When a spring breaker goes missing, a seasoned investigator uncovers devil worship and a sinister cult at the heart of the drug trade.

The scent of gunpowder hung heavily in the air in the bustling Cuauhtemoc neighborhood in Mexico City, just blocks from the Aztec ruins of the Templo Mayor. At the corner of Rio Sena and the Paseo de la Reforma, hunkered-down groups of federales trained their assault rifles at the blasted out fourth-story window across the street. Thousands of rounds had been exchanged in the nearly hour-long gun battle before the shooting from above had abruptly stopped.

The federales, crouching behind bullet-ridden cars, squinted through their sights, expecting at any moment to see in that window a man who had become known to authorities as the incarnation of pure evil, a cult leader who commanded the powers of the devil himself. A tense moment passed before the street-level door to the decrepit apartment building burst open and a young woman ran out, face full of fear.

“Thank God, I’m saved!” she screamed, practically falling into one of the federale’s arms. “I’ve been through hell since they kidnapped me.”

The men continued aiming their weapons at the darkness beyond the shattered window above, wondering if evil would show its face.

APRIL FOOLS DAY 1989

FIVE WEEKS EARLIER …

A small group of Mexican federales had just finished setting up a roadblock in the dusty, sweltering flatlands east of Matamoros. The scene was familiar, part of the Mexican agents’ unceasing — if futile — efforts to stem the tide of narcotraficantes smuggling their goods across the brown-green waters of the Rio Grande. The work could be numbing in its repetition. But now, several hours into their shift, as the agents wilted under the glare of the punishing afternoon sun, their stupor was interrupted by a red Chevy pickup that blasted full-speed through their warning signs and orange cones. The truck’s young driver acted as if the startled federales weren’t even there.

“He did what?” Comandante Juan Benitez Ayala asked in astonishment later that afternoon, when one of his agents called to report the incident. The federales had recognized the truck: it belonged to “Little” Serafin Hernandez, an arrogant, dim-witted young member of the powerful Hernandez drug smuggling clan, a family dynasty whose control of the region seemed to be expanding daily. The agent on the phone told Comandante Benitez that he and his fellow officers had trailed Little Serafin to a hillside ranch sixteen miles west of Matamoros. Poking around the site later, the agents had stumbled across a demonic-looking statue with a face made out of seashells.

The superstitious Benitez knew instantly what the statue meant: Black magic. It wasn’t a sign he took lightly. Dark forces must have set up shop in the hills around Matamoros.

The 35-year-old Benitez had been in Matamoros for a month, tasked with battling the endemic drug trafficking and police corruption that infested the city. The comandante’s youthful features, slim figure, and sharp black eyes weren’t the only things that set him apart from the majority of his colleagues: his relative lack of corruption provided an equally marked contrast from his fellow officers.

Adding to the problems that threatened to overwhelm Benitez in his new post was the missing American college student, Mark Kilroy, who had disappeared during a spring break vacation shortly after Benitez had arrived in the city. American and Mexican officials were pressuring the comandante daily for a break in the case. The press was equally relentless. While young Mexican men went missing in Matamoros all the time, those men had brown skin, and few resources were devoted to determining their fate. Mark Kilroy, however, was American, and white, and the Texas police, the FBI, and U.S. Customs — not to mention Kilroy’s frantic family — weren’t about to let his case slip into obscurity.

Benitez decided to learn all he could about the Hernandez drug smuggling family. Why had Little Serafin seemed so unconcerned about blowing through the federales’ roadblock? What was the family getting up to at their Santa Elena ranch outside of Matamoros, where Benitez’s men had tracked Little Serafin’s truck? DEA agents in Brownsville, Texas, provided Benitez with the cellular phone information for eleven different numbers registered to a company called Hernandez Ranches. Benitez was taken aback by the gang’s arrogance — they hadn’t even bothered to employ a false name.

The first thing Benitez overheard when he started eavesdropping on the Hernandezes’ phone calls was Little Serafin bragging about a massive load of drugs the family had smuggled over the border the night before. Then Little Serafin carelessly dropped the home address of his uncle Elio, one of the family’s leaders. He also mentioned a man he called El Padrino. “Who do you think that is?” Benitez asked his agents. But none of the men had heard the name before.

Later that day Benitez and his agents picked up Little Serafin and another gang member at Uncle Elio’s house, where they discovered a cache of weapons and residue from the previous night’s drug shipment. Benitez handcuffed the two smugglers and drove them to Rancho Santa Helena, where the agents found sixty-four pounds of marijuana and another pile of weapons. Yet even as the two men were arrested, they continued to smirk, appearing wholly unconcerned. When Elio Hernandez and several other family members were arrested later that afternoon, they evinced the same lack of concern, laughing among themselves even after enduring hours of interrogation.

The only person who trembled when arrested was the ranch’s grizzled caretaker, Domingo Bustamente, who seemed as frightened of the police as he clearly was of the Hernandez family. But with the Hernandezes now behind bars at the police station, Bustamente’s fear of the police took precedence, and he required little prodding to talk. Yes, he told Benitez, the Hernandezes smuggled drugs, huge amounts of them. Smugglers came and went at the ranch all the time. And not just smugglers: “There are others. They are treated very badly.” A few weeks before, Bustamente said, there had even been an American.

Benitez felt a sharp tug at his insides. He thought immediately of a young man named Mark Kilroy and realized that what he had assumed was a routine drug trafficking case may have just taken a sinister, and politically treacherous, turn. He needed the Hernandezes to confess everything they knew, and now. Using a form of interrogation that the federales euphemistically referred to as “moral pressure” — physically beating the suspects and shooting soda water laced heavily with Tabasco sauce up their nostrils — Benitez and his men quickly forced the sneering family members to talk.

Little Serafin was the first to babble. “He told us our souls were dead,” the drug trafficker said, no more bothered uttering macabre statements like that than if he were describing the weather. “When that happens, you can do anything. To anyone.”

Who? Benitez asked. Who told him that? Little Serafin answered calmly: El Padrino. The Godfather.

Spring break couldn’t come soon enough. Mark Kilroy had finished his last midterm exam at the University of Texas at Austin on a Friday in mid-March and promptly jumped in a car with his old friend Bradley Moore for some well-deserved letting loose. A junior-year biochemistry major, Kilroy took his college work seriously, and was laser focused on attending medical school after graduation. He had given up a basketball scholarship at another school to take advantage of UT’s superior pre-med offerings. Spring break would be a welcome reprieve from his months of diligent studying.

Kilroy and Moore paused in their tiny hometown of Santa Fe, Texas, to pick up two more friends, Bill Huddleston and Brent Martin, who attended college elsewhere in the state. Baseball and basketball buddies, the four had been close for most of their twenty-one years, and they had planned this getaway with the knowledge that it might be their last trip together before graduation launched them into new lives in other locations.

After driving 600 miles through the night, the group arrived at their destination, the spring break mecca of South Padre Island, a sun-splashed strip of pristine beaches and warm Gulf waters off the southern coast of Texas. The tall, blonde Kilroy and his friends were part of the annual pilgrimage to pursue the holy triumvirate of sun, sex, and alcohol. The scene was far from Kilroy’s normal milieu. Shy by nature, and staunchly anti-drug, Kilroy was a responsible young man who participated only sparingly in UT-Austin’s lively party scene.

Once in South Padre, Kilroy, a loving son, called his parents to let them know he had arrived safely. Then he and his friends grabbed a few hours of sleep at the Sheraton hotel before hitting the beach for the wildly popular Miss Tanline contest, a daily spring break event. The four were surrounded by thousands of whooping revelers, some already so inebriated that they passed out in the sand. Kegs were everywhere, and the normally pristine beach was littered with trash dropped by careless students. After pausing for dinner, Kilroy and his friends continued the party later that night with a group of girls they met at the Sheraton.

The following day, the four friends set out for Matamoros, a gritty, thrumming city on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, directly across the border from Brownsville, Texas. With its tourist-trap shops and plethora of cheap bars, Matamoros was a magnet for spring breakers. Kilroy had been to the city the previous year, and he guided his companions down the teeming main drag. The group spent several hours drinking at a gaudy dance club before making their sleepy way back to their hotel.

On Monday, March 13, the third day of their vacation, Kilroy and his friends nursed their morning hangovers on the beach before once again hitting the daily Miss Tanline contest. After dinner they decided to return to Matamoros for another round of late-night fun. They parked on the border in Brownsville, Texas, and walked across the international bridge to the tree-lined Avenida Alvaro Obregon, where thousands of other spring breakers jammed the blocks of bars and dance clubs. Souvenir merchants and drug dealers sold their wares on the sidewalks, while pickpockets slipped between unsuspecting partiers.

Kilroy and his friends started their night at a bar named Los Sombreros, where neon lighting and ear-splitting music assaulted the senses of the college revelers packed shoulder-to-shoulder on the sawdust floor. After slaking their thirst with some warm-up margaritas, the four headed farther down the avenue to the London Pub, which the owners had craftily renamed the Hard Rock Cafe — insignia and all — for the duration of spring break, making it the go-to destination for unaware college students attracted to the familiar sign. By the time Kilroy and the others arrived, the bar was already at full pitch, with drunken males on the balcony throwing empty beer cans at the cattle-packed dance floor below.

His confidence inflated by alcohol, Kilroy approached a woman he recognized from the Miss Tanline contest earlier in the day. Unable to hear each other above the pounding music, the two stepped out in the street to talk, then returned to the bar for margaritas and dancing.

By 2 a.m., most of the patrons had exited the bar and the night’s energy had ebbed. Fogged by drink and worn-out from their third night in a row of carousing, Kilroy and his friends joined the throngs of weary partygoers heading for the Gateway International Bridge back to Brownsville. The four strolled in loose formation, sometimes drifting several yards apart. The hazy streetlights above did little to illuminate the dark, menacing sidestreets just beyond their meager halos.

Kilroy was two blocks from the bridge when a red Chevy pickup pulled beside him.

“Do you want a ride?” a man inside asked.

“Yes,” Kilroy gratefully responded. “I’m so fucked up, I drank too much.” He hopped up into the truck with a relieved smile.

Less than a minute later, Kilroy’s friends caught up with each other. “Where’s Mark?” one asked. Two blocks ahead they could see the lights of the international bridge. Despite their boozy, clouded state, the three friends carefully searched the area, retracing their steps back down the street. Eventually they decided that Kilroy must have crossed the bridge ahead of them. He was probably waiting, ready to laugh at their tardiness, on the other side.

In fact, he was on his way to meet a man so evil that even violent, hardened drug traffickers believed him to be the devil incarnate.

They called the man El Padrino, but his real name was Adolfo de Jesús Constanzo. The dark-haired mayombero (black witch) with the movie star good looks, richly stylish wardrobe, and stern, cold eyes was born in Miami in 1962 to a fifteen-year-old Cuban refugee. Constanzo’s mother was a devoted priestess of Santeria, an Afro-Cuban religion based on Yoruba practices and beliefs that also incorporates elements of Roman Catholicism. When Constanzo was just six months old, his mother brought him to a leathery old palero (priest) of Palo Mayombe, a dark and secretive offshoot of Santeria whose rituals involve animal sacrifice. The palero, who had grown rich partnering with local drug dealers, gazed at Constanzo for several long moments before making his pronouncement: “The child is a chosen one. He is destined for greatness, for power.” The palero offered to become the baby’s teacher in the black arts. Though he was still an infant, Constanzo’s wicked future had already been decided.

Growing up, Constanzo left dead animals on the stoops of neighbors whom he felt had wronged him. The children in his Little Havana neighborhood of Miami learned to grant him a wide berth, wary of the shadowy rituals the boy and his mother performed behind closed doors, and of the foul odors that emanated from their filthy apartment. Constanzo didn’t care: his mother and his palero were his whole world, the spirits of Palo Mayombe his psychic companions. As Constanzo mastered the religion, he also developed a seemingly uncanny ability to predict the future. His mother took great pride in pointing out that he had forecast the assassination attempt on President Reagan.

Constanzo moved to Mexico City in 1983 to work as a tarot card reader, where his predictive powers, and his savant-like knowledge of rituals and spells designed to curry the spirits’ favors, earned him an eager following among tourists and locals alike. His handsome face and high-end clothes also made him a regular presence in the city’s fashion magazines. He quickly gained a reputation as a potent conjurer whose mastery of limpias — ritualistic cleansings of the body for healing and protection — added to his otherworldly persona. Constanzo took special care to cultivate wealthy drug dealers, having long ago taken to heart his palero’s oft-repeated business philosophy: “Let the nonbelievers kill themselves with drugs. We will profit from their foolishness.”

Constanzo also groomed a series of young male lovers whose cultish devotion to the mysterious sorcerer proved all consuming. One of these men, Omar Ochoa, had been infatuated by the occult since he was 15 years old, when an old gypsy woman had read his palm and declared he would one day meet a powerful man who would determine his destiny. “Be ready,” the gypsy had told him. Her words had rung in Ochoa’s head throughout his lonely, painful teenage years, when his sexuality had made him an outcast in a deeply macho culture. Years later, when the small, delicate-featured Ochoa first spotted Constanzo reading tarot cards at a sidewalk café in Mexico City, Constanzo had stunned him by declaring, “You are about to fulfill a prophesy from your youth. An old woman told you to be ready for this moment. Do you not feel I am right?” From that moment on, Ochoa was Constanzo’s eager disciple, giving himself over completely to El Padrino’s desires and whims.

The effeminate Ochoa battled for Constanzo’s affections with Martin Quintana, a hulking, grim-faced man who served as Constanzo’s bodyguard, and who, like Ochoa, had been drawn in by Constanzo’s apparent psychic abilities and by the seductive mysteries of Palo Mayombe. “The power of my religion is greater than anything you’ve ever imagined,” Constanzo told his lovers, promising to teach them how to harness the potency of the dead for their advantage.

Soon Constanzo, Ochoa, and Quintana were sharing quarters in a wildly imbalanced ménage a trois. Ochoa was Costanzo’s “woman,” as Constanzo called him, and Quintana his “man,” and every action of the trio was dedicated to furthering Constanzo’s influence and reputation as a sorcerer. El Padrino initiated his two lovers into the dark practices of his religion: the ritual letting of blood, the renunciation of one’s humanity. “Your soul is dead,” he preached. “You have only me. And you must always obey.”

By 1985 Constanzo’s clients included a shining selection of Mexico’s rich and powerful, everyone from movie stars to high-ranking government officials to murderous crime bosses. One of his most significant clients was Florentino Ventura, the Mexican chief of Interpol, whose insider knowledge Constanzo relied upon when advising drug lords when and where to make their shipments. He was equally popular with the capital city’s underworld, a sordid mélange of thieves, smugglers, and pimps who sought his advice and protection. Constanzo charged as much as $50,000 for spells and limpias that, he solemnly intoned, would shield his criminal clients from the police — or from other criminals. Many of these clients believed that Constanzo’s spells could literally deflect bullets. Others swore that Constanzo granted them the power of invisibility.

Eventually Ventura, the Interpol chief, introduced Constanzo to one of Mexico City’s leading cocaine cartels, the Calzada family, whose superstitious members were quick to accept Constanzo’s supposedly magical guidance. The Calzada family’s deep pockets served Constanzo well, and, by early 1987, he owned a fleet of luxury cars and high-end properties in Mexico City. But this money, although significant, didn’t satisfy him. His palero had taught him that he was destined for power, for ultimate wealth. That was the whole point of Palo Mayombe: to harness the forces of darkness to make yourself triumphant, even invincible. Constanzo may have strutted the streets of Mexico City like an idol, trailing followers in his wake, showering his lovers with fine jewelry and clothes and sports cars, but he felt stymied in his role as a sidekick to the men in the region who wielded real power. So even as he insinuated himself into the lives of the smugglers whose products serviced the insatiable American demand for drugs, he was imagining a larger future: Constanzo wanted to take a piece of the lucrative drug trade for himself.

In April 1987, convinced that his magic alone was responsible for the Calzadas’ continued success, he demanded from the family a 50% partnership in their business. But Guillermo Calzada, the clan’s hardened leader, refused. Spiritual guidance was one thing; the sharing of profits a different matter altogether. Constanzo was enraged, telling himself that he’d been foolish to make the Calzadas wealthy. They weren’t customers, he decided, but rivals. And rivals, his palero had taught him, were meant to be sacrificed. The words of his old teacher back in Miami rang in his ears: “In blood there is power — particularly in human blood.”

“It’s time for a new ritual,” Constanzo told Quintana, his bodyguard and lover. “Will you follow me?”

“Yes, Padrino,” Quintana answered. “I will follow you.”

On the last day of April, Guillermo Calzada and his entire family mysteriously vanished. When the police searched Calzada’s office, they discovered burned candles and other remains of what appeared to be a religious ceremony, along with large quantities of blood. Five days later, two dismembered, cord-bound corpses washed up on the grimy banks of the Zumpango River. By mid-May, authorities had recovered from Mexico City waterways the remains of another five bodies. The corpses were so mutilated that only three could be identified: Calzada’s bodyguard, his secretary, and his maid.

El Padrino, it seemed, had exacted his revenge.

With the Calzada family murdered, Constanzo set his sights on finding new benefactors. It was this search for a new family of drug smugglers that gradually drew his attention to Matamoros. Matamoros, a city of wild inequality, a place where only a short bridge separated the United States and Mexico, was playing an increasingly major role in the transport of illegal drugs.

Among the city’s major players was the Hernandez family, which was currently in disarray following the murder of their longtime boss, Saul Hernandez. Rife with internal discord, the family was flailing, their drug business in dramatic decline. They were in desperate need of a leader with sharp intelligence and vision. Someone like him, Constanzo believed. The only question now was how to infiltrate the formerly tight-knit clan.

Thirty-six hours after his son’s disappearance, James Kilroy left his house in Santa Fe, Texas, and drove 380 miles south to the Sheriff’s Department in Brownsville. He pledged not to leave until his son was found. In the days that followed he all but set up residence in the department, continually grilling the detectives and Customs Agents working the case about the latest developments, while Helen Kilroy and a group of concerned neighbors manned the phones back home. When not at the department, James was passing out homemade fliers on the international bridge between Brownsville and Matamoros, within easy sight of where Little Serafin Hernandez had lured Mark into his pickup truck. Despite the punishing heat, James would prowl the bridge for hours, haggard but determined, thrusting his fliers into the hands of the tourists and locals that swarmed around him. He offered a $5,000 reward for any information on Mark; the Brownsville business community chipped in another $10,000. At the end of each day, James would call home to Helen and say, “Good news. They didn’t find a body.” After a while, Helen couldn’t endure the excruciating wait, and she joined her husband in Brownsville to continue the search. Together with volunteers, they blanketed the area with more than 20,000 flyers.

The media descended on the scene as well, as the case spawned headlines throughout the country and became a staple on the evening news. The massive media coverage prompted a deluge of phone tips to the investigators, but none of the tips turned up anything useful. A special America’s Most Wanted segment on Kilroy’s disappearance spurred hundreds of additional and equally dead-end calls.

By the beginning of April, the investigators working the case hadn’t uncovered a single helpful lead. It was as if Mark Kilroy had simply vanished into the air. Only James and Helen Kilroy remained unwavering in their conviction that their son would be found alive. Deeply religious, the two parents drew daily solace from their tight-knit community of fellow churchgoers back home, and from the network of churches in Brownsville and Matamoros whose attendees were offering prayers and donating money to the Kilroys’ efforts.

“I feel he’s going to come back to us,” Helen Kilroy told one of the myriad journalists who interviewed her. “We don’t have any anger. We just want Mark back. With everyone praying like this, I don’t see how the Lord can refuse us.”

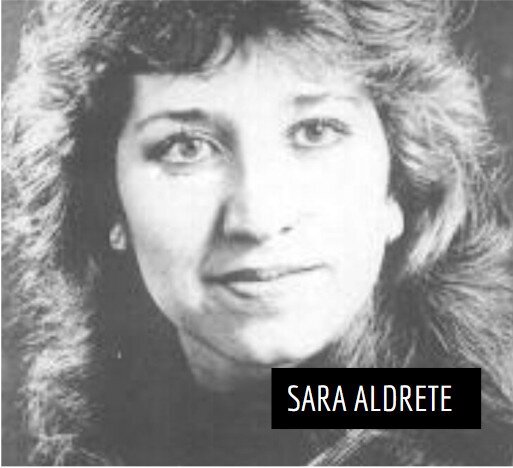

Sara Aldrete was driving her father’s green Impala through the sticky Matamoros afternoon when a shiny new Lincoln Crown Victoria with Florida plates abruptly cut her off in traffic. Aldrete was an exceptionally tall, thin Matamoros native with curly black hair, bright eyes, and a prominent nose. Married and divorced at a young age, the 24-year-old Aldrete was a physical education major at Texas Southmost Community College across the border in Brownsville, where she excelled equally at academics and athletics. Her friendliness, intelligence, and diligence made her a star among faculty and students alike.

When the Lincoln Crown Victoria cut her off, Aldrete’s initial anger dissipated the moment the car’s passenger — a graceful, darkly handsome man, impeccably dressed — stepped from his door to apologize. “Call me Adolfo,” the man told her, inviting her to chat inside his air-conditioned vehicle. Introducing himself as a Cuban-American who did business with Colombians — Aldrete knew what that implied — the suave stranger spent the next hour regaling Aldrete with stories of international travel and fabulous wealth. Aldrete felt an instant chemistry with the confident, charming man, despite his enigmatic nature. He was certainly a refreshing distraction from the memories of her failed marriage and from the dusty, well-worn streets of her glamourless hometown.

Though Aldrete didn’t know it, the meeting had been anything but accidental. Aldrete’s current boyfriend was a local drug dealer named Gilberto Sosa, a mid-level associate of the town’s powerful Hernandez drug smuggling family. Constanzo had carefully planned his “accidental” meeting with Aldrete because he wanted her connection, via her boyfriend, to the Hernandezes. Over the next weeks he played the enchanting suitor, bringing Aldrete into his confidence, declaring that he loved her, taking her to bed. He also introduced her to his religion, filling Aldrete’s mind with grand pronouncements regarding the exalted existence that Palo Mayombe provided. To Aldrete, who for years had been eager to escape the dreary confines of her life in Matamoros, Constanzo appeared to be a savior, and Palo Mayombe her destiny. By the end of the summer Aldrete had become a wholehearted convert to Constanzo’s burgeoning cult. In private Constanzo called her La Madrina, the “godmother.” He also used her connections to broker his first meeting with the Hernandezes.

Constanzo told the Hernandezes that his black magic could protect them from their rivals and lift them to dizzying new heights of fortune and influence. Ordering the family to call him El Padrino, he introduced them to the tenets of his practice: prayers to the deity Eleggua, the ritual cigar smoke and rum, the flaming cauldrons and candles, the killing of roosters and goats. Sacrifice was essential: the taking of another life brought vitality to one’s own.

Constanzo also took charge of the family’s drug business in Matamoros, Mexico City, and Miami, using the guise of his supernatural clairvoyance to manage its operations. And indeed his magic appeared to work: the group’s shipments and profits grew ever larger, with law enforcement seemingly helpless to intervene. The police always arrived too late or too early to catch a delivery or payment in progress. What the Hernandezes didn’t know is that Constanzo’s faultless decision-making wasn’t guided by magic, but by insider tips he received from the high-placed law enforcement professionals he counted among his followers.

Soon Constanzo introduced a change in the rituals he presented to the Hernandezes. Animal blood was good, he told the family, but its strength had limits. Real dominance, real invincibility, would come only from the slaughter of human beings.

Constanzo introduced the Hernandezes to the practice of human sacrifice by focusing first on their rival drug dealers. What better way to gain power, he preached, than by physically and spiritually subsuming those who opposed you? Accordingly, the family began their killing spree by shooting several competitors.

But though these sacrifices proved useful in expanding the gang’s business, they were less than satisfying for Constanzo. To truly gratify the Palo Mayombe gods, the death of one’s victim needed to be slow and excruciating. This would allow their souls to be transferred into one’s own. Constanzo demonstrated for the Hernandezes the kind of sacrifice he had in mind by torturing a transvestite acquaintance named Ramon Esquivel before killing him. Constanzo proved equally merciless with disciples who violated his rigid rules of behavior. A cocaine-snorting follower named Jorge Gomez, who ignored Constanzo’s ban on using drugs, met the same ghastly end as Ramon Esquivel.

The greater Constanzo’s brutality, the more the Hernandez’s business seemed to thrive. The family wholeheartedly embraced El Padrino’s insistent preaching that his witchcraft was the driving force behind their revival. Along with Aldrete, devotee Omar Ochoa, and bodyguard Martin Quintana, the Hernandezes now formed the core of Constanzo’s cult. As always, Constanzo’s words, combined with his remarkable charisma, had induced total cooperation in his followers.

One night, Constanzo’s brutality failed to achieve its desired results when the chosen victim, a hardened veteran of the region’s drug wars, remained maddeningly silent, refusing to scream as Constanzo tortured him. His mute rebellion denied Constanzo the power of owning his soul. Enraged, Constanzo ordered the Hernandezes to bring him an American college student, someone blonde and yielding. An American, Constanzo knew, would be weak.

Little Serafin Hernandez and an associate immediately jumped into their truck and headed for Matamoros, which was flooded with U.S. college students on their yearly spring break. How naïve these revelers were, Constanzo thought, to believe their youth rendered them invincible, to assume it would protect them from the devil in human form.

Later that night, a panicked Mark Kilroy lay curled in the back of a pickup truck parked at the Hernandez ranch, his eyes blindfolded, his hands and feet bound with duct tape. When he pleaded with Little Serafin to tell him what was going on, the stumpy gang member answered reassuringly: “Nothing’s going to happen. Everything’s okay.” Giving Kilroy some crackers and water, Little Serafin assured him that he would be released unharmed.

It was 3 a.m. Leaving Kilroy in the truck, a tired but happy Little Serafin went home and fell into an easy sleep.

Nine hours later, a trembling, terrified Kilroy, his blindfold removed, was dragged from the back of the truck through a trash-strewn clearing dotted with withered-looking cows. Next to a corral stood a decrepit tarpaper shack with boarded windows and a collapsing roof. Kilroy was pushed inside. The thick, putrid reek of cigar smoke, rum, and rotting flesh enveloped the room. Candles burned on the building’s blood-soaked floor, illuminating four small kettles filled with rotting animal parts, human hair, coins, twigs, and gold coins. A bloody machete and hammer lay to the side, along with a thick roll of electrician’s tape. Nearly every inch of the shack’s walls was black with smeared blood and crawling with flies.

In the middle of the shack stood a large iron cauldron filled with a liquid, pulpy stew of human bones, railroad spikes, spiders, sticks, and a dead black cat. This was a nganga, the bubbling iron pot that forms a core part of Palo Mayombe rituals. El Padrino waited next to the cauldron, a beatific smile on his face, a machete in his hand. Kilroy was stripped and forced to his knees in front of the beaming sorcerer.

“Welcome to the house of the devil,” Constanzo intoned.

Then the true horror began.

Constanzo’s machete flashed through the air. Chanting above the muffled screams that struggled from Kilroy’s taped mouth, Constanzo offered prayers to the gods and implored the dead for ultimate supremacy. As he prayed, he mutilated Kilroy’s body. Amid this swirl of violence, Constanzo swigged from a bottle of raw rum, spewing the alcohol over Kilroy and into the nganga.

Bursting with the sexual thrill of his ritual, Constanzo raised his machete in the air and brought it down on Kilroy’s skull.

After the harsh interrogation, Comandante Benitez and his officers drove the Hernandezes from prison back to Rancho Santa Elena to gather evidence. With Little Serafin as guide, the convoy of trucks skirted a massive cornfield before coming to a stop next to a shack. A cardboard box filled with votive candles sagged against the structure.

As Benitez stepped from the lead truck, his nostrils were assaulted by an odor so revolting that he and his agents stepped backwards as if physically struck. Gagging and retching, they broke open the shack’s door and forced Little Serafin inside. The remnants of slaughter were everywhere. Two bloody wires with wrist-sized loops at the ends hung from a rafter. These were for draining the blood from victims, Little Serafin explained. An oil drum, used for boiling victims, stood off to one side.

The most appalling sight sat smack in the shed’s center: Constanzo’s nganga. A fleshy black mass speckled with bone and hair floated in the cauldron’s center. Even some of the most jaded agents stumbled out the door, heaving.

Little Serafin pointed at the nganga. “This is where the spirits live,” he said proudly. The fleshy mass in the center was Mark Kilroy’s brain.

Announcing this, Little Serafin gave a beatific smile. An enraged federale yanked a thick stick from the pot and bashed Little Serafin over the head in response.

The scene outside was just as grisly. Little Serafin showed the federales a series of shallow graves beyond the shack holding the remains of at least fifteen male victims of the gang. The victims had been mutilated, their flesh burned, their limbs and testicles sliced off, their hearts ripped from their chests.

A metal wire protruded from one of the graves. That was Mark Kilroy’s grave, Little Serafin said. The wire was attached to Kilroy’s spinal column; once his body had decomposed, his spine would be wrenched from the ground and turned into necklaces for the gang. Aldrete, Uncle Elio, and the others already wore such trophies, Little Serafin added.

Benitez and his agents aimed their machine guns at the still-grinning smuggler. “Dig,” Benitez ordered. For the next several hours, at gunpoint, Little Serafin and the Hernandezes labored to dig up bodies from the hard-packed soil. Despite the punishing heat and dust, the infuriated federales refused to give the men water. Remarkably, even as they worked, the Hernandezes continued to believe that Constanzo’s magic would protect them from further punishment. “You can’t hold us,” Little Serafin bragged to Benitez as he dug. But even magic couldn’t keep Little Serafin from repeatedly being sick as the smell of rotting corpses enveloped him.

James and Helen Kilroy made a pilgrimage to Saint Luke Catholic Church in Brownsville, where they had sought daily refuge during the weeks-long search. The grieving parents were now joined by one thousand fellow mourners to say a final goodbye. Standing at the lectern with a picture of Mark behind her, Helen spoke, remarkably, of forgiveness. She told the assemblage that her son was in a better place now, and that during his twelve hours in the back of Little Serafin’s pickup truck, he’d had abundant time to pray and seek solace from God. He had found peace with himself.

“I ask you to pray for the people who have done these things,” Helen serenely told the crowd. “Pray that the Lord will enter their hearts and they will know what they have done is wrong. Pray that they will know there is love.”

Benitez was not in the mood for forgiveness. His eyes were puffy and red, his skin mottled, his hair a greasy, matted mess. In the four days since he’d discovered the bodies at Rancho Santa Elena, he’d slept a total of three hours. He felt besieged on all sides. In Matamoros, corrupt government officials and local police were stymieing his investigation of Constanzo’s whereabouts in an attempt to protect potentially compromised members of Mexico’s elite and to deflect blame for Constanzo’s killings onto the United States. In Brownsville, U.S. representatives and sheriffs were attempting to take credit for Benitez’s success.

Meanwhile, in prison, Little Serafin, Uncle Elio, and the other captured gang members continued to sneer at Benitez. El Padrino would rescue them soon, they mocked. The threat of violence from the federales only made them snigger harder. Didn’t Benitez know they were under magical protection? Elio, in particular, remained thoroughly unrepentant. The stumpy gang member might as well have been lounging on a beach for all the worry he exhibited.

Finally, after so many hours of fruitless interrogations, Benitez snapped. Jerking Elio by the handcuffs, twisting the metal so hard that Elio’s wrists began to bleed, the comandante dragged the smirking prisoner into the oily dirt parking lot out back. “Bring me the Horn of the Goat!” he shouted at one of his agents.

The agent obligingly handed Benitez one of the AK-47 assault rifles recovered from the raid at the Hernandezes. Benitez pointed the barrel right between Elio’s eyes.

“Fuck your mother,” Elio scoffed. “Your bullets can’t hurt me.”

Jerking the barrel just to the left of Elio’s head, a livid Benitez fired three quick shots into the ground. Elio twisted in panic, his eardrums roaring from the blast.

“Now what do you think of these bullets?” Benitez barked.

Elio’s cockiness evaporated. In a matter of minutes he gave Benitez the locations of two of Constanzo’s residences in Mexico City. “It is where he has his rooms of the dead,” he said.

Early on the afternoon of May 6, with memories of the previous day’s Cinco de Mayo celebration still buzzing in the air, a small group of police officers fanned out throughout the historic Cuauhtemoc neighborhood in the heart of Mexico City. The search of Constanzo’s two residences in the city triggered by Elio’s confession had turned up empty. El Padrino and his followers had long since fled. Now the federales were following up on a report that a pale, towering woman resembling Sara Aldrete had been spotted shopping in the area. There was also news from a local supermarket that, in a highly unusual occurrence, a young man with a dyed punk hairdo had attempted to buy groceries with a U.S. $100 bill. Though the tip was considered a longshot, the federales were desperate, and two teams of plainclothes detectives dutifully arrived to stake out the market.

Near the store, kitty-corner from 19 Rio Sena, one of the detectives, Carlos Padilla Torres, stopped to examine an old car that appeared to have been abandoned at the curb. It would have been a cursory matter, quickly forgotten, but the car, though Padilla Torres didn’t know it, was parked directly across the street from the grubby fourth-floor apartment where Constanzo and his followers had been camped out for the past several days.

As Padilla Torres peered in the car, Constanzo, in his apartment, pulled back the living room curtain to examine the street below. He was scanning for signs of danger, an action he had been repeating obsessively since going into hiding. If he had been in a sharper state, he might have realized the detective was performing a routine duty. But Constanzo was exhausted after weeks on the run. In his apocalyptic mindset, he thought the end had arrived.

“They’re here!” he yelled. “They’ve come for us! This is it!” Aldrete, Rodriguez, Ochoa, and Constanzo’s maniacal hit man, a 22-year-old Mexican nicknamed El Duby, jumped to their feet, only to watch dumbstruck as Constanzo thrust his Uzi submachine gun out the window and began firing wildly.

Down below, the uncomprehending Detective Padilla Torres thought for a moment that a group of children was throwing rocks at the car. Then he felt a bullet rip his chest, and he frantically dove behind the car as the vehicle’s windows exploded. Vendors and passersby on the street ran for cover or ducked behind other vehicles as a hailstorm of bullets rained from above.

“You bastards can’t get me!” Constanzo cried as he continued shooting. “I’ll see you all in hell!” He unleashed a prayer to the Palo Mayombe god Eleggua for divine intervention. Behind him, Aldrete and Ochoa begged for escape, desperate to run from the apartment while there was still time. El Duby, ever submissive to his master, dashed from room to room, gathering fresh magazines for Constanzo and loading empty ones with bullets. Quintana joined Constanzo at the window, uselessly firing a shotgun into the air. “We’ll kill them all!” Constanzo shouted. He aimed his machine gun at a large propane tank across the way in a vain attempt to explode it.

In the hectic minutes that followed, backup teams of federales joined Detective Padilla Torres on the street, returning fire whenever Constanzo paused to reload. As reinforcements arrived, the officers pulled on flak jackets, evacuated trapped pedestrians, and set up barricades on the increasingly shell-ridden street.

For nearly an hour the chaotic gun battle raged, until Constanzo began to run low on ammunition. Realizing escape was impossible, he became strangely subdued, almost peaceful. He had worshiped the power of death since he was a child; now it was almost upon him. “Remember our pact,” he said to Quintana, grabbing his hand. “We’ll die now, but we will be born again.” Turning on his heels, he led Quintana and El Duby into the back bedroom.

Wrapping an arm around Quintana, Constanzo placed his submachine gun in El Duby’s hands. “Do it,” he ordered. El Duby — the same hardened assassin who just a few weeks earlier had gleefully chopped Mark Kilroy’s body into pieces after Constanzo had murdered him — numbly shook his head: “No, Padrino, I don’t want to kill you.”

“Do it,” Constanzo ordered, “or I will make things tough on you in hell.” He reached out and slapped El Duby twice in the face.

With tears rolling down his cheeks, El Duby closed his eyes and pulled the trigger.

In the living room, Aldrete heard the burst of bullets. “Adolfo!” she cried, tears springing from her eyes. She felt a paralyzing wave of pain, love, and rage. She also, amidst this wash of emotions, felt an unexpected twinge of relief. Glancing at El Duby, who had stumbled dazedly out of the bedroom, she suddenly realized what she had to do.

Flinging open the front door, Aldrete sprinted into the hallway and half-tumbled down the staircase to the lobby. “Don’t shoot, I’m coming out,” she yelled as she ran into the street. “I’ve escaped!” She ran straight into the arms of a muscular federale, who spun her around and pinned her wrists together. “Thank God,” Aldrete said, adopting a guise of helpless innocence. “I’m saved.” The startled federale, who had expected a violent, demented cultist, wasn’t sure how to respond.

“I’ve been through hell since they kidnapped me,” Aldrete told him, playing the victim. “I thought I’d never get away. I’m so glad you came.” The federale surprised himself by reaching out to comfort her.

As Aldrete continued spinning her ruse, a heavily armed team of agents, clad in jumpsuits and bulletproof vests, raced up the four flights of stairs to the apartment. When they reached the back bedroom, they found two bullet-riddled bodies sprawled on the closet floor. The walls above were sprayed with blood. One of the bodies was a dark-skinned Mexican man with dyed reddish hair. The other, taller man was light-skinned and sported a trim mustache, blue and white shorts, and a trim American-style haircut. He looked so well groomed that he could have stepped from a 1950s sitcom. The agents could hardly believe this was the sadistic cult leader they had been chasing.

“Do you think it’s really Constanzo?” one of the federales asked, wary of a setup.

“It better be him,” another responded. “It just better be.”

Ona brilliantly sunny Sunday morning, as winds from the coast swept across the dust-choked grounds of the now deserted Rancho Santa Elena, Comandante Benitez, wearing a beige polyester leisure suit and black baseball hat, stepped down from his truck. He was accompanied by several of his officers, two U.S. experts on cult violence, and a curandero — a white witch.

As Benitez barked orders, the curandero, dressed in casual clothes and Nike tennis shoes, hauled a can of gasoline into the tiny shack where Constanzo’s ghastly nganga still sat. Moving quickly, the curandero splashed gasoline all over the walls and floor, then dashed outside and poured more gasoline around the entrance. When he finished, he signaled a waiting federale, who flung a burning torch into the shack. Within moments, the building erupted in flames, the fire whipped by heavy winds, black smoke thickening the air.

The curandero, rushing close to the inferno, hurled a five-pound sack of salt into the flames, and then another, chanting a series of purifying prayers as he toiled. He continued flinging salt and praying until only a smoldering pile of embers lay on the ground.

Then the curandero, wielding a two-by-four plank in his hands, sprinted forward and struck the nganga four times. He nodded with satisfaction. The evil spirits were nearly vanquished. At his signal, Benitez’s men dumped the nganga on its side and lit its gruesome contents on fire. When the flames died out, the curandero called the group to his side and bathed their hands with holy water.

Benitez, his body coiled with tension from the strain of the previous weeks, felt himself beginning to relax. He inhaled a breath of crisp, rich air. The ranch, so recently soiled with human slaughter, had been cleansed. Aldrete and the surviving cult members would spend years in prison. Sacred spirits had returned to the Rio Grande Valley.

At Benitez’s side, the curandero, his eyes triumphant and glistening, lifted a white dove from a cardboard box. For a few brief moments the dove lay unmoving in the curandero’s hands. Then it unfurled its wings and fluttered off into the morning sky.

COREY MEAD is a professor of English and author of three nonfiction books: The Lost Pilots, Angelic Music, and War Play.