America’s first policewoman protects the unprotected in a Los Angeles brewing with danger. Mocked and hampered at every turn, and paid 73 cents on the dollar, Alice Wells tracks a missing heiress to an insidious cult — and transforms policing.

For three months the world searched for Lily Maud Allen, who had vanished from her London home in November 1910. Some looking for her were convinced she was actually the mistress — and probable accomplice — of a man convicted of poisoning his wife. Others who hunted for her believed she was kidnapped by religious fanatics. Conniving seductress, or helpless victim: women were often put into one box or the other.

The following month, Allen reappeared on the other side of the Atlantic, arriving aboard the ocean liner St. Paul at Ellis Island. There she was detained by U.S. immigration officials at the request of British diplomats but slipped from their custody and once again was in the wind. Dockhands reported seeing her whisked away by men and women wearing dour, dark-blue uniforms. Their caps bore, in silver gilt, the words “Pillar of Fire.”

On February 4, 1911, Los Angeles police chief Charles Sebastian received an urgent letter from his counterpart in Denver. Rumor had it the missing young woman had traveled west from New York under an assumed name, Ruth Allen. The Pillar of Fire, a religious sect, had been founded ten years prior in Denver, but the city’s police chief couldn’t find her there. His message to Sebastian suggested that she might instead be hiding in the City of Angels, where the Pillar of Fire had burned strong for years.

It was a delicate matter that called for equal parts compassion and toughness. The police, after all, wouldn’t get anywhere simply demanding the young woman’s whereabouts; they needed to infiltrate this strange cult.

Chief Sebastian knew just who should handle this case. The officer moved with ease through religious circles, could blend in among the cult’s mostly female ranks, and had already caused holy hell by petitioning to join the police. Her name was Alice Stebbins Wells. Widely regarded as America’s first female police officer, no one could have imagined she would be exactly what the city needed.

When Alice first sat down with Los Angeles Mayor George Alexander on June 8, 1910, he sized her up, all 5-foot 2-inch, 120-pounds of her. “How can you be a police officer?” he asked in his Scottish brogue. The Civil War veteran was a fossil of the nineteenth century, yet he was the man whose support Alice needed most to overthrow law and tradition that reached back generations.

Alice, 36, explained that she didn’t aspire to use physical force, nor did she particularly want to make arrests. “I want to keep people from needing to be arrested.”

Alice pointed out that young men and women were visiting “undesirable cafes” and places of amusement in increasing numbers. “A woman could often stop that sort of thing,” she told the mayor, “where a man would only arouse antagonism. A woman knows better how to deal with situations where a girl’s welfare is concerned.”

Across America, female suspects suffered beatings and worse at the hands of arresting officers. The newspapers were full of such stories. The previous February, a German immigrant prostitute was battered during a routine arrest at a downtown Los Angeles barber shop that doubled as a boarding house. Rape was not unheard of. If the circumstances called for taking a woman into custody, Alice believed, female officers could do far better.

The mayor pointed out that no ordinance permitted a woman on the police force.

“I know that, but this,” she said, gesturing to a document she brought with her, “is the first step toward securing one.”

Alice had not marched into the red sandstone City Hall that day empty-handed. For months, she had courted leading citizens to her cause, eventually persuading 35 of them, preachers and bankers, rabbis and temperance activists, to affix their names to a petition demanding that a woman be allowed to serve as police officer.

She also brought with her a history of social work and gender breakthroughs. After high school, Kansas-born Alice Bessie Stebbins had moved to Chicago to work the World’s Columbian Exposition. While there, she was surrounded by a terrifying mystery: at least 9 but possibly as many as 200 young women like her, drawn to the Windy City by the fair, went missing. By the time the truth was revealed — the missing women had been murdered and cremated by one of American history’s most notorious serial killers, the charming doctor H. H. Holmes — Alice had begun a lifelong devotion to the welfare of vulnerable urban populations.

“Across America, female suspects suffered beatings and worse at the hands of arresting officers.”

Working from settlement houses within Chicago’s working-class neighborhoods, she and other volunteers dispensed childcare, medicine, education, and other badly needed services to the Windy City’s poor. The next stop was Brooklyn’s famously progressive Plymouth Church. After apprenticing for a minister, she graduated from seminary, broke barriers preaching from the pulpit, and led her own congregation back in the Midwest. There she met Frank Wells, a farmer from Wisconsin, and on December 23, 1905, the couple married. She resigned from the ministry to raise a family — Alice and Frank had three children — and around 1909 a business opportunity for Frank landed the entire Wells family in California.

Lured by sunny weather and sunnier ambitions, newcomers from the Midwest and eastern U.S. streamed into Los Angeles. So many came, in fact, that between 1900 and 1909 the city’s population tripled to 300,000. To house them all, the city was, by the decade’s close, issuing an average of 19 new building permits every day. Open countryside still separated Los Angeles from its satellite settlements — Hollywood, Santa Monica, Venice, Pasadena, and the newly subdivided burgh of Beverly Hills — but not for long, as the city began to spill out of its historic downtown along a web of trolley lines. There were even plans afoot to open up the wheat fields of the San Fernando Valley for suburban settlement, once Owens River water arrived by way of the city’s $23-million aqueduct. Los Angeles, built on the foundations of an Old West town, rife with gambling prostitution, was quickly taking on the appearance of an overgrown prairie town. Cultures and standards of morality clashed.

After Alice laid out her vision to Mayor Alexander, he warmed to the radical idea of a female officer. It didn’t hurt that his approval would cultivate support from the influential names on her petition. “It looks to me like a means of doing much good,” he told a reporter from the Los Angeles Times later that day. “Many young girls and boys are started on evil lives … and a woman could easily discover these things where a uniformed policeman could not.”

But when the police commission met a few days later to consider Alice’s petition, police chief Alexander Galloway objected that the officer might take her orders from the women’s clubs, churches, and charitable organizations that launched the petition. In other words, she would be a Trojan Horse for subversive women’s interests. He wanted a promise that she would report directly to him and be subject to the department’s rules and regulations.

A commissioner answered: “I can assure you she will be directly under the orders of the police commission and treated as any patrolman in the department.”

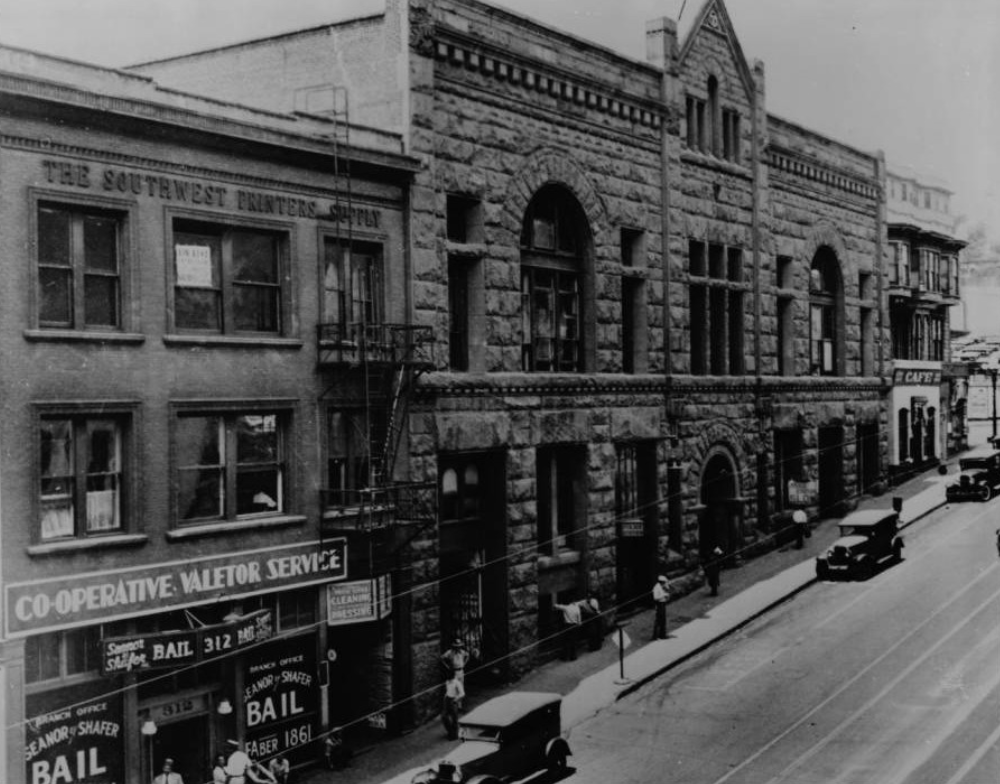

Los Angeles Police Headquarters. Photo courtesy of University of Southern California & California Historical Society.

The issue of her salary then came up. Never mind that the commission had just confirmed that the policewoman would be a full officer, treated the same as the patrolmen who earned $102 a month. Chief Galloway proposed, and the commission agreed, to pay the policewoman $75.

Sworn in on September 13, 1910, Alice made sure to set the right tone when she spoke to reporters. “This is serious work, and I do hope the newspapers will not try to make fun of it,” she said.

The press didn’t oblige. The Los Angeles Times referred to her as “Officer Wells — maybe it should be ‘Officeress Wells’” and joked that her police badge, “pinned over her heart,…[hid] as much of her little self as a breastplate would.” Out-of-town publications joined in on the fun. Cartoonists across the country disregarded Alice’s slight, slender figure and caricatured her as a big, bony, muscular woman. The Cleveland Plain Dealer took a different tack, declaring that Alice “should be properly chaperoned” — by a male officer, presumably. The San Francisco Chronicle’s banner headline read: “Skirts Among Police — This May Come Next.”

In Richmond, the Times Dispatch gleefully recorded, verbatim, the meltdown its city’s police chief suffered when he heard of Alice’s appointment. “When I was a youngster,” Major Louis Werner exclaimed, “the women used to stay at home and mind the babies, and there was always quite a big crop of babies in those days.”

Werner added a dark warning:

“Mrs. Alice Stebbins Wells will soon get tired of twaddling with that stick of hers, and she’ll run into a proposition one of these nights that will take all the curl out of her marcel waves.”

The disappearance of Lily Maud Allen was only the latest in a series of troubling events connected to the Pillar of Fire sect, led by a woman who preached radical equality of the sexes. Alma Bridwell White —48, tall and heavyset, with sunken eyes and grey hair — was a study in contradictions. She originally founded the Pillar of Fire in Denver, Colorado, after a group of Methodist ministers admonished her that a woman’s place was at home. She later reflected: “Men had held the reins of government in the church for nearly two thousand years, and it was time for a change.”

On the surface, the Pillar of Fire might have seemed a minor civic nuisance to most of Alice’s fellow Angelenos, no more dangerous than the food faddists and snake-oil salesmen who soapboxed in Central Park. Holy Jumpers, as its followers were called for their convulsive stomping, could be seen going door to door or standing on street corners in dour uniforms, selling gospel literature, like any number of fringe religious groups. Their views on modern life were considered amusing. According to one news report, Jumpers were “opposed to dancing, drinking, smoking, theatre-going, divorce, card-playing, novel reading, pretty clothes, rouge pots, Christmas trees, taxi-cabs, joy rides, hobble-skirts, peach basket hats, poodle dogs, massage parlors, manicure maids, chorus ladies, straight front corsets, artificial teeth, make-believe hips and busts, and highly seasoned mince pies” — all works of the devil.

If not the devil, evil certainly lurked in Southern California as the first decade of the twentieth century drew to a close. Outsiders flooded in, and a few brought with them a violence that shocked even Los Angeles, a city whose bloody frontier days were still within living memory. The October 1, 1910, dynamiting of the anti-union Los Angeles Times’ headquarters by socialists — the original “crime of the century” — claimed 21 lives and stoked fears of an all-out war between labor and capital. The Boyle Heights Fiend stalked the city’s Eastside, sexually assaulting at least a dozen women, sometimes tying up their husbands or boyfriends and forcing them to watch. In May 1909, a man abducted nine-year-old Anna Poltera as she was walking home from school near Los Feliz. Several days later her body was discovered in a thicket of mustard plants in Griffith Park, her throat sliced so deeply as to almost sever her head. Her killer was never found.

White claimed hers was an innocent Christian revival group, intent on reintroducing true Methodism to cities across the English-speaking world. The public suspected something sinister. The group made enemies wherever its tents sprang up.

Alma White attracted the attention of the Los Angeles Police Department soon after she arrived in town in spring of 1904 as leader of the Burning Bush movement, a forerunner to the Pillar of Fire. A cacophony of noise emerging from 315 South Olive Street — shouting, shrieking, moaning, and wailing, all set to the incessant thump of a bass drum — announced the arrival of this bizarre new faction. Noise continued day and night and was so loud, neighbors complained they couldn’t even hear the ringing of the steel cables that pulled the nearby Angels Flight funicular up Bunker Hill’s eastern slope. When police officers arrived on May 29, however, no one was willing to swear out a warrant against White and her fellow leaders, who included her husband, “Elder” Kent White, and “Brother” William Edward Shepard. The cult projected an aura of intimidation, and the police had no choice but to let them be.

On the outskirts of the city’s banking district, White and her followers soon raised a revival tent — the kind encountered in rural America — and the din continued unabated. For weeks hundreds of curious Angelenos packed themselves beneath the canvas. In a typical scene, witnessed by a Los Angeles Times reporter, White strutted — one observer likened her clumsy movement to the “gamboling of an elephant” — across a platform that elevated her from the sawdust floor. She singled out a face in the crowd. “Stand up there!” she boomed. “You are the one, I seen you last night. Hey, you fellow over there. I got you spotted, stand up!” A 16-year-old golden-haired boy in blue overalls stepped forward, fell to his knees at the platform, and cried convulsively as men and women placed their hands on his shaking body, shouting “Amen” and “Glory Hallelujah.” The boy wailed with all his lungs for ten minutes, beating his hands on a bench until they were red and bruised. Eventually, he collapsed from exhaustion. Later, as the boy lay unmoving on the sawdust, White’s husband informed the Times reporter matter-of-factly that “it is the spirit of God possessing his soul.”

In his report, the Times journalist suggested that White and the other leaders of her movement were unleashing a form of mass hypnosis. Whispers spread about strange sacrificial rites, in which cult members tossed their cherished possessions into a bonfire. There was even hushed talk of human sacrifice.

By late 1909, White cast her net wider, leading a delegation of 20 missionaries across the Atlantic to London. Soon after, Lily Maud Allen wandered into one of the revival meetings in Bedford Chapel, Camden Town, and heard White preaching. “I knew it was the right thing for me,” the recruit later recalled. Announcing her intention to enlist as a Pillar of Fire missionary, her father forbade it. When she sailed across the Atlantic anyway, she was playing out an already familiar, if dangerous, pattern where dreamers fell under White’s spell, leaving panic and desperation in their wake. Only a few years earlier, Angelo Vitagliano of Los Angeles had summoned police when his sixteen-year-old daughter Annie disappeared into the Burning Bush. Now, a frantic J. C. Allen drew upon his connections as a prominent London merchant. He cabled the British consul in New York and alerted the American immigration authorities, explaining that his daughter was a minor and ailing from tuberculosis. Allen’s distressed pleas launched a dragnet that mobilized law enforcement agencies on two continents.

After splitting with the Burning Bush movement and emerging as the head of her own organization, the Pillar of Fire, Alma White received the title of superintendent for life. White ruled with an iron fist: “My word is final.” If White sensed that the devil had deceived one of her followers — if a recruit hinted through word or action at independence — she would make them the target of a “prayer siege.” “People,” White would say, “are like horses — no good until their spirit is broken.” She forbade medicine and doctors; the sick or injured received prayers or had their bodies anointed with oil. And she demanded total commitment from her followers. “There is only one way to join us,” she said. “That is to turn in all your money and live with us.” Helen Swarth, a former Jumper who escaped the Pillar of Fire and later penned a tell-all memoir, described White as someone who sought “to absorb the personality of the convert into…herself, leaving nothing but a shell devoid of originality or initiative.”

Upon initiation into the group, Elizabeth Northcutt of Los Angeles, once described as a loving mother and wife, disowned her son, telling her husband the boy was “unsaved,” and drained her family’s bank account. She set out to become “a shining light.” A year later Northcutt turned up raving mad and emaciated. Eventually, her husband had her committed to an asylum. In Connecticut, 22-year-old Leslie Galloway abruptly left his job as a bookkeeper for a local contracting firm, renounced his membership in the Methodist church, called off his engagement to his fiancée, and signed over his life insurance policy to the Pillar of Fire. A onetime member later sued White, alleging the Pillar’s leader “acquires and maintains a hypnotic influence over the members…and keeps them in absolute subjection by threats that through her prayers she will call down flames of fire upon them.”

By the end of the decade, the Pillar of Fire could claim 20,000 souls, and its coffers overflowed with the life savings of its converts. White and her collaborators could fund aggressive methods of acquiring new believers. When Lily Maud Allen expressed a desire to join the Pillar of Fire, White leapt into action. She enlisted one of her young missionaries and smuggled Allen onto a steamship. Heightening the intrigue, Allen was swarmed by reporters because of her resemblance to Ethel Le Neve — a trim, doe-eyed woman whose photo graced newspapers around the world when it turned out she was the mistress to a convicted wife-killer.

In London, the authorities, searching for clues into Allen’s whereabouts, pressured White and the Pillar of Fire out of Bedford Chapel.

When the Los Angeles police got intelligence that the young Englishwoman could be in their jurisdiction, the chief immediately summoned Alice to his office.

“Mrs. Wells,” he said, “here is your first big case.”

“I am ready, chief.”

Locating the Pillar of Fire was not the problem: The cult was listed in the city directory. But Alice must have been shocked when she realized the Pillar of Fire now headquartered itself in the city’s booming south-central district, at 1185 E. 36th Street — no more than a five-minute walk from her own house, which she shared with Frank and their children, Ramona, Raymond, and Gardner.

On this cool, rainy Saturday, Alice stepped up to the cult’s address. She could barely see the building through the dense vegetation that screened the compound from prying eyes. But it was a large lot, and there were rustic remnants of the property’s former life as a family farm: chicken coops, outhouses, grazing cattle. A windmill once towered over the grounds, too, but it burned down shortly after the cult took possession.

If Alice and Alma White ever crossed paths in person, the most likely occasion would have been one of White’s public talks in Los Angeles on, of all things, the “Emancipation of Women.” Safe to say, Alice would have found no humor in the irony, or in the recruitment tactics disguised as lectures. White was billed as the “Greatest Woman Preacher.” Face to face, White would have dwarfed Alice. She was a half-foot taller and her big-boned frame barely contained her energy. By appearances, she was a lion to Alice’s kitten. But Alice’s round, blue eyes could hold court in a staring match — her steely determination was often noted by observers.

Conducting a successful investigation into White’s opaque fiefdom was another task that would allow Alice to prove her value to the police. In the five months since she was sworn in, she had stormed the fortress, as she later put it. On the day she first reported to collect her badge, Chief Galloway growled: “You wanted this job and apparently you know what you want to do. Well, go ahead and do it.”

Alice would have been aghast — but probably too polite to say anything — at the sight of pinup girls decorating the chief’s office walls. The Scottish-born Galloway was a former railroad superintendent who was not accustomed to working with women. And without any police experience, he was doubly unqualified for the job. In just a few months he would be replaced by the crusading, progressive Charles Sebastian.

As Galloway pinned the badge on her, he made light of the situation. He was “sorry to offer a woman so plain an insignia of office.” When he had “a squad of Amazons, he would ask the police commission to design a star edged with lace ruffles.”

Other men in the department didn’t know how to behave around Alice, either. When she reported to her sergeant, George Curtin, he was sitting in his shirtsleeves — inappropriate in the presence of a lady. Curtin jerked to his feet and shoved his arms into his coat sleeves as Alice approached his desk. “Either you’ll have to get used to this,” he muttered, “or we will.”

Alice prioritized having an office space that provided refuge for women in trouble. The top brass at Central Station apparently could not make room for her — or didn’t want to. Instead, the bailiff offered up his spare courtroom, its shelves stacked with court records, its floor crawling with rats, on the condition that she vacate it whenever it was needed by a judge.

Members of the public also balked at a female police officer. Soon after joining the force, Alice boarded a streetcar and flashed her Los Angeles Police star, numbered 105, to the conductor in lieu of paying a fare. In those days street railways were obligated by law to provide free rides to officers; horses were too messy, and automobiles puttered along too slowly. But the conductor refused to believe the tiny woman standing before him was a plainclothes police officer. Instead, he reprimanded her for stealing her husband’s badge and ordered her off his trolley. Alice quickly hit upon a solution. Soon, she was walking her beat with a new Los Angeles Police star, engraved with the word “Policewoman” to prevent any confusion. Fittingly, the badge bore the number 1.

Some failed to recognize her authority to their own detriment. On the night of August 4, 1911, Alice was standing beneath the marquee of the Electric Theater on North Main Street when 45-year-old James Gibbons locked eyes with her — and winked. Alice crossed the street. “You winked at me?” she said, approaching him. Gibbons allegedly responded by asking if she’d like to “take a drink.” Alice, playing along, suggested they take a walk instead. “Come with me.”

And he did — down several city blocks and directly to the Central Police Station at First and Broadway, where Alice pulled back her lacy lapel to reveal a polished Los Angeles Police shield.

Book him without bail, she told the desk sergeant. The charge: disturbing the peace. In the ensuing trial before Police Judge William Frederickson, Gibbons, a father of two, admitted that he had winked at Alice but had an excuse. A nervous condition made his eyelashes twitch. Judge Frederickson ultimately ruled that Alice’s question, “You winked at me?,” was ambiguous enough to excuse Gibbons, who might have interpreted it as an invitation.

The Gibbons arrest garnered national publicity (“When You Wink at Women Use a Lot of Caution,” the Atlanta Constitution’s headline warned) and inspired the department to launch a full-scale assault against public flirts. For a time it hired slender, blonde, blue-eyed Fay Evans to walk the city streets, detailed three plainclothes officers to shadow her, and did not mind if she made eyes at passing men. Evans and her detail quickly racked up nine arrests, but their success only sparked public outcries against entrapment. “The gum-shoe flirt,” the papers dubbed Evans. After the wife of one of the offenders tracked down Evans on the street and beat her with an umbrella, the department concluded it had overreached. It cut Evans loose.

When Charles Sebastian took over as police chief in January 1911, he shadowed Alice and came away impressed. She did not just bring a new face to the force, but a new philosophy. The old ways — and the old type of policeman — could no longer serve the modern city. “Brains and character,” Alice would say later, “are now more needed than brawn.”

Staking out the Pillar of Fire headquarters, Alice’s lack of a police uniform helped her. “The less you are known the better chance you have to operate successfully,” she explained to reporters about her approach. “I will have many costumes to be used on different occasions.” For this assignment, she chose a demure outfit.

Alice navigated through the mass of shrubbery to the front porch, and knocked on the door.

In the preceding months, reporters had prodded her about details of the life of a policewoman. She was asked about carrying a gun or Billy club. “Oh now, please don’t,” she had replied. When all else failed, she could rely on her voice when in danger. “The weapon nature gave a woman was a scream and in civilized communities it is invincible.”

Entering the eerie sanctum of Alma White, Alice may have second-guessed being unarmed. There was the cult’s track record of involvement in strange cases, and the even stranger rumors. It was not so long ago that the community still frantically searched for Annie Vitagliano, the teenager who followed her mother’s footsteps into religious seclusion. On January 5, 1905, her father reported to the police that his daughter was kidnapped, and at 11 o’clock that night Patrolman Bert Parker arrived at the Burning Bush missionary house to investigate. Forcing his way inside, Patrolman Parker found young Vitagliano in a trancelike, comatose state. Brother Shepard, then in charge of the Los Angeles branch of Alma White’s cult, fought against releasing the young woman.

Alice did not shy away from danger when performing her duties. Once, a woman had asked Alice for help with her abusive husband, who would yell at her in fits of rage and throw dishes around the house. Alice tracked him down and found a formidable subject. “He was quite large enough,” she later recalled, “to have picked me up and thrown me in the street.” She confronted him anyway. After Alice was finished with one man who “used to break up the furniture,” she’d persuaded him to accompany his wife to suffrage meetings.

When the door to the cult opened, Alice could hear women chanting above the sound of dull pounding. A sharp-featured woman stepped into view.

“What do you want?” she barked.

She told the woman she was in search of “the truth,” that she wanted to join the Pillar of Fire and needed to learn more about it.

The woman studied Alice with piercing blue eyes. Several moments passed before she pressed a button on the wall by the door. The strange noises inside ceased. Alice was invited in.

Inside, the curtains were drawn and the room shrouded in darkness, except for one corner where the sunlight snuck in. The woman, taking a seat in the darkened part of the room, motioned for Alice to sit in the light.

Soon the other residents of the house emerged; as many as ten men and women shared this old farmhouse. They started into their hymns, most of which were written by Alma White herself: compositions such as “Soon I Shall Be Bloodwashed” and “The Cry of the Soul.” Alice found the hymns, whose lyrics often evoked fountains of blood, “outlandish,” but she sang along anyway.

Some thro’ the waters, some thro’ the flood, Some thro’ the fire, but all thro’ the Blood.

Singing eventually gave way to conversation. In the exchanges of the true believers, echoes of Alma White’s exhortations reverberated. “It is unreasonable and utterly impossible,” White wrote, “to support [the world’s] institutions, walk in her streets, peer in her windows, and drink of the wine cup of her fornications without being contaminated.” Holy Jumpers on every side of Alice had left their jobs and turned over all their money, real estate, and worldly possessions to the cult. The separation was meant to be absolute, which was why recruits like Lily Maud Allen were urged to sever ties with family members who refused to convert — parents, spouses, even young children.

On some level Alice had every reason to relate to the separate world Alma White had created. She understood the pain of feeling left behind by one’s community and culture, of having one’s accomplishments unappreciated, talents unutilized — generally, living a life that was overlooked, especially for married women. But White’s attempt at gender equality was a mirage. The manipulation of women’s dreams was as much a sin as the neglect of their abilities. Alice could think back to her formative time at Chicago’s World’s Fair, a hypnotic landscape of a future utopia drawing in romantics, all while women were being murdered in the shadows. Beneath the Pillar’s manufactured feelings of unity and belonging festered darkness, a dangerous sense of superiority and conflict. It would not be too much longer before White began delivering speeches praising the Ku Klux Klan, turning the Pillar of Fire into the only major religious group to publicly align itself with the hooded white supremacists.

Angels guard our pathway as we march along, Pointing to the city and its blood-washed throng.

Even though she had gone into the heart of Pillar headquarters unarmed, Alice was always prepared for a fight. She practiced martial arts. “The use of a few well chosen Jiu Jitsu tricks,” she once advised women, “will help women when sneak thieves arrive or burglars invade the home.” Despite what she told reporters, she also had at least one hidden weapon: the hatpin atop her head. “Don’t forget the trusty hat pin,” she advised, “the best weapon and most to be depended on.”

Yet Alice stood firm in her mission to avoid violent confrontation. She succeeded in persuading the followers that she was ready to join. In order to undermine Alma White, Alice embraced the part of disciple. But there was no sign of Lily Maud Allen among the chanting followers, nor in any of the chambers Alice entered.

The Jumpers served Alma White through fear, but they came to engage Alice with a different feeling: trust. By the end of that night inside the cult’s hive, Alice convinced a member to divulge Allen’s whereabouts at an 81-acre Pillar of Fire compound near Bound Brook, New Jersey. There, on a strip of land along the Delaware and Raritan Canal, some 125 members sequestered themselves from the sinful world in gloomy buildings with small windows. Allen was washing dishes and scrubbing floors, simultaneously unhappy and content with her new life. “They give the impression,” the New York Times said of the communal houses, “of being places to discipline people in.” On this campus in the coming years, White would permit burning crosses, host a Klan meeting, and set off a riot.

Alice said her goodbyes and rushed to notify the chief, who passed along word to Allen’s desperate father and the New Jersey police.

Alice’s breakthrough detective work won respect from a group that had treated her as an object of curiosity: the press. The Los Angeles Herald celebrated its policewoman locating someone “for whom sleuths of two continents searched.” The Daily Oklahoman’s headline touted a “Clever Ruse to Find Lost Girl,” and newspapers in Boston, Baltimore, Colorado Springs, and Detroit added endorsements.

As for Lily Maud Allen, in spite of Alice’s triumph, the Englishwoman ultimately remained with the Holy Jumpers. It turned out White’s camp had a secret at their disposal. Allen was not seventeen, as her father claimed. He had lied about her being a minor to spread alarm. She was actually twenty-six, and could not be removed against her will. She resurfaced some two years later in Washington, DC, as a Pillar of Fire missionary, supporting Alma White’s announcement of the Second Coming of Christ. Alice may have triumphed in the battle to track down young Allen, but White’s war was far from over.

Alice, too, had just begun, a long road of breakthroughs and challenges awaiting her. The Pillar case cemented confidence in Alice from her newest booster, Chief Sebastian. The thirty-seven-year old had cut his teeth in farming and as a streetcar conductor before entering police work, and he had no trouble embracing practical, outside-the-box thinking. That November, he paid the ultimate compliment to Alice. He made his first formal request for additional policewomen. The police commission granted it — as well as several subsequent requests. By the end of 1912, the Los Angeles Police Department passed a remarkable milestone by boasting four women officers: Alice, Aletha Gilbert, Rachel Shatto, and Nellie Tarbell.

Sebastian began calling upon departments across the country to hire women. “The natural protective instinct of woman makes her advent in the field but natural,” he explained to the San Francisco Chronicle. “We believe that women can be a valuable and harmonious addition to the police department. Mrs. Wells is our pioneer policewoman and has done satisfactory work.”

In 1913, the police chief traveled to Washington, DC, to make a forceful case to his most skeptical audience: his peers. “I can say nothing but good of women’s work in my department,” he told the Los Angeles Herald before leaving for the annual convention of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. “I shall do all in my power to convince the other chiefs of their value.” At the convention, he declared that the experiment Alice had launched three years prior had succeeded. “[Policewomen’s] worth has passed the experimental stage, and I would not, if I could, dispense with their services.” Crime abated citywide. Policewomen, per capita, were making more arrests than policemen.

Sebastian added a baritone voice to a chorus that had, until then, been mostly soprano. But he also understood that the idea of women police had no more effective advocate than the one woman who persisted beyond all odds to secure herself a badge. From September 1912 to March 1913, with the chief’s encouragement, Alice barnstormed North America as an evangelist for the policewoman movement, delivering 136 lectures to 73 cities across the continent. In the wake of her speeches, city after city would amend its laws and add a woman to the police force. She was soon able to rattle off an impressive list of cities with women officers:

Seattle, 5; Baltimore, 5; Fargo, 1; Grand Forks, 1; Rochester, 1; Syracuse, 1; Kansas City, 1; Chicago, 20; Topeka, 2; Superior, 1; Racine, 1; Aurora, 1; Denver, 1; Colorado Springs, 1; San Antonio, 1; Billingham, 1; San Francisco, 3; Salem, 1; Ottawa, 1; Toronto, 2; Birmingham, 2; South Bend, 1; Portland, 2; Tacoma, 1; Oakland, 2.

Within a few more years, Los Angeles made pay for policemen and policewoman uniform, sending Alice home every month with the same $120 as her male peers.

Now, as she boarded an Arizona-bound train for the first leg of her tour, she was trying out a new look. In her two years on the force, Alice had never worn a uniform. Representing Los Angeles across the country, she needed an outfit that reflected the dignity of her office. There was no standard-issue police uniform for women, of course, so she and Chief Sebastian designed one themselves. The result, made from a heavy English diagonal serge, roughly approximated the patrolman’s summer uniform with its golden khaki tone. The letters “L.A.P.” were embroidered on her collar, and on her head she wore a standard Stetson campaign hat. Her coat was military-trim; her skirt long and pleated.

In New Orleans, a brawny, 6’2” man who worked in the city clerk’s office approached Alice. He pleaded for a favor.

“I want to be arrested by a lady.”

—

Nathan Masters is a writer and the Emmy Award-winning host and executive producer of Lost L.A., a public television series about Los Angeles history. He manages public programs at the USC Libraries, and his work has appeared in many publications, including Los Angeles Magazine and the Los Angeles Times.

For all rights inquiries please email team@trulyadventure.us