstone, George Bravin was back at work in the jail, his foot in a cast, propped up on the desk. A Mexican man entered and returned the keys to the cells to Bravin, along with a note with just one line.

“Tell the boys that we are all well and eating regular.”

RHEMA SAYERS is a retired physician who began writing as a second career. She lives in the Arizona desert.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.