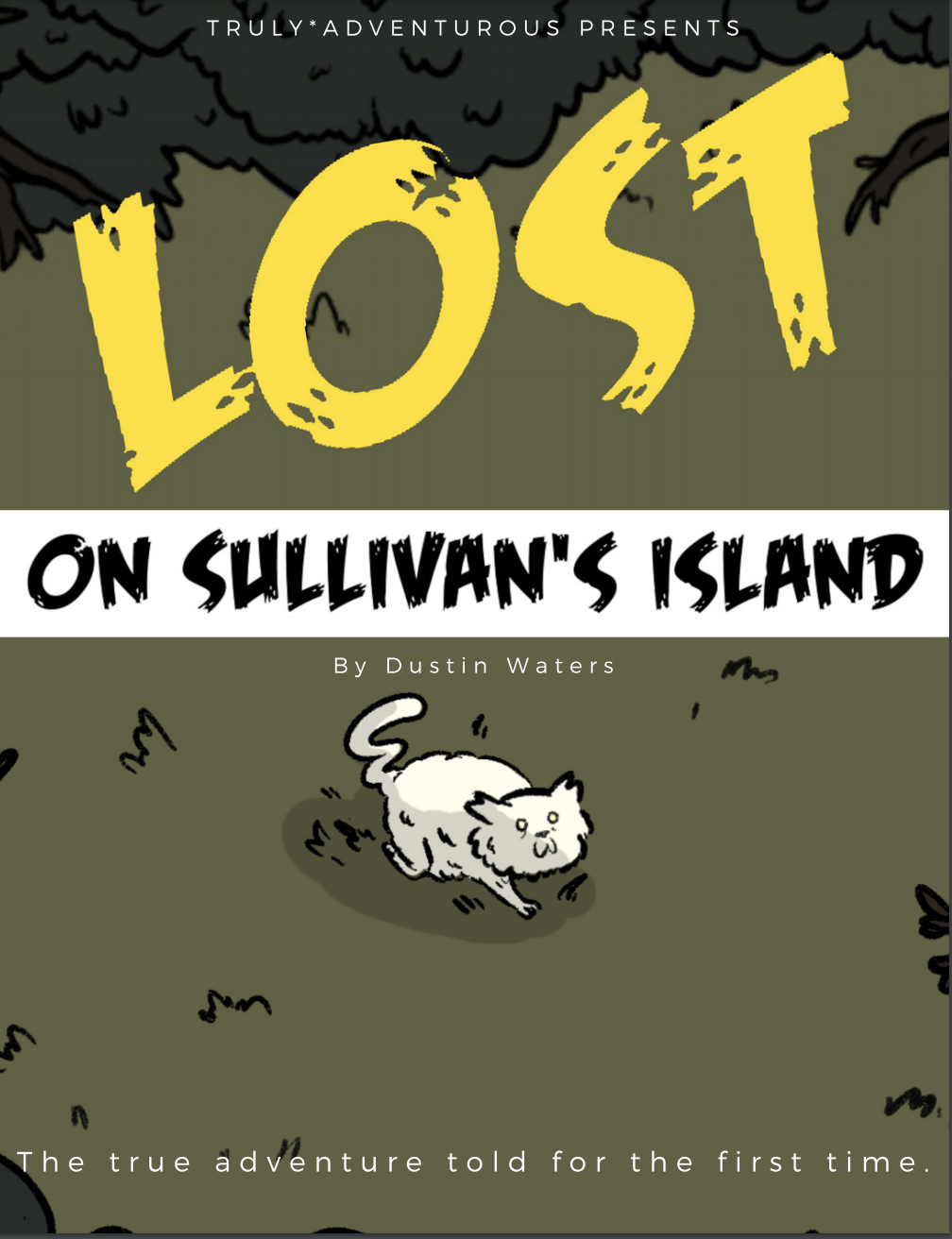

By Dustin Waters

When a multimillionaire offers a massive reward for her missing cat, searchers race each other across a ritzy island filled with mysteries

The small Doll Face Persian wriggled from its owner’s arms on February 1, 2019, in a panic into a thicket of live oaks, dense red cedars, and the iconic palmettos that grace the island town’s seal. Scurrying through the needle grass, this was the cat’s first time out of the house.

Generations of selective inbreeding and constant pampering had left this timid feline more suited to daily grooming by her owners than survival in the outdoors. Perfectly manicured with a bright white lion cut, looking like some hybrid of show poodle and bonsai tree, this house cat was less “king of the jungle” and more the newest potential prey on Sullivan’s Island. The Doll Face variety of Persian cats carries the equally humiliating breed nickname of “teacup.”

Her flight had begun out of fear and now for the first time, this pedigreed pet with translucent green eyes and white fluff styled around her cheeks and paws had crossed the threshold into the untamed world. A threshold that represented the age-old struggle between human- and feline-kind alike, the tug of war between comfort and freedom, between routine and excitement, the known and the unknown. What was out there, and who?

Tan-faced and welcoming with hair that’s more salt than pepper, Andy Benke had by this point handled the day-to-day operations of the small South Carolina town of Sullivan’s Island for 16 years. The genial, unassuming town official keeps Robert’s Rules of Order FOR DUMMIES on the bookshelf in his office.

Sixteen years. Sixteen hurricane seasons with countless storms that ravage the coast. Sixteen summers where the island of around 2,000 residents more than triples in population as beachgoers flood its streets and beaches. And 16 summers waiting for the next new problem to meet his shores.

The four-mile-long barrier island sits on the north end of Charleston Harbor. On one side, a lush marsh and the Intracoastal Waterway separate this narrow strip from the mainland. To the other side is nothing but sea.

Lowcountry natives have a special designation for those who choose to relocate to South Carolina’s coast. They are deemed “from off” — an outsider’s mark that is hard to shrug. Sullivan’s Island has a long history of drawing a clear line between those who live there and those passing through. No hotels, motels or bed-and-breakfasts. Even at the time of its incorporation in 1817, shacks and lean-tos were forbidden. To be considered a part of the community, one needed to have put down roots in a significant way. And any outside force encroaching on Sullivan’s was sure to draw a spirited response.

On this particular day in early February 2019, things appeared calm on the island. Far from the height of beach season and the hectic summer months, Sullivan’s had once again returned to the sleepy coastal community that attracted its elite residents in the first place. Stepping out of the island’s only gas station, Benke noticed a flyer hanging on the wall. After an initial glance, he did a double take. Something seemed off. Benke, tasked with being the watchful eye for his community, looked again.

Across the top of the page in large bold type, the flyer read “MISSING” along with a pixelated photo of a small, stark-white cat named Vail.

This was not unusual. House cats get out, get lost, and usually don’t get found. Benke’s confusion over this particular flyer stemmed from what’s printed just below the photo of the 5-pound Doll Face Persian: “$10,000 REWARD for Vail’s safe return home.”

Ten thousand dollars.

Benke thought that they must have added an extra zero by mistake. Most of those who live on the island are no strangers to wealth, but whose first reaction to their missing cat is to put a $10,000 bounty on its return? To understand the answer to that question, you have to insert earplugs and step inside the quaking Victory Lane at Daytona International Speedway, back to the year 1993.

Rookie driver Jeff Gordon has just won the first of two Twin 125 qualifying races for the Daytona 500. Years away from becoming a dominating force in motorsports — and being resented just as much as he was adored — Gordon is just a kid with a bashful smile who loves to race.

Starting out at the age of five, Gordon earned a national title by the time he was eight. His family eventually moved from the West Coast to Indiana after learning that Gordon was legally prohibited from racing at the age of 13 in his home state of California. Finally in 1993, Gordon claimed victory on a much grander stage. But this win plays a more significant role in his life than the boyish 21 year old could have imagined.

Waiting in Victory Lane to celebrate his win, Gordon is greeted by that year’s Miss Winston, an aspiring teacher in her early twenties named Brooke Sealey. As a student at the University of North Carolina in Charlotte, Sealey was majoring in early education when she realized she could make some extra cash modeling. She answered an ad, and an agency suggested that Sealey might fit the role of a Winston Cup model. She knew nothing about professional racing, but this was just intended to be temporary work while Sealey finished school.

Gordon caught Sealey’s attention that day in Victory Lane and scored a date. For the first few months of their relationship, the fledgling couple was forced to keep their relationship secret because of a stipulation forbidding Winston models from dating drivers. Once Sealey’s contract expired, the two went public with their relationship. They were married in North Carolina on November 26, 1994.

For the early years of their marriage — while Jeff and Brooke became the “Ken and Barbie of NASCAR” or the “king and queen of NASCAR” depending on the media’s mood for metaphors — Jeff’s victories and money piled up. Brooke responded to the rapid fame: “I’m just an everyday person.” A year later Jeff and Brooke discussed their personal lives together with a reporter for the South Florida Sun Sentinel, again explaining that despite the sudden wealth and celebrity that surrounded the couple, they were still “normal people.” Asked about the last big gift Jeff had splurged on for his wife, he mentioned the couple’s recent vacation to Puerto Rico.

“Well, there was the airplane,” Brooke interjected. Yes, Jeff had forgotten to mention his recent purchase of a Learjet. They were riding high with no end of the winning streak in sight.

Then things fell apart. In 2002, Brooke filed for divorce. This was around the same time Jeff’s professional dominance also came to an end, with the driver failing to finish in the top five of any races that season. Still, a court affidavit placed Jeff’s net worth at the time around $48.8 million, with the 31-year-old driver’s monthly income just over $1 million. For Brooke and her attorneys, this number seemed a little low. So much so that they attempted to subpoena Jeff’s fellow drivers at the same track where Brooke and Jeff had first met ten years prior. NASCAR officials went so far as to bar local sheriff’s deputies from serving legal papers to anyone at the track.

In the end, they avoided a courtroom showdown. Brooke waived requests for alimony, while receiving at least $15.3 million from the sale of two properties. In 2010, Brooke moved to South Carolina — a decision that would force her back into the courtroom. Prior to relocating, Brooke became a mother through an on-again, off-again relationship with a Bank of America employee who operated a pumpkin patch on the side. This child custody case threw back the curtain on Brooke’s lifestyle. Under examination, Brooke reluctantly divulged her net worth at the time of the March 15, 2011 hearing to be around $40 million.

That same hearing also offered up a memorable courtroom exchange between the opposing attorneys.

Opposing attorney: And the last job you actually had was when you were in college and you were the Mrs. Winston Cup?

Brooke: Yes.

Brooke’s attorney: Miss. Miss Winston. It wasn’t Mrs. Winston.

Judge: The what?

Opposing attorney: Miss Winston.

By this point, the former Miss Winston Cup seemed ready to remove herself from the spotlight permanently. The table was set for a lavish homelife on Sullivan’s Island for Brooke, her child, and her cat Vail. That was all until the day the carbon monoxide alarm had been accidentally set off, which also triggered the home’s general alarm system, and Brooke scooped up Vail into her arms and rushed outside. The yard filled up with emergency vehicles including a fire truck. When a police cruiser seemed to come out of nowhere, lights flashing, Vail spooked, leaping from her arms and disappearing.

Brooke, friends, and family, scoured the island until the sun went down. “She is a very sweet cat who we love dearly,” the family said. But what Sullivan’s Island lacks in size, it makes up for in vegetation — providing plenty of hiding spots for lost cats and predators alike.

Knowing this, Brooke and her team chose to enlist no half measures. As was made clear by that flyer they were busy posting that would stop Andy Benke and so many others in their tracks:

MISSING

$10,000 Reward

For Vail’s safe return home

5lb Dollface Persian with a lioncut

Please contact Lindsey with any information

The “Lindsey” listed was a local real estate agent and relative of Brooke Gordon, who apparently served as a buffer between anyone eager enough to pursue the reward and Gordon’s notoriety and assumed fortune.

Still, the wealth on the island that allowed for such a large reward in the first place also served to negatively affect the number of people willing to crawl through the island’s thick maritime forest.

“Most people out here, and it sounds crazy, wouldn’t put out the effort for that kind of money,” Lynn Pierotti, publisher of the Island Eye News, tells me. “Even though it’s a shitload of money.”

As the saying goes, one man’s shitload is another man’s dividend. But if most local adults were unwilling to bother over a mere ten grand or unwilling to encroach upon the property of island residents, kids were a different story. Kids are always a different story. During the tired days of late winter, this was a distraction.

“Kids all weekend were searching high and low for that cat,” says town administrator Benke. “My son, a senior, skipped school to go looking that Friday. Kids were out everywhere hoping for that reward.”

Vail had lived with Brooke for two years and, not coincidentally, was now two years old. Doll Face Persians are coveted pets, distinctive for their long fur and short stature. This breed is often described as gentle and peaceful. A timid demeanor perfectly suited for domestic tranquility.

Vail’s first introduction to nature was an odd intersection of coastal shrubbery and man-made paths. Cutting through the brush toward the sea at an area known as Station 19, the house cat would have found the dunes that separate home from the sea. Station 19 is really nothing more than a sandy path that leads to the beach. The only parking available is for golf carts. This is clearly outlined in the signage that designates various warnings along Station 19.

No lifeguards are on duty. Alcohol is prohibited. And coyotes are in the area. “They are smart, fast, and will take what they can get,” visitors of Station 19 are warned. “All pets must be kept in direct control. For your safety and the safety of the animals, keep them at a distance and never feed coyotes!”

The open paths that lead to the beach would be easier for a pet to traverse, but that leaves any small animals exposed to predators hiding in the brush. While Persians’ quiet natures might lessen any instinct to confront a wild animal, their tendency to be poor jumpers and climbers means that evasion is not a strong suit. With all of this to navigate, Vail’s greatest dangers were still to come if she could make it to nightfall, because of three terrifying words: coyote mating season.

The island’s coyote population was notorious for snatching small pets. For years it developed into a major bone of contention, with some residents calling for town officials to wipe out the coyotes by any means necessary.

Around the time Brooke Gordon closed on one of the ritziest homes of all the ritzy homes on Sullivan’s Island in 2013, residents also began to realize the presence of the invading coyote population.

In a letter to local Island Eye News on August 23, 2013, a longtime island resident reported that her cat, Duke, had gone missing, only to later be found in pieces in a nearby vacant lot.

“After putting all the clues together, I have concluded he was taken from under our house at night by a coyote, then killed and eaten in the tall grass across the street. I want to get the story out so that people are aware they are here and hungry,” wrote Gigi Runyon. “I would like to highly recommend that everyone bring their animals in at night and secure their trash so that the coyotes won’t have a food supply and will move on to other territories. I will have to live with my ignorance, but hopefully no one else will.”

This marked the beginning of a rising wave of panic that would weigh upon the community for years to come.

By the end of January 2014, middle school students began presenting class assignments on coyote control to members of town council. Meanwhile, more residents began to speak out about the encroaching coyote population.

By the end of 2014, the town’s Public Safety Committee presented residents with a coyote management plan, in hopes of assuaging fears. Town police would monitor and record any reported sightings, but proactive lethal measures would be reserved until an aggressive display involving a human occurred.

At the time, island resident George Malanos stood before town leaders and expressed concern that his four grandsons—between the ages of seven months and seven years —would become prey after the coyotes depleted the local rabbit population. Malanos said he felt like a prisoner in his own home on an island where the median household income ($120,850) is more than twice the national average.

Island resident Natalie Bluestein called on town officials to change the local ordinance to allow for seven-foot-tall fencing in order to protect her Springer Spaniel, which she believed was being stalked by the coyotes at the time.

The addition of leg traps and predatory wolves to the island was briefly discussed by residents and town council members as possible coyote deterrents, but concerns over the safety of small children were soon raised. Erring on the side of caution, town leaders decided that introducing wolves to address the coyote problem might be a slight overstep.

In February 2015, Jay Butfiloski, a coyote expert with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, was called by Sullivan’s Island officials to address the public’s concerns. In a packed trailer that served as Sullivan’s temporary town hall at the time, the mild-mannered, personable wildlife expert delivered the unfortunate news: Eradication of all coyotes would not be attainable, and coyotes will continue to come to the island.

“The best way to deal with them, at least in my opinion, is to deal with problems as they arise. The other option is to constantly be at war with them,” says Butfiloski. “And again, even that might not prevent somebody’s pet from being attacked. Sullivan’s also has the struggle during the summer and other times of year of dealing with the visitor population because they don’t behave, perhaps, the same way the residents do. It’s a vacation. It’s a party.”

The residents in attendance proposed the installation of seven-foot-tall electric fences lined with barbed wire as an appropriate countermeasure for their beachside community. With reports of missing cats fresh on their minds, these residents were willing to sacrifice the island’s welcoming atmosphere.

“If we were in a rural part of the county, a coyote’s not gonna hang around a bunch of people because they’ll get shot at. It does become a little more difficult in suburban areas because for legal issues, you can’t just pull out a gun and start taking crack shots at it, like you might do if you were on a farm,” says Butfiloski. “Typically, coyotes don’t hang around on a farm where they are seen a lot because those end up dead. In these developed areas, especially where there are a lot of people, it becomes more of a challenge to keep them afraid of people.”

In the following years, little changed around the island. Slow progress was made in the construction of the new town hall. Small pets continued to disappear from yards sporadically. The number of reported coyote sightings dipped and rose with the seasons, yet concerns remained. The same could be said for the human population visiting the island.

Since the early 1970s, the population of the neighboring community on the mainland of Mount Pleasant had grown from 6,200 to more than 68,000. Meanwhile Sullivan’s Island had only added 400 new residents. Islanders feared that their streets, designed and installed in the late 1940s to accommodate post-World War II traffic demands, would soon be unable to accommodate the heavy influx of more than 4,000 visitors who came to the island during peak beach season. Though curbing all public access to beaches proved a legal quandary, there had already been attempts to dissuade the daytrippers by restricting parking to one side of the street, cutting the number of spots almost in half, and by trying out “No Parking on Pavement” signs, which baffled visitors by requiring all four tires to be off the street, which would put their vehicles on private property.

The Sullivan’s Island Planning Commission, already wrestling with the coyote issue, was also tasked with managing the massive influx of partygoers expected for St. Patrick’s Day and the annual New Year’s Day Polar Bear Plunge. Rowdy crowds in 2013 had assaulted a police officer. Malanos compared the perceived threat of a coyote attack with that dreaded invading force of partygoers. Speaking to town council members, island resident Pat Votava also conflated the island’s coyote and tourist concerns, voicing appreciation, according to meeting minutes, for the “discussion of animal control… for both agenda items (coyotes and Polar Bear Swim).”

Then came February 2019, when all the wealth and attention and natural challenges facing the island collided with a missing house cat and a $10,000 reward.

News of the reward had been picked up by local media outlets and spread quickly across social media, including communities a stone’s throw away that had already plagued Sullivan’s gatekeepers. “10K? For a cat?” was the reaction of a young woman named Melissa. “Let me start searching!”

“Time to collect!” exclaimed Donald of Summerville, South Carolina. The first thought of Joe Jukofsky of Charlotte, North Carolina, was to camp out. Nate, another local, announced: “Goodbye 9-to-5, hello rich Sullivan’s Island housewife cat retrieval business.”

Of course, actually traipsing through the island’s maritime forest and private properties posed a variety of risks. The untamed nature of Sullivan’s forest areas was inhospitable enough, but invading the thickets that wind through various blocks of private property was a different challenge.

If islanders weren’t already sensitive about encroaching visitors, the prospect of a $10,000 prize luring desperate mainlanders to their home would do the trick. The notion conjured images of weekend warrior shark fishermen descending in droves on Amity Island in Jaws, or the motley crew of bumbling treasure hunters colliding in Mad, Mad, Mad World. The riff-raff, as they were viewed by some locals, seemed to feel the reward flyers gave them diplomatic immunity to trudge through people’s garages and yards, lugging coolers and water bottles with bendy sippy straws that may or may not have contained water. Some wielded butterfly nets with cans of tuna. As darkness fell, some had come prepared with night vision goggles.

Life on an island already means you’re caged in to some extent. Depending on the size of your community, it only takes so much before the scale tips in favor of those “from off.”

Friday night turned into Saturday morning, and Vail’s journey could not have come at a less auspicious time. On top of the challenges for even the savviest house cat among coyotes, here was a pampered pet showing up in the wild just as coyote mating season made these predators more protective of their own. And more aggressive. Chances of survival were becoming grimmer by the minute.

When a coyote attacks another animal in the wild, it’s not always a matter of food. Sometimes it’s just a matter of aggression or protecting their young.

Coyote populations in more suburban environments tend to grow more comfortable and therefore bolder as time goes on. Given enough time in developed areas, coyotes become less afraid of interacting with whatever might come their way.

During the daytime on Sullivan’s, coyotes are more likely to stick to thick cover, huddled under the cedars, palmettoes, and high grass that distinguishes the island’s homes from its more undomesticated terrain. It’s at night when the island’s coyotes are bold enough to step out into open areas and hunt.

With female coyotes in heat during mating season, male coyotes were likely to lash out at one another in the spirit of competition. These were the circumstances in which Vail found herself alone in the wild.

Recently—and no, this isn’t science fiction—coyotes around the country have been reported to be mutating into ever fiercer forms. In Northern California, a coyote with icy blue eyes was caught on camera. In the Northeast, human efforts to depopulate wolves forced the diminished wolf population to mate with coyotes in an effort to ensure survival. The result was a larger type of canine compared to your garden variety coyote. These new specimens were quickly labeled as coywolves. Meanwhile, an Alabama hunter shot and killed a 60-pound coyote, more than twice the typical size.

A coyote can tear out from a nearby thicket to snatch up a vulnerable animal in a walking path or it can confront a wayward pet with more trepidation. In this case, the behavior of the smaller animal may well dictate the outcome.

Asked about the likelihood of Vail evading Sullivan Island’s coyote population, the expert Butfiloski says it depends on the cat.

“Obviously the advantage a cat has is that it can climb. It could hang out in a tree and avoid all that mess,” he says, but warns that a cat familiar with canines in their home wouldn’t fare well. “That cat may be thinking ‘This is another dog. I’m gonna smack it on the face and it will run off.’ Well, it’s going to get a different reaction when a coyote comes up to it. It might try to smack it on its face but the coyote’s not gonna give up. In a case like that, the cat who is sort of naive to wild animals could be easily killed.” A nearby resident following the case named Holly feared the worst for Vail. “I thought with her coloring that a coyote had gotten her for sure,” she posted on a message board about the case.

Not far from Vail’s temporary refuge near Station 19 is the island’s Edgar Allan Poe Library. Connie Darling, an employee at the library, remarks: “I’ll tell you one thing: some of these people have these expensive Persian cats. And they think a lot of them.”

Despite differing opinions on the dollar value of a pet, there was no arguing about Vail’s worth. For the groups of kids searching the island, the cat was their chance at $10,000. Chasing the cat and the money involved sneaking through their neighbors’ yards and the black needle rush grass that populates the sandy soil, providing ample cover for any wildlife.

Another hidden risk was any well-informed opportunists who may have learned of the missing pet’s true owner. Though kept out of the headlines, the revelation that Brooke Gordon, commonly referred to in the area with the somewhat long-winded nickname of “Jeff Gordon’s ex-wife,” was offering such a hefty reward for the safe return of her family pet would potentially lead to some unsavory individuals looking to negotiate a higher payday should they discover the cat first. A reward could become a ransom. Whether you were hoping for the safe return of a beloved pet, a treasure hunt to split between your friends or the haul of a lifetime, the clock was ticking on all searches.

Harkening back to George Malanos’ fears of local kids falling prey to ferocious packs of coyotes, those groups competing in search of Vail found themselves starting from the island’s well-tread sandy paths that provide a clear path to the waterfront. Boisterous newcomers could also put the skittish coyotes on alert, pushing them further into the fields and woods where Vail could be hiding. The more reckless searchers leaving food around to attract Vail could also be inadvertently luring her predators. This would put Vail in ever more danger, as well as the kids themselves.

With the weekend upon them, the kids had free rein to plot their course in the search. As they explored the wilds of their home, the kids became better acquainted with a version of the island before it was tamed, when long-held superstitions and lore still hung as thick as marshgrass.

The legacy of Edgar Allan Poe, who was stationed on the island when he was in the Army, still hangs heavy on the town. He was said to have had a tragic romance here that inspired his poem “Annabel Lee,” and his ghost over the years had been spotted wandering and, as Poe’s ghost tended to do, writing poetry. Among the numerous local landmarks that allude to Poe’s legacy, there are the local library and Poe’s Tavern. The latter papers its bathroom walls with pages of Poe’s stories.

This includes Poe’s “The Black Cat,” which told the story of a troubled alcoholic driven mad by the murder of his beloved pet. Drunkenly lashing out at his pet, the unreliable narrator is continuously haunted following the death of his prized pet, Pluto. Despite discovering a potential replacement, the narrator manages to manifest his own ruin.

Clearly drawing inspiration from his own life, Poe was an alcoholic and noted cat lover whose tortoiseshell pet named Catterina is rumored to have perched on his shoulder as he wrote.

Even before Poe and coyotes made their respective marks on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina’s folklore often sought to predict and prevent the possible challenges presented by felines. One superstition insisted that the best way to prevent a cat from running away was to to butter its paws. In this case, the pet would remain in its new home to lick its paws clean.

A much more severe and supernatural superstition recommended cutting off the last joint of a cat’s tail to ensure that it remains at its new home.

Creepier still than a specter of Poe was the local tale of the pelican of Fort Moultrie, the same Army base where Poe had been stationed. The legend had to do with the Seminole leader Osceola. The Seminole’s name meant “black drink crier” because of the black tea he imbibed to prepare for war. When Osceola was being forcibly transported in 1838, he fell ill and died at Fort Moultrie. The doctor decided to decapitate Osceola and embalm his head to be examined.

The haunted pelican was said to possess Osceola’s spirit, spilling black liquid from his beak in search of the location of the headless body.

Beneath the same fort, there are those that are convinced an ancient treasure is buried in an ornate casque or box —well, ancient to kids, as it was buried in 1982 —that holds a key that opens a deposit box in a bank holding a precious gem. (Though the gem, reportedly, is only worth a tenth of the reward for Vail.) The Poe story “The Gold Bug,” too, includes a secret cypher that could lead to a hidden treasure on Sullivan’s Island. Depending on the tide, a massive WWII gun turret, sometimes rises up from the sand once every forty years or so, with rumors that other concrete military installations remain buried under another beachfront house. On Sullivan’s Island, it often felt some mystery was always under the surface awaiting discovery.

Then there were the other strange sights that could crop up around the island. Its isolated position lured military contractors to test sensitive equipment there, such as the giant amphibious vehicle developed by the General Dynamics Land System's’ Force Protection that had shocked residents when it roared across the beach a few years earlier. (Not far from that shore is a different kind of beast, the occasional Great White Shark, like the one that snatched at a teen’s foot a couple years back.)

Every rustle as the kids progressed could be a threat, supernatural or otherwise — a hungry coyote pack, a drunk tourist, a screeching bird, a disembodied spirit. The scrum of competing forces continued to intensify as the weekend ticked away. With Sunday upon them, kids, especially, could be forgiven for giving up, accepting Vail’s sad fate. But for however many who drifted back home, a tenacious few refused to give up.

Hearts sank, one by one. Despite tireless searching by those motivated by concern for Vail, by the adventure of it all, by the money, all came up equally empty-handed. Just as there was little that locals could do to eradicate the island’s coyote population, no amount of wealth could sway nature. Over the weekend, anything had seemed possible. Now, there was little question that Vail was gone forever.

On Monday, a teacher outside Sullivan’s Island Elementary —located approximately 600 feet from where Vail originally went missing —was lining her students up to begin the day. Kids who had been out all weekend searching would have shown bleary eyes, barely able to stand still in the line-up. The teacher prepared for another day. A day that, for so many in her position in America, could bring long hours, limited resources and intrusive parents wanting to look over her shoulder. The wealthiest parents always wanted to ensure their children were challenged and being pushed to reach for their dreams —or, at least, for the parents’ abandoned dreams. The teacher, meanwhile, had her own challenges, her own dreams —like Brooke Gordon herself, who had once planned on teaching.

Unseen, behind her, something was stalking through the grass. She nearly jumped at the feeling of fur brushing against her leg. Astonished, she looked down to see the Doll Face Persian.

The children were next to notice. Nothing could have been more shocking. Here she was, the animal that had captured all their thoughts and imaginations, that had inspired an island-wide search! Not just that the cat was standing right there, but that she had somehow found a way to survive for nearly 72 hours. It was as though the cat had recognized the effort put out across the island by the school’s children, and wanted to reward them. What was that little kitty’s weekend like, and was it anything like theirs? Did she hide? Did she have adventures and horrors? It is not hard to imagine the wide eyes and dropped jaws as the kids, having traded in the search for the schoolday, saw their quarry purring, waiting to be picked up.

Vail was returned home to Brooke Gordon and her family. Although dehydrated, Vail was given time to recover a clean bill of health. Although initial reports stated that a teacher had claimed the award, local rumors swirled that the educator was forced to hand over her prize with the school district since the pet was discovered on school grounds. A district spokesman clarified that no reward money was claimed by the school. According to some, Brooke quietly donated another ten thousand to the school.

Vail’s three-and-a-half day adventure brings into focus how we coexist. How we coexist with wealth. How we coexist with nature. And how we coexist with each other.

No matter what resources humans may have at hand, we can only exert so much control over the world around us.

“I don’t really want to see nature disappear completely. It’s about achieving a healthy coexistence,” says Marie Sollitt of the Edgar Allan Poe Library. “The challenge is finding out what that is.”

For the cat’s part, Vail’s pampered life resumed, and she can look back with the wisdom of a three year old cat. As she curls up in a seaside window with a view of the old lighthouse, she could reflect, to the extent cats do, on how an underestimated feline survived. Given such incredible odds, Vail fared better than anyone could have expected. Even following the cat’s safe return, some still questioned the circumstances of Vail’s safe arrival back home.

With the news of the rescue spreading, Mike Doyle of Sumter, South Carolina, posted a tongue-in-cheek viewpoint on Facebook. “Don’t be naive people,” he remarked. “The cat orchestrated the whole thing. Planned his disappearance, found a willing accomplice in the teacher and executed the whole thing flawlessly.”

***

Dustin Waters is a writer from Macon, Georgia, currently living in D.C. After years as a beat reporter in the Lowcountry, he now focuses his attention on historical oddities and the merits of professional wrestling. His work can regularly be found in the Washington Post’s Retropolis section.