A respected professor shot dead through the window of a stately mansion. A quaint New England town shaken to its core. Enemies hiding in plain sight become suspects.

—

There were two people in the rambling Victorian that night.

It was May 1940 in a town a hundred miles west of Boston. The professor’s wife, who headed up a half-dozen social committees around town despite her poor health, excused herself by 9:30 pm and headed upstairs to bed.

In his smoking jacket and brown leather slippers, diminutive, white-haired, 66-year-old Lewis Allyn had settled into an armchair with a novel. The novel, remarkably considering how things turned out, was called The Gun. Sometime after 10 p.m., he put the book down and padded to the glass-paneled front door.

Gunfire from an automatic weapon exploded, striking Lewis in the face, shoulder, and chest, sending his glasses flying, leaving a bullet lodged in a wall and Lewis dying on the floor.

Alice Allyn stumbled upon the shocking sight. Patrolman Malcolm Donald and another policeman arrived to find Lewis lying amid scattered throw rugs and disordered furniture.

Mild-mannered chemists don’t get gunned down execution-style in their parlors, especially in small towns like Westfield, Massachusetts. Yet after the state police swarmed in, snapping crime scene photos and collecting vials of spent shells and samples of dust from the mantlepiece, no one asked Patrolman Donald what he thought had happened. The Hampden County DA didn’t even contact him for six months.

The beat cop was right to sense flaws in the investigation of a case that still stands as the only unsolved murder in the history of Westfield, now finally on the cusp of a solution. It wasn’t until decades later that the bizarre events of that spring night in 1940 would begin to make sense, revealing the two-sided coin of small town life, somehow both transparent and impervious to examination.

Small town murder, it turned out, was all about following the footsteps of a killer who knew how to leave none.

Back in 1940, Chief of Police Allen H. Smith, 47, seemed like just the right person to crack the case. He had been on the force for 21 years, so he knew the town and its residents inside out. He was diplomatic, having stepped in a few years earlier to successfully avert a strike by tobacco laborers. He had been appointed chief only a year before the murder, making it the perfect opportunity to show what he could do.

All Westfield was abuzz with news of the murder, which hit the front page of The New York Times. When it came to the victim, there was plenty to chatter about.

Professor Allyn had made a national name for himself as a whistle-blower. For a long stretch, Allyn had pocketed $5,000 a year — the equivalent of almost $130,000 today — as a regular contributor, then editor, for Collier’s, a best-selling magazine known for its investigative journalism. Thanks to Allyn, Collier’s editor Norman Hapgood exulted, “Babies are cooing in their mother’s arms and children are toddling upon the streets who would be in their graves.” Additives and preservatives were completely revolutionizing commercial food. While they prolonged shelf life and gave food dazzling colors, their impact on human health was poorly understood. The chemist had raised alarms about sulfurous acid, coal-tar dye, arsenic, dirt, and wallpaper glue in candy, grass seeds in strawberry jam, formaldehyde, borax, and salicylic acid in canned goods. Allyn’s criteria for pure food became known as the Westfield Standard.

From outward appearances, Allyn was an upstanding citizen: family man, deacon for a local church, town board volunteer. The local boy who’d made good. His boyish good looks, exuberant white hair, and apparent sincerity also earned him a reputation as a ladies’ man. Legions of female students vied for his attention at the Normal School, the teachers college where he taught something called kitchen chemistry.

That also left corresponding legions of men — fathers, boyfriends, husbands — who could carry grudges.

In the early 19th century, Westfield had fed a global appetite for whips: delicate whips for dressage and carriage horses, heftier braided ones for livestock. When cars became available, most of Westfield’s 40-plus whip factories shut down. All these years later, Westfield was still known as Whip City. Now it was known for the shocking murder of arguably its best-known resident.

Chief Smith dangled a $500 reward for information leading to an arrest, but the department had a problem when it came to this case.

The problem came in the form of town gossip that the married Chief Smith had been having an affair with a curvy redhead who was also involved with Allyn, producing a fatal love triangle that the police could never allow to be exposed.

Nearly 60 years later, in the late 1990s, newly appointed Westfield detective Michael McCabe sat down with his own police chief and brought up the unsolved murder of Professor Allyn, likely the last thing on anyone’s mind at that point. The town had a fresh set of troubles by then, but the case stuck in McCabe’s craw, the fact that a murder had been carried out right here in Westfield and justice still hadn’t been served.

McCabe had known about as much about the Lewis Allyn murder as everybody in Westfield did, until with his promotion he inherited a pile of cold cases many other busy officers would have pushed to the side. One of those cases was Allyn’s.

Modern forensics, the detective was convinced, could solve the case if he could find new evidence. That was a big “if.” As far as McCabe knew, no physical evidence had survived, and no one in law enforcement had touched the case in decades. Their departmental integrity was also at stake. He wanted, he told the chief, to see if there was any truth to the long-standing rumor that the Westfield police department had been involved in the crime or a coverup.

McCabe’s name is stitched in gold on the breast pocket of a navy-blue uniform hanging in his office, but more often he would be found in a polo shirt — he has one advertising the local funeral home — khakis, argyle socks, and loafers.

With salt-and-pepper hair, metal-framed glasses and those socks, McCabe comes off more as a jovial uncle than a hardboiled detective. “I figure the only way to solve it is to keep it alive,” he says about the Allyn case. People obsess about cold cases for reasons that are rarely as straightforward as they make them out to be.

McCabe had moved from Newburgh, New York, to Massachusetts when he was 12. World Series memorabilia on his walls point to his being a lifelong Yankees fan. He also has plaques commemorating two completed Boston Marathons. On his desk, amid papers and files, are framed photos of his wife and daughter.

As a kid, his home life was messy. His parents were divorced; one struggled with mental illness. The Westfield juvenile crime detectives became surrogate father figures. It was the era of Colombo, The Rockford Files, Starsky & Hutch. He decided to major in criminology at Westfield State, soon joining the police department that would become his professional home for the next thirty years. Just as his childhood heroes had believed, he came to feel that every case, no matter how ice cold, deserved to be solved.

Let it go, the chief told him. But McCabe couldn’t let it go. It was as though the open case taunted him from its decades of slumber. If he could solve it, it would show any case could be solved.

Then the “let it go” chief retired. McCabe approached the new chief, a friend as well as a colleague. This time he was on a more even playing field with his boss. “John,” he said, “do you think we could find anything at all?” John Camerota responded, “Mike, look anywhere you want.”

A major roadblock awaited McCabe’s hopes of restarting an investigation: no police files. The Allyn case files had been mysteriously missing for as long as anyone could remember. The assumption was that Chief Smith had destroyed the file in order to protect himself because of the whispers about his and Allyn’s shared mistress. There had also been a persistent rumor within the department that a .22-caliber automatic pistol — the type of gun used to kill Allyn — had been missing from the inventory since the murder. A missing gun might seal the deal that Smith indeed had been involved.

McCabe knew murder case files were kept in a locked cabinet in the office of the administrative secretary to the chief. There was no chance of anything coming so easily. McCabe did find an old letter from the 1940s, written under the alias “Ellery Queen,” addressed to the department about the case and urging new avenues of investigation. Then, once McCabe started poking around more, he found something tucked away in the recesses of the chief’s desk. They were photo negatives. Black and white, they had no date or case number, just the label “Allyn.”

Already in over his head trying to solve the Allyn murder, Chief Smith faced dissension in his own ranks. Patrolman Malcolm Donald, who had continued to feel that his concerns around the case had been ignored, dashed off a letter to the department. In it, Donald pushed the idea that male faculty at the Normal School felt animosity and jealousy toward Allyn because they thought he was “favorited” by the female students. Of course, that potential for trouble stemming from Allyn’s flirtations and relationships with women also lined up with the suspicions about Donald’s boss, Chief Smith. To avoid repercussions, Donald signed the letter “Ellery Queen,” a fictional mystery writer and amateur sleuth.

For those who had observed Allyn at work, it was not difficult to see how his dynamic with the many young women in his circle could have spiraled out of control. He was teacher, mentor, father figure, and boss all at once. At a domestic science exposition in New York’s Madison Square Garden, Allyn could be seen in his suit, vest, and bow tie, gazing into the distance as young women at his side wearing oilcloth aprons worked with pipettes and scales at a booth mocked up to look like a lab. Women in floor-length skirts and feathered hats crowded around to watch the female Normal School students “Allynize” samples of tea, coffee, cocoa, and soap, serving as Allyn’s de facto, presumably unpaid, lab assistants.

Sometimes, with a showman’s flare, Allyn would open a can of peas, add hydrochloric acid, and dip in a butcher knife. Copper sulfate added by the manufacturer to make the peas a brilliant green would leach onto the knife.

Intriguing puzzle pieces materialized around Westfield, all of which took place near the time of the murder: an unidentified man sitting in a parked car on a side street an hour before the murder; a teenaged neighbor of Allyn’s said to have bought .22-caliber bullets at a local hardware store “for a friend;” a man who’d been seen alone at the railroad station shortly after the crime who boarded a train for Pittsfield and paid cash for his ticket, then sat with his face partially shielded.

For those who believed that Chief Smith was implicated, the top police official had to fabricate scenarios to exonerate himself; for those who believed Chief Smith simply had been with the wrong woman at the wrong time, he had to put these jagged pieces together before his name was permanently tainted.

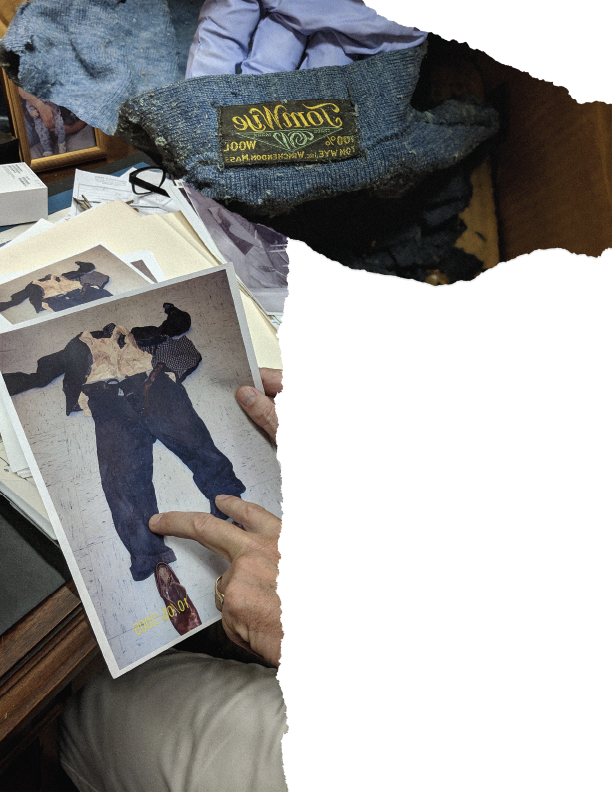

With the newly discovered negatives printed, Detective Mike McCabe was likely the first officer to hold Allyn crime scene photos in almost 60 years.

The photos revealed Professor Allyn sprawled on his parlor floor. He lies face up, eyes open, mouth agape next to a straight-backed cane chair and a profusion of throw rugs on a parquet floor. The checkered lining of his smoking jacket is visible where it was flung open. His right pant leg has ridden up; his right hand is pale, fingers limp. One of the thin black socks on his slipperless feet has holes at the heel. His smashed glasses have come to rest near a baseboard a few feet from his head.

That was not to be the last piece of evidence that seemed to fall out of the sky, almost as though the space-time continuum was opening up in response to McCabe’s stubbornness. Sometime after the discovery of the negatives, a state trooper strolled into the station and plopped down a discolored cardboard box on McCabe’s desk that, had the trooper not decided to lug it over, likely would have been tossed out with the latest pizza boxes. It looked like something from a garage sale and smelled musty, like a long-shuttered attic.

What McCabe found inside was a minor miracle. There was a blood-stained collared shirt, yellowed with age, a smoking jacket, wool slacks with a leather belt still threaded through the belt loops, suspenders, and leather slippers with decorative stitching along the edges. There were also spent shells and glass vials with cork stoppers, labeled by hand in blue curlicue script, containing something that looked like dust.

When he first examined the contents, McCabe instantly recognized what Lewis Allyn had been wearing the night he was killed. It was all there in the crime scene photos: the shirt, the smoking jacket, the wool trousers. A lone slipper near the body and another some feet away.

In 2015, by now a senior captain, McCabe was shocked to find additional photos of the Allyn crime scene in a place even more unexpected than the crevices of a desk or a disintegrating box: social media.

Posted to a Facebook page were what appeared to be high-resolution images of Allyn in the aftermath of the murder, as well as locations within the house that could enhance their understanding of any possible scenario that happened the night of the murder. McCabe had never seen these photos before, and he had never heard of the man who posted them.

McCabe knew that in 1955, the police department, then in the basement of City Hall, lost dozens of files in a massive flood. Among them were files from the Allyn investigation.

Consulting an old city directory, McCabe learned that the father of the Facebook poster had at one time been a maintenance worker in City Hall. When McCabe got the son on the phone, he told McCabe his father had rescued the water-damaged files from the trash and stored them in his garage for decades. The son, thinking the gory images were cool, kept the photos when his father moved to a nursing home. Now, on the 75th anniversary of the murder, he’d posted them on Facebook.

That file is important, McCabe told him. It should be returned to the police. Could he have it, or at least see it? No, the man’s son told him. I threw it away.

It was a tremendously frustrating revelation, and scarcely believable. Had the man really thrown these away after salvaging them, and if not, why tell that tale? “To this day,” McCabe would note, “I don’t really know what he has.”

Whenever he wanted to check up on his growing reconstruction of the Allyn case, McCabe would walk down gray metal stairs and into a basement gym, where a patrolman in a muscle tank top lifted weights while another’s feet pounded on a treadmill. A wall-mounted TV would usually be tuned into ESPN.

Though to the naked eye, what McCabe had collected was a bit of a macabre mess, the case’s internal compass, the investigator believed, appeared finally to be pointing right at the killer.

As the momentum of his long search ramped up, McCabe got a phone call. The man on the phone told McCabe he’d been working in his garden in Westfield and came across a very old holstered gun buried under some rose bushes. McCabe got goosebumps. Do you, the man asked, want to come see it?

Lewis Allyn made a series of choices, personal and professional, that flooded Westfield with a grab bag of motives to do him in.

As a member of the local Board of Health, Lewis Allyn would distribute lists of food he declared wholesome. But then he started listing offending products, naming the merchants who carried them. To certain grocers, this was a threat to their livelihoods.

Allyn reportedly invited affronted grocers to his third floor, 20-by-25-foot laboratory (today the Westfield Gas and Electric Company). “He taught them as he was teaching the girls,” nationally known author Peter Clarke MacFarlane wrote in Collier’s in 1913. “They became his friends and cooperators.” But they were not his friends. A local reporter wrote, “If curses loud and deep could kill, [Allyn] would have been annihilated.”

Allyn and the Board of Health asked grocers to pledge to his so-called Westfield Standard. By signing on, the grocers agreed not to sell deceptively labeled foods or any foods containing artificial or chemical acids, salts, or coal tar dyes, a seemingly civic-minded agreement that ultimately served to reinforce Allyn’s authority and power. Twelve grocers signed. One refused.

Not surprisingly, Allyn deemed products from Nabisco, Kellogg’s, Domino, Crisco and Heinz — some of the most prominent advertisers for his longtime employer Collier’s — entirely safe. This wasn’t lost on Allyn’s circle of critics. The tide began to turn against him. The state Board of Education discovered Allyn had never received a degree, calling into question his teaching credentials and professor title. A state senator demanded a stop to what he termed Allyn’s “shameless propaganda.” The senator thought the Westfield Board of Health was complicit in legitimizing Allyn’s “absurd claims” about food safety that helped put Westfield on the map for something more lofty than its whip factories.

Separately, the American Chemical Society’s St. Louis chapter moved to expel Allyn for “arousing unnecessary alarm among the uninformed public,” influencing the purchase of food and beverages and libeling US food and drug officials.

Allyn replied that the attack from St. Louis was led by a chemist who represented the interests of Coca-Cola and saccharin. “That fraud, deceit, and danger lurk for the little child in soft drinks, the writer knows too well,” Allyn wrote, in this case quite presciently. Despite being “dogged by detectives, slandered, prosecuted, threatened with legal suits,” he vowed to keep speaking out about adulterated food.

While the forces of evil — as Allyn saw it — sought to take him down, he made his movie debut. The black and white film Poison revolved around a tycoon who’d made his fortune on adulterated foods. His horrified son seeks out Allyn, who plays himself. The role was a statement in itself — no matter what adversity he encountered, Allyn would get the last laugh, in this case even using a scandal about his credibility to claim a greater share of the public spotlight.

Cutting ties to the pure food movement, the Board of Health, and teaching, Allyn opened his own lab, where he was paid to test beverage samples for alcohol content during Prohibition. He took the stand in Hampden County Superior Court to testify that bottles seized from bootleggers contained bathtub liquor. For this reason, L. Michael McCartney, one of the founding members of the criminal justice program at Westfield State, finds it plausible that Allyn could have been the target of a Mob hit. He was shot in the mouth — a typical Mob message for stool pigeons.

Allyn also embarked on his own lines of research. He was awarded patents for a method to retain beneficial iodine and sodium chloride from evaporated sea water, as well as for a means to create a vitamin-rich, shelf-stable food product. He was working on a sugar substitute to replace saccharin. From all appearances, life was chugging along.

But Allyn believed Nazi government agents were after his food concentrate formula. And a soft drink manufacturer wanted to get its hands on his sugar substitute.

Walking through town, Allyn could by now spot enemies, real and imagined, anywhere he turned. A baker had once sued him for libel and slander when Allyn wrote a piece for local papers about a bakery that cut its vanilla with poisonous wood alcohol.

A few months before the murder, Allyn’s wife had told police that the so-called Thirteenth Grocer — the one who’d refused to sign the pledge to only carry Allyn-approved food products — had shown up at their house. Alice was active in the congregational church, the Westfield Women’s Club, the Tuesday Morning Music Club, and the Women’s Auxiliary of the YMCA. She was hosting one of these groups when a man with what she described as a European accent let himself in the unlocked front door. After arguing with her husband, he’d left in a huff.

Some of Allyn’s many affairs inevitably came to be known. Besides the mistress who was reportedly sleeping with both Allyn and the chief of police, whispers flew about a liaison with a neighbor’s wife.

Then there was Alice herself. “If his wife had the means, she sure had the motive,” criminologist McCartney has noted. “And the opportunity.” A .22-caliber is “the kind of gun a woman could handle. A very small gun. It didn’t even kill him immediately. That’s probably why the assailant had to shoot him four times.”

According to Allyn’s grandniece, Helen, the family always thought the killer was someone he knew. “He had to know who it was,” she said. “And just before he was killed, they said he was acting kind of nervous. Like he wasn’t himself. Like he had something on his mind.”

McCabe rushed to the spot where the local caller had dug up a gun in his garden, a kind of time capsule. McCabe was floored to see that the gun was a high-standard .22-caliber pistol, exactly the make and model ballistics tests identified as the weapon that killed Allyn. Its vintage appeared to be of the era of Allyn’s murder. And looking up from the spot where it was buried, the investigator who would not give up was gazing upon a property that had belonged to the very figure who had become McCabe’s most viable suspect.

On May 7, 1940, Allyn returned from Westfield Testing & Research Laboratory, his private lab in a brick building downtown on Elm Street, a mile and half away. He was wearing a lab coat over dark gray trousers, a leather belt, a white cotton undershirt and button-down shirt. When he got home, he swapped the lab coat for a smoking jacket, then put on brown leather slippers with a trimmed edge.

The fanciful, ornate, six-bedroom house had a turret — a round room circled with windows — a shingled, curved facade, a wraparound porch, and an expansive lawn. It sat in a well-heeled residential neighborhood, walking distance to Westfield’s quaint downtown.

Settled in the parlor in a Morris chair with slatted wood sides and doilies on its cushions, Alice in bed upstairs, Allyn picked up The Gun, a novel of betrayal and war set in the early 19th century.

As he read, a figure negotiated the way along the front path, a .22 automatic loaded and ready. Barely bigger than the assailant’s hand, it slipped easily into a pocket or purse. McCabe would come to believe this weapon alone argued against the approaching intruder being a mobster or a government assassin.

The suspects began to narrow.

In his parlor, Allyn was in a virtual fishbowl, visible through multiple windows, an easy target for a high-powered rifle. This was personal. The killer had a debt to settle in person, and needed Allyn to know why he was paying it.

A little after 10 p.m., something made Allyn put his book face down on the floor and head toward the glass-paneled front door. Allyn’s walk to the front door minimized the chances that the assailant could have been Alice, who would have been approaching from inside the house.

Another suspect moved to the unlikely side of the ledger.

Alice, reading or half-asleep, later recalled hearing someone running up the five steps to the veranda. A couple of years after the crime, True Detective magazine quoted Alice saying that because the person ran to the door, she assumed he or she was not a stranger. The porch light was on and the front door unlocked so that Anna, the girl living with them in exchange for household chores, would not disturb them when she returned from a night out at the movies.

Alice heard the door. “The door opened quietly but I heard it distinctly,” she said. “I heard Mr. Allyn’s voice but it was indistinct, inarticulate.” Then she heard two people scuffling; it sounded, she said later, like “horseplay.” Then five shots were fired.

A visitor would not have drawn much attention by walking up to the house or parking nearby and slipping along the darkened path. A local merchant would not be expected to call at that hour — but perhaps this person had shown up unannounced in the past, and knew that the lights being on in the parlor meant Allyn had not turned in for the night. Maybe he had watched from afar and knew Allyn typically read in the armchair before joining Alice upstairs in bed.

The assailant left no sign of a break in, perhaps walking through the unlocked door to make his or her move before Allyn recognized a threat, or pushing through the door just as Allyn opened it. They were now face to face, standing on Oriental throw rugs, the dining room visible behind them with its china cabinet, rocker, wicker and cane-seated chairs, framed pictures on the walls, a fireplace with andirons. The exchange may well have begun calmly, but escalated. An industry spy who wants a formula, McCabe would deduce, would confront Allyn, not kill him. You don’t silence the person who can give you the information you’re looking for.

Another suspect down.

A struggle ensued, evidenced by the state of the rug and furniture. If Allyn had started to fight off the attacker, he switched tactics when he spotted the gun. A rifleman and hunter, Allyn knew the damage bullets, even relatively small ones, can inflict. He backed away, raising his hands protectively. A bullet struck him, passing through his left hand and coming to rest in his right shoulder. After the first shot, the professor turned to flee, but in the autopsy photos, small black craters in his abdomen, below his right nipple and in the center of his chest, would indicate the bullets came from the front, aimed at the heart. One to the face sent his eyeglasses flying.

A veteran police officer such as Chief Smith could have devised a dozen plans to murder a man that were less messy and risky, and certainly would have destroyed the photographic negatives when he had the chance, of which he would have had many.

Chief Allen H. Smith — another suspect to cross off.

There were so many pops, as Alice called them later, but they were not very loud. The police would surmise the gun had a silencer. The attack was calculated, but this moment of rage had built for a long time.

McCabe, weighing the newly discovered vintage .22 in his hands, could have done a double take as he stared at the home where the weapon had been buried for so long. It used to belong to the so-called Thirteenth Grocer, who had refused to sign one of Allyn’s self-serving pledges, the same man who went to the Allyn house before the murder and was heard arguing with him.

Allyn staggered from the living room through the dining room and into the kitchen, trailing blood. He collapsed, leaving a bloody handprint on the floor, then got to his feet and moved back toward the front of the house, where he grasped the mantle, creating another handprint.

Here was the last of the old chemist, having lived a seemingly charmed life in a grand house as he stomped on expendable people such as the Thirteenth Grocer. Revenge echoed with each report of the gun.

The attacker pulled the trigger again and again but, inexperienced in murder, he couldn’t seem to deliver a mortal blow. The gunman fled, not knowing what, if anything, Allyn might say with his dying breath, a crucial loose end left untied.

The assailant slipped anonymously into the night.

Alice found her husband kneeling next to the cane chair. She gripped his shoulders but he slumped to the floor. By the time Patrolman Donald and a doctor arrived, he was already dead.

aptain Mike McCabe traced the unearthed pistol to its manufacturer. Like the murder weapon, it was a Hi-Standard .22-caliber automatic pistol with a magazine capacity of ten bullets. This type of firearm had been manufactured since around 1932, used primarily for target practice.

But this particular gun, McCabe learned by its serial number, had been manufactured the year after the murder.

One year after!

At first, it seemed like maybe this exonerated the Thirteenth Grocer. But did it really? What were the chances a weapon identical to the murder weapon would be hidden at the home of that grocer? Just as chemists didn’t get gunned down in sleepy Westfield, upstanding citizens didn’t usually bury guns in rose bushes. If the Thirteenth Grocer killed Allyn and disposed of the murder weapon, he likely would have done so far from his own house so it could not be used to incriminate him.

The grocer would have been relieved when the media and law enforcement spun tales of tawdry affairs and foreign intrigue, but certainly he had to be wary of Malcolm Donald, who agitated for more avenues of investigation and became chief of police when Allen Smith died. The murderer grew increasingly uneasy. It stands to reason that the murderer’s weapon of choice was a .22, and that now he would get another one soon after — this time as a kind of insurance policy for his own protection. There was no shame in owning a gun — they were as widely advertised as cigarettes — yet this man buried it, snugly encased in its holster. Nobody — even his family, so it seemed — could be permitted to know he had it. But in its shallow hiding place it would always be near at hand in case someone came for him out of revenge, extortion, or some other blowback from the murder. It would be there in case he ever felt as paranoid — with good reason, as it turned out — as Allyn had in his final days, in case he ever sensed that someone was looking for him in a moment of reckoning. That someone did come — though much later — in the form of Mike McCabe.

The name of the now-deceased grocer is not difficult to find, but McCabe prefers not to share it publicly yet.

The situation of a small town murder is singular. In a small town everyone knows one another, but that also means everyone has plenty of reasons, small or large, to dislike anyone else. In a small town you know everybody’s name, but a criminal knows yours, too; knows how to hide in plain sight; knows how to win your trust; knows your secrets that you might not want to come out if you pry too much into other’s closets.

Reportedly Chief Smith eventually admitted to a confidante that he had an affair with Allyn’s mistress, though insisted it began after the murder and that they became involved only when the woman was questioned, which would have been a terrible lapse of judgment even if not part of a coverup. We will never know exactly what Chief Smith did or did not find before he died relatively young in 1950. Malcolm Donald, who had itched to solve the case from the beginning, made no discernible progress once he succeeded Smith as chief.

Although Alice Allyn had always been said to suffer from ill health, she would go on to live long after her husband, passing away at 104 years old. Daughter of a prominent attorney and graduate of a Normal School, Alice was no fool. Maybe her malady at the time was depression stemming from the humiliation of her husband’s infidelities, and in her husband’s sudden and violent death there was a measure of rebirth for her.

From that miraculously rediscovered evidence box, McCabe gingerly holds up the yellowed, bloodstained shirt that was once white. In 2018, the Golden State Killer — a California man accused of a series of decades-old rapes and murders — was identified through genetic genealogy. The perpetrator’s DNA may well have been added to Allyn’s in their struggle, both ending up on this shirt. But finally putting the case to bed once and for all by extracting DNA is an expensive proposition, and no one has offered to pay for it.

It’s hard to know who to root for between Allyn and his enemies, but it’s easy to root for McCabe’s tenacity to find the answers, to bear out our innate confidence in restoring order to disorder and in finding justice for every murder, however belated, and in our capacity for persistence.

“I’m pretty much convinced this shirt probably contains all the elements of the crime that we would need,” McCabe says, “because he was clearly fighting.”

***

DEBORAH HALBER is a Boston-area science writer, journalist and author.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us