When unexplained events terrify a young boy in 1960s New Jersey, the first purported haunting in a public housing project begins. Unearthed through original interviews and thousands of pages of archival records.

May 6, 1961

On the evening of his thirteenth birthday, Ernie Rivers, shy and serious, was playing in his bedroom in an apartment in the Felix Fuld housing development in Newark, New Jersey. Loneliness had become routine for Ernie, even on his birthday. His no-nonsense grandmother, Mabelle Clark, took care of housework in her bedroom. As she did, a glass jar on top of a dresser on the opposite end of the room crashed to the floor. Mabelle was shaken for a moment — the jar seemed to have moved by itself — then brushed it off. Ernie heard the noise from his room, but didn’t think much about it.

On May 8, two days after the glass jar incident, Ernie and his grandmother were eating in the kitchen when six punchbowl cups in the living room — connected by an open doorway to the kitchen — came off the hooks on the wall and crashed to the floor, one after the other. “That’s when it really started,” Mabelle later recalled. “Everything started smashing… Smashing — smashing — smashing.” Later that evening, several bottles in the bathroom fell to the floor and shattered. One of them, a bottle of antiseptic stored in the medicine cabinet, flew into the living room and landed on the floor. Stunned, Mabelle walked to the bathroom only to find its door closed, making the bizarre incident flatly impossible. Not knowing what else to do, she rushed into the bathroom to take down the remaining bottles, containers, and items from the medicine cabinet and place them on the floor.

When a neighbor came to their door later, Mabelle, still reeling, tried to pretend everything was normal. The three of them — Mabelle, Ernie, and neighbor Yetta Mandle — were chatting over the hum of the television in the background when a cologne bottle from the bathroom suddenly darted into the living room, zigzagging in midair (“turning a jig in the air,” as a frightened Yetta described it) before shattering against the floor. The air filled with its strong scent. Yetta also watched as a glass decanter began moving by itself to the edge of the refrigerator. She raced to catch it just before it fell. Mabelle now had no choice but to come clean to Yetta about what had been happening the last two days. As she did, a lamp in the living room spontaneously shattered, the last straw. Mabelle and Ernie fled, staying elsewhere for the night.

A statuesque, self-sufficient, and reserved woman, Mabelle did not like to draw attention to herself. She especially didn’t want the housing authority catching wind of what was going on for fear that she and her grandson would be labeled unruly, kicked out of the apartment, and probably be accused of lying. Like many metropolitan areas in the United States in the 1960s, Newark’s public housing reinforced systemic segregation, and was infested with racist practices against African American families such as theirs. But Mabelle could only hide this for so long. Their lives had just begun to be turned upside down by what would come to be called the “Project Poltergeist,” the first haunting documented by parapsychologists in a housing project in the United States.

A dark turn in the family’s history had led Ernie to live with his grandmother. Ernie’s younger years were spent in Montclair, New Jersey, with his mother and father, Ann Clark and Ernest Rivers Sr., in a cozy apartment on the third floor of a multifamily house.

Ernest Sr. was a fighter in the Golden Gloves — an especially dangerous amateur boxing circuit with heavy mob ties — in 1948 and 1949 while working as a construction worker. Ann mostly stayed home to take care of Ernie. She was frequently sick. Because the couple had no insurance, they usually couldn’t afford doctor visits, and even when she did get checked, the causes of her conditions often remained mysterious.

Less than two weeks before Christmas, 1956, Ann had fallen ill again. After watching television for a few hours, Ernest Sr. and Ann retired to their bedroom around 10 o’clock that night. Ernie, who was eight years old at the time, was asleep in the other room.

“I need to go to the doctor,” Ann said.

“The only extra money I have is for Ernie’s Christmas gifts,” Ernest Sr. said.

The argument escalated and the last thing Ernest Sr. said was, “You’re nothing but a doctor’s bill to me.” In a nightmare she had that night, Ann dreamed that her husband was attempting to kill her with a gun. Stirred awake by the dream in the middle of the night, Ann looked under the bed and found the suitcase where her husband kept his .38 caliber revolver — the same one from her dream — in case of emergencies. Ann pried the case open. She took the gun out and turned the radio on quietly before drifting back to sleep for about an hour. Waking up again at 5 o’clock in the morning, she stared at her husband for a few moments.

“Ernest, are you tired of me?” she asked him.

When he didn’t respond, Ann cocked the gun before shooting him twice in the chest. Ernest Sr. died instantly. The noise woke up one of the other residents of the house, and Ann ran downstairs saying that her husband had shot himself after they got into an argument.

Detectives took Ann to the police station. After three hours, she confessed to the murder. In her statement to the police, Ann said she worried that her husband had plans to kill her, recounting the dream she had right before she shot him and his comment that she was a doctor’s bill to him. On May 29, 1957, five months after the murder, Ann was sentenced to a term of 18 to 22 years at the Clinton Reformatory for Women (now known as the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women) in Clinton, New Jersey.

Shortly after, Ernie arrived at the Felix Fuld housing development on 125 Rose Street to live with his maternal grandparents in their first floor, four-bedroom apartment. Young Ernie continued to experience confusing changes. First, his grandfather passed away. Then, in April 1961, his mother Ann escaped from the minimum security institution. She was still at large when the events at Mabelle’s apartment in Newark began a month later.

In those startling days after Ernie’s thirteenth birthday, he and Mabelle tallied close to 20 incidents involving plates, mugs, light bulbs, mirrors, and other objects falling or flying around the apartment. At one point, Ernie sat doing his schoolwork at the dining room table when he thought he saw movement from the side of the stove. After he caught the motion again out of the corner of his eye, he watched, as he later reported, one of the pepper shakers from the top of the stove start to levitate above the surface before rapidly floating over and landing beside him. Soon afterwards, according to family accounts, a glass floated from the kitchen sink and crashed onto the living room floor.

With each terrifying occurrence, the two residents grew more perplexed and afraid. Twice during that time, Ernie and Mabelle left to stay with her daughter and son-in-law, Ruth and William Hargwood, at their house in Belleville, the next town over, but they could only accommodate them for short stretches.

Mabelle cherished Ernie, calling him an “unbelievably good boy,” but he presented a frustrating case study in non-communication; the boy who had been through so much upheaval would never acknowledge feeling sadness or fear or, for that matter, anything at all. He mostly replied to his grandmother’s questions with a bland “I don’t know” or “yes.” He seemed to harbor secrets. “I don’t know what goes on inside of him, I just can’t explain it,” Mabelle later lamented. She wanted him to be more open to love. The specter of Ann and Ernest Sr.’s tragedy lurked everywhere, even as Ann herself lurked — nobody knew where — after her escape from prison.

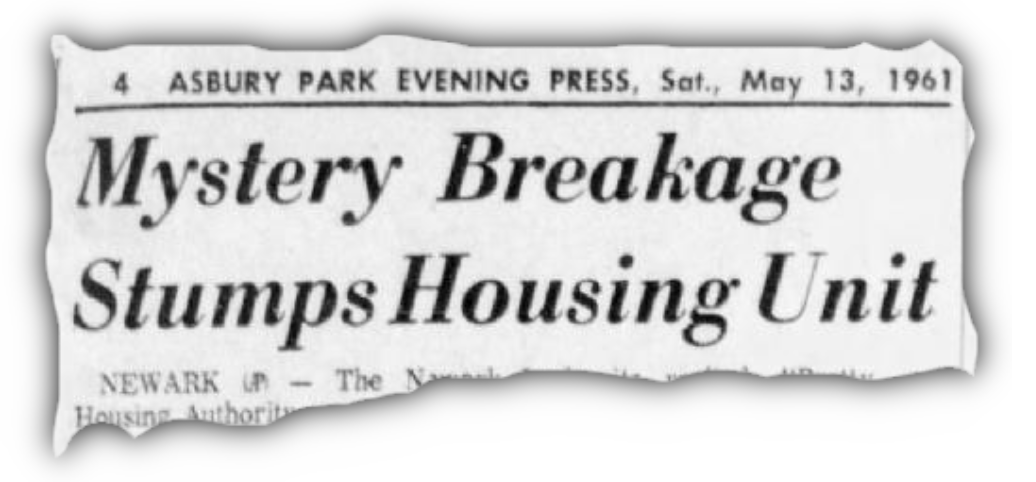

It wasn’t long before other residents and the public started to hear about what was happening at Mabelle’s apartment. Neighbors reported unusual noises. It was only a matter of time before the press picked up on it.

On May 11, Mabelle’s son-in-law William and another relative were visiting when a Newark News reporter, Douglas Eldridge, stopped by. As the five of them chatted in the kitchen, they heard a cup fall and loudly crash by the pantry. Just a half hour before, Eldridge had seen the cup sitting on a sturdy bookshelf. The reporter turned pale — it was impossible for the cup to have fallen on its own without some sort of push. At the time, Ernie had been lying in his bed while the adults sat in the kitchen. “I was laughing when I first came here,” William admitted, not laughing anymore. A distraught Mabelle revealed that it was the fifth incident of the day. Reluctantly opening up to the reporter, she recounted how a small mirror, a bottle of antiseptic, and a light bulb had all crashed and fallen at different times throughout the day. Ernie also described watching another light bulb unscrew itself before crashing to the floor.

Reporters dubbed the events at the housing complex the “Project Poltergeist.” Citing paranormalists’ belief that poltergeists usually fed on the psychic energy of adolescents, journalists eagerly connected the events to the presence of Ernie. For skeptics who suspected a hoax, the 13-year-old boy also seemed the likely source of mischief. Everyone seemed to agree Ernie had something to do with the mysterious occurrences, though he insisted he didn’t have a clue what caused them.

When learning that earlier-documented poltergeists tended to stop after a few months, Mabelle balked, as did a visiting relative. “A couple months!” the relative said, turning to Mabelle. “Why, you’d be in Greystone [psychiatric hospital] by then!”

The housing development opened an investigation. Irving Laskowitz, the Tenant Relations Division director of the Newark Housing Authority (NHA), took charge of the inquiry. In the eyes of many African American residents, Newark authorities often looked for excuses to kick tenants out of public housing, at which point they would be at the mercy of predatory landlords who charged as much as triple the market value for rents.

“I don’t want to move unless I have to,” Mabelle insistently told Irving. “I don’t think this is going to go on forever.”

“It can’t go on forever,” replied Irving, who was dismissive of any idea of a poltergeist under his watch. “Pretty soon, you’ll run out of things to break.”

“Admittedly perplexed officials swarmed through the four room apartment,” the Newark News reported of the investigation by Irving and his team. The officials examined every inch of the apartment as well as the surrounding units and basement. “There must be some kind of magnetism in the apartment,” Irving said sarcastically. One of Irving’s aides added, “Maybe it’s the moon. We’d better check on that.” Despite their snide commentary, Irving admitted Mabelle had a clear record the previous 20 years. And they also found no evidence of trickery or any physical cause for the seemingly invisible force. After things only got worse, Irving later sighed: “I only wish we had.”

The NHA had to acknowledge that a strange, unexplainable phenomena hung over the apartment. They accepted the services of Edward Del Russo, a balding contractor and self-proclaimed exorcist, referred to by one of the housing officials as an “amatuer house de-haunter.” Del Russo said he had “the ability to work with unseen powers.”

“We all have it,” he added, “but few people use it.” He came by the apartment to banish the invisible forces, which he identified as a “lost soul” trying to get a message across to Mabelle. He burned a beeswax candle on their living room coffee table and declared the poltergeist banished. But the forces proved to be immune to his attempt, or maybe became agitated because of them. In the days after Del Russo’s demonstration, the press reported that the disturbances “returned with a vengeance.”

A deep fear took hold of Mabelle — and spread throughout the housing complex — that the spirit of Ernest Rivers, Sr. might be responsible for the disturbances, trying to get Ernie away from her. Ernie, who had already been a target of bullying in the eighth grade at West Kinney Junior High School, had always tried to be strong about it, but now he seemed even more likely to be ostracized. Luckily, the other kids at the Felix Fuld complex stuck by him, especially one boy with whom Ernie was best friends. They continued to play in the courtyard and to go to the movies.

But these attempts at normalcy were a facade. They needed help fast, and needed more than a part-time exorcist.

The media spread the word beyond Newark, until it eventually reached Dr. Charles D. Wrege, a Newark native and respected assistant professor in the Department of Management at Rutgers University with a longstanding interest in parapsychology. After hearing about the curious case, he jumped at the chance to potentially interact with an actual poltergeist, German for “noisy spirits.” Researchers and professionals in the field had begun to refer formally to such phenomena as Recurrent Spontaneous Psychokinesis, or RSPK.

Reports of objects moving, seemingly at random, had been claimed for centuries, and linked to larger supernatural occurrences. In one case from 1846, witnesses and scientists observed a girl who, as she entered a room, would cause objects to scatter “as though physically shoved.” As paranormal researchers began to define the category of RSPK by studying historical and contemporary cases, they theorized that unseen forces interacted on a human “agent,” often an adolescent, which manifested in a physical environment through disordered movements of commonplace objects at hand.

Dr. Wrege, 37, who had a diminutive stature and warm demeanor, planned to come to the apartment to observe Ernie the night of May 12. Earlier that day, Mabelle was in the apartment with Yetta when an iron that weighed five pounds flew into her room. Ernie had been in the bathroom in a different part of the apartment. That night Dr. Wrege arrived and questioned them. Yetta told Wrege she saw the iron “in the air and noticed that the cord was stretched out stiff behind it.” Yetta would also describe to the professor witnessing the cover of a sugar bowl lift up and fall to the floor.

“The stuff came on like gangbusters,” Mabelle added to these accounts. A salt cellar (a large container of salt) launched from a shelf like a missile into Ernie’s back. Yetta also recalled how she, Mabelle and Ernie entered the apartment and, while turning on the lights, saw a bookcase topple over — a bookcase, according to Mabelle and Ernie, that had already fallen over a couple of other times. In another startling moment, the TV overturned as Ernie was turning the key to enter the apartment. Mabelle then began turning the TV to face the wall, hoping that would prevent it from breaking if it were to fall again.

Wrege, who had trained as an engineer, studied the apartment over the course of two days. Just before midnight on the second day, a loud knocking at the door startled Dr. Wrege and Ernie. “We want to see the boy with the flying objects!” a voice yelled from the other side. Several more people were heard in the background — some echoing the first voice in a taunting way while others laughed.

Dr. Wrege and Ernie waited in silence, hoping the group of drunk young men would grow tired and leave. Then a rock sailed through an open window in the apartment. Wrege pulled Ernie into the kitchen to protect him. Just as Wrege was about to pick up the phone to call the police, a glass from the top of the counter fell to the floor. Wrege looked at Ernie — who was visibly upset from the commotion and loud noises outside — standing near the counter. Wrege put his arm around Ernie to comfort him. While Wrege was on the phone with the police, a crash came from the living room. A lamp had fallen off the table and toppled onto the floor, about 15 feet away from them.

“Can you call my uncle and ask him to come get me?” Ernie pleaded softly. The boy, who had tried to remain so stoic, now appeared terrified.

Dr. Wrege, who had still been holding Ernie at this point, let go. Suspicious by vocation, he examined the area for any sign of trickery. “I checked the remains of the lamp and the cord to see if any strings or wires were attached,” he recalled later. But he found nothing. With Ernie having been by Wrege’s side throughout the night, the investigator ruled out any possibility that Ernie was playing a prank.

By the time the police arrived, the group of belligerent men were long gone. Though the white Rutgers professor may not have realized it, even calling the Newark police could be a hazardous choice for African Americans at a time when the city was a tinderbox of racial tensions. Interactions with police could range from antagonism to violence. This time, the cops leaned toward indifference, leaving the housing complex after finding no sign of the disruptive chanters.

Mabelle consults with one of the visiting experts.

Ernie’s Uncle William came by and listened to details from Wrege and Ernie. The three of them were cleaning up the pieces of the broken lamp when an ashtray leapt from the end table next to them, grazed Willliam’s chin, and flew into Mabelle’s bedroom, landing on the floor. Wrege immediately looked over at Ernie, who was holding a dustpan with both hands, collecting the leftover lamp parts. William cried out from the living room. This time, a pepper shaker had struck him in the back.

Growing anxious, the three of them prepared to leave the apartment. Ernie stepped out first and as William was turning off the kitchen and living room lights, William yelled out yet again. A salt shaker had struck him on the back of the head — seeming to slow down as it did — before accelerating and smashing against the living room wall and landing on the ground. As the two men rushed to get out of there as fast as they could, another ashtray on a bookshelf near the door came off the shelf and landed between William and Dr. Wrege. Ruling out rigged objects, Wrege’s records elevated the events to the level of a confirmed case of RSPK.

A few days later, a reporter from the Newark Star-Ledger and the assistant director of the NHA came by the apartment to investigate again. While there, the two men heard a noise in the hallway and watched as a pill bottle on a shelf flew and landed in Mabelle’s room. The reporter, sensitive to suspicions that Ernie had to be behind the incidents, documented that with Ernie in his room at the time he would have had to “teleport” back and forth to have been responsible for the act. When the reporter interviewed neighbors and witnesses, nobody could explain what was happening in the Clark apartment.

Wrege firmly believed the energy of the adolescent was the lynchpin of the case, in the tradition of scholarly literature on RSPK. Wrege decided on an experiment. He asked Ernie to “choose a target for the RSPK forces,” as he recorded in the case files. Ernie chose a mustard jar that he put down on the kitchen table. Twenty minutes later, while Ernie was in the living room and Wrege and William were in the kitchen, the mustard jar “left the table and moved over the heads of the two men,” crashing against the wall. Wrege noticed yet another oddity that defied physics: “the jar,” he reported, “seemed to shatter before reaching the wall.”

In early September 1961, the massive Henry Hudson Hotel in Manhattan’s bustling Columbus Circle played host for three days to a unique group of visitors from around the world: the Parapsychological Association Convention, a blur of dark suits and floral dresses. Between participating in symposiums and lectures, Dr. William G. Roll, who was the director of the Psychical Research Foundation at Duke University and considered a leader in their community, met Charles Wrege. Roll had been reading about the purported poltergeist in Newark when it first became public in May, and after crossing paths with Dr. Wrege, the case now captured his interest.

The German-born Roll, 35, had fought for the Dutch Resistance in WWII before pursuing paranormal studies at Oxford, where he penned a thesis on “Theory and Experiment in Psychical Research.” A dapper dresser with an exotic accent and a love for nature, he commanded every room he entered. On September 9, the last day of the convention, Roll ventured into Newark to visit the apartment for himself. When he arrived, he learned that Ernie had been staying for a few weeks at his aunt and uncle’s place, where no disturbances had been reported. Whatever was happening, a nexus seemed to exist involving the apartment at 125 Rose Street, Ernie, and Mabelle. Roll asked Mabelle to bring Ernie back to the apartment so the professor could observe him there.

Roll, a pioneering researcher and prolific writer on paranormal subjects, had been the one to coin the term RSPK a few years earlier, when the Herrmann family in Long Island reported unexplained phenomena in their home. The Hermanns had two adolescent children, and Roll believed that inner turmoil in the young family members had unleashed the poltergeist — a situation eerily similar to what was now being experienced by Ernie and his family.

Once Ernie returned to stay at Mabelle’s apartment, Roll visited them multiple times. At one point, Roll was in the hall outside the apartment when he heard a commotion. According to Ernie, an ashtray hit the power button on a remote control, shutting the TV off while the boy was in the middle of watching something. As per his notes, Roll rushed into the apartment to witness an ashtray “still moving on the floor.” Ernie was seated quietly and calmly on a couch on the opposite end of the room. Another time when Roll was inside the apartment, money went missing from Mabelle’s purse, with the visiting professor and Mabelle herself suspecting Ernie must have swiped it, however uncharacteristic of him; but his pockets were empty. When the boy took the trash to the basement, he found money strewn around the halls, including one bill ripped in half, all told adding up to two dollars more than what had gone missing, as if the forces were toying with them — this time trying to direct the adults’ ire and blame against Ernie.

Emotions ran high. Just as Roll felt he was coming closer to figuring out what was causing the disruptions, Mabelle grew agitated with the whole investigation. She told Roll and Ernie both to leave the apartment. Roll reassured Mabelle nobody would get hurt. But as Roll began to debate with Mabelle, something hard hit him in the back of the head. It was a bottle. Roll had been facing the direction of Ernie, who remained calm and composed in the same position on the sofa. Ernie later revealed that a bottle struck him, too, when he had walked out of the apartment.

Sending Ernie back to his aunt and uncle was no simple matter of convenience, but also of safety. Accounts of extended poltergeists from the same era described conditions that got so bad they became deadly. In the 1960s, a young girl in Brazil began to be tormented by strange movements of stones and bricks in and around rooms she entered. The incidents turned into an all-out assault when, according to reports, her food was tainted when poison fell into it, and she was suffocated by a series of objects that landed on her face while she slept.

When Ernie’s aunt and uncle no longer had the resources for him to stay with them, he moved back into Mabelle’s apartment. In the coming months, the two reported being terrorized by the poltergeist. The TV set, the washing machine, the refrigerator and even a kitchen cupboard crashed to the floor. Ernie lived in a constant state of terror.

Most of these larger objects were the property of the Newark Housing Authority. In his notes, Dr. Roll recorded the very practical impact: “From being a family problem, the poltergeist now mushroomed into a problem for the housing project and thereby the county authorities.”

The Herrmann family of Long Island, whom Roll had studied in 1958 until their own experiences with poltergeists faded, reached out to express their support to Mabelle and Ernie. “Keep up your courage,” Lucille Herrmann urged, “and don’t panic.” The Herrmanns had been on the cover of Life magazine, and, years later, their case was said to have inspired the classic horror film Poltergeist. While receiving their share of press, Ernie and Mabelle had turned into subjects of rumor and innuendo. Looking back, it becomes difficult not to sense racial bias in the way the compassion for the Herrmanns, who were white and middle class, contrasted with suspicion and distrust of Ernie and his family. The tenants at 125 Rose Street, some of whom had witnessed incidents, generally believed the family’s accounts but also feared a malevolent spirit.

With nowhere left for Ernie to stay, Mabelle brought him to the Newark police station and begged them to take him in to protect him. They refused. They said there was nothing they could do for him unless he broke the law or was deemed mentally unstable. Mabelle brought Ernie to the house of one friend and then another. At each house, a disturbance reportedly occurred and nobody would allow Ernie to stay. The forces — whatever their cause, whatever they were — had broken free of the confines of the housing project and crescendoed.

For the NHA, policy dictated removing problems, or at least shuffling them elsewhere. Irving, the division director, worked closely with a case work supervisor from the Essex County district office and a representative from the New Jersey Board of Child Welfare. A decision was made. Ernie would be removed from Mabelle’s custody and placed in a group home.

Dr. Roll saw a unique chance to more deeply explore a once-in-a-lifetime case. But he was operating under a ticking clock — RSPK cases tended to end abruptly, which investigators believed made them so elusive to observe. Consulting with Charles Wrege and experts at NYU who did an examination of Ernie, Roll scrambled to arrange a trip that December for Ernie to come to the Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University. Since the events seemed to begin and intensify when Mabelle was around, they wanted to make sure she was present, too. Ernie and his grandmother had not seen each other for a month when they were reunited to go to North Carolina. If Roll felt pressure to make a discovery, so did Ernie. This could be his last chance to have an authority figure advocate returning him to his grandmother.

The West Duke Building

The Parapsychology Laboratory, which had been established in 1935, occupied the second floor of what was known as the West Duke Building, a grand Neoclassical structure of white pressed brick. The winter afternoon they arrived in Durham, Ernie and Mabelle were walking down a hallway outside of Roll’s office when a book that was on Roll’s desk fell to the hallway floor. “The poltergeist was still active,” Roll concluded, “and was ready to be confronted on laboratory territory.”

Roll brought them to the Jack Tar Hotel, where a room waited for them. Once Roll returned home, he received messages from Mabelle that things had devolved at the hotel. When Roll rushed back to their room, he arrived to the sight of Ernie on the floor with his arms around the television. Ernie and Mabelle reported that an ashtray had fallen and that a glass smashed while Ernie was inside the bathroom. Ernie described seeing the toothpaste float from the shelf into the bathtub. Then Mabelle related how a lamp that she put on the floor to avoid from breaking flipped over and the phone fell down. That was the moment when Ernie had grabbed the television to keep it from falling over. Roll rushed Ernie to his own house to stay there instead of the hotel. Dr. Gaither Pratt, another psychologist who worked at Duke, ended up sneaking into the hotel to repair the damage.

Laboratory observations began on the Duke campus on December 18, with a bevvy of investigators involved. Stakes and tension mounted as details of what happened at the hotel and at Roll’s office were collected. “The fact that even the Parapsychology Laboratory failed to inhibit the poltergeist,” Roll later reflected, “offered an opportunity for closer observation than we had been able to achieve so far.”

Technicians placed cold metal discs on Ernie’s head as a neurology professor tested his brainwaves. At first, the neurologist concluded Ernie’s tests fell into the normal range, but after reviewing the results he noticed odd spikes of activity he was uncertain how to classify. Dr. John Altrocchi, professor of medical psychology, herded in a group of graduate students to interview and observe Ernie.

Altrocchi became fascinated by the boy. “He is the only person I have ever examined,” Altrocchi reported, “with no discrepancy between self and ideal self” — that is, Ernie did not have an idealized version of himself that he wished to present, further supporting conclusions shared across the board by the investigators that Ernie was not trying to deceive anyone about his role or understanding of the phenomena.

Altrocchi considered how difficult it must have been for Ernie to be an African American boy “being examined by strange white people in hospitals and laboratories five hundred miles from home” (the psychiatry professor’s notes also acknowledged, “I have not examined many negro boys his age”). Duke was still an all-white student body and faculty, a year away from becoming the last major university to integrate its campus. Altrocchi observed that the bashful Ernie tended to keep all his emotions, positive or negative, bottled up, to the point where they seemed ready to burst at any moment. The questioners pushed Ernie to the point that tears filled his eyes, even as he continued to deny feelings. In a word association test, Ernie responded in particular to the words “birthday” and “home,” evoking the first report of the poltergeist on the evening of his birthday at Mabelle’s apartment, which was another in a long line of places he called home that had a pattern of being ripped away from him. The experts observed that just as Mabelle wished Ernie was more open to affection, Ernie longed for a level of attention and love he was not given — or could not be given, considering all the losses of the last few years (a father lost to murder, a mother lost to prison, a grandfather lost to death).

Ernie’s strong exterior broke. He admitted that the kids picking on him at school made him angry. The taciturn boy wouldn’t have recounted the specifics, but the cruel taunting was easy enough to imagine: Look at that police car, Ernie, are they chasing your mom? However much he tried to suppress it, a storm of sadness and fury brewed inside him.

Even darker secrets spilled out. Ernie described the angriest he had ever been in his life as coming in the wake of his father beating him as a child. Altrocchi’s case notes present a fascinating snapshot of inner turmoil: It became clear at an early age, no matter how furious he was, he felt completely helpless and unable to express or act upon the anger. It is as if this way of dealing with — or not dealing with — anger has persevered and generalized so that it pervades his personality now.

What also became clear was that Ernie had quietly lived through a childhood of explosive violence. Altrocchi and his team delved further into the impact of the tragedy of Ernie’s parents on his inner life. It is interesting to note, the case records point out, that his grandmother describes him as timid, like his mother, so that it is conceivable that he has the idea that if he should ever let any anger out he would kill somebody as his mother did.

With such a breakthrough in the psychological workup, it fell on the paranormal experts to accelerate their own examination. A suite was prepared with a one-way mirror to an observation chamber. Dr. Gaither — who had been the one to clean the visitors’ hotel room — volunteered to observe from the other side while Ernie and Mabelle were placed in the meeting room and asked to wait. After a while, Mabelle left for a short period. Dr. Gaither watched as Ernie took two measuring tapes from the table and quickly hid them under his shirt. When Mabelle returned and left again, Ernie threw the two tapes after her. Not seeing Ernie throw the tapes, Mabelle called for Roll and told him another unexplained event had occurred. When confronted, Ernie denied throwing the tapes at his grandmother.

In that moment, everything turned upside-down. For the skeptics who had been circling the case, it would have seemed all that was left was to stamp the whole thing a fraud and declare that Ernie, indeed, had been fooling everyone all along. For believers, they’d have to struggle to reconcile this moment with those others that Ernie could not possibly have manipulated. The biggest twist was yet to come.

The Duke scientists swarming around Ernie came from across the university and other institutions, with experts chiming in from departments ranging from electrical engineering to mathematics. They initiated a polygraph and numerous other intensive tests including the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, the Rorschach test, the Thematic Apperception Test, and figure drawing exercises. From these tests, Roll and his colleagues referred to Ernie as a “daydreamer” with “below average intelligence,” but also showed he had a latent ability to excel.

The polygraph test was conducted by Roll with the professor’s full knowledge that Ernie threw those tapes at his grandma. First he asked Ernie simple questions with simple answers. Did you take a plane to Durham? Did you go to public school when you were living in Newark? Ernie, struggling to keep up with so many tests, slumped down in his seat.

“I’m sleepy,” he said.

“Just sit straight forward, lift your head, and relax,” Roll said.

This led into direct questions about specific incidents, including the one from May when the lamp fell in the living room while Dr. Wrege had his arm around him. Ernie said that he didn’t know how it happened — and the polygraph confirmed his position with flying colors, supporting Wrege’s insistence that Ernie could not have been manipulating the disturbances.

But how to reconcile the incidents independent witnesses — relatives, reporters, neighbors, the housing authority, and paranormal investigators — had concluded had been genuinely unexplained, with the fact the boy threw those measuring tapes in front of their eyes? When questioned, Ernie insisted he did not throw the tapes at his grandmother. Then came a shocker: the polygraph showed Ernie was entirely honest when he denied throwing the tapes. Either Ernie, whom they had just tested in a below average range, had outwitted the polygraph and a cadre of Duke University faculty, or something bigger — something stranger — was going on.

Duke’s Dr. Ben Feather, meanwhile, hypnotized Ernie and confirmed that Ernie possessed no knowledge of throwing the measuring tapes. Feather concluded that Ernie threw the tapes in a state of disassociation, which the team believed might relate to the unexplained cerebral spikes shown in the EEG. Building on this theory of disassociation, what surprised Roll was that Ernie seemed to be unconscious both during moments of the documented genuine events and the instance with the tape measures.

During his interviews with the boy, Feather was able to unearth more of the boy’s past, giving insight into his psyche and — possibly — forces of energy around him. When asked about his father, the young boy appeared to show disdain and described a cruel man who beat him and his mother, which often times landed the elder Ernest in jail. According to these accounts, two years of constant fighting had contributed to his mother killing his father. In Feather’s observations, Ernie did not appear to show any sort of emotion toward his father’s death except relief that his father had not been the one to kill his mother. In another interview, Ernie admitted admiration and fondness for his father.

The team examining Ernie came to the conclusion that the poltergeist experiences were connected to family turmoil as well as psychological distress and trauma. In light of the tests indicating disassociation, these forces invading Ernie’s broken family could now have turned into something even more dangerous and chilling — taking control of Ernie himself to carry on disturbances. Unseen forces controlling objects around him appeared to evolve into unseen forces controlling him. The one-way mirror in the room where Ernie had been at that pivotal moment presented another intriguing element. Supernaturalists believe mirrors reflecting mirrors — an effect sometimes recreated in carnival funhouses — could open paranormal pathways. For centuries, experts of the paranormal have advised covering mirrors while sleeping.

It was the nightmare scenario for the specialists and family members alike: Ernie could be slipping away from them.

Back in Newark earlier that year, Charles Wrege had suggested that Ernie might learn to harness and control the psychokinetic forces that seemed to surround him. Now as the case at Duke came to a head, a pivotal moment had arrived for the experts to either help or discard Ernie. In the case of the Herrmann family, the Long Island poltergeist case, even the police had become involved alongside Roll’s team in trying to understand and overcome the mysterious occurrences — with the Herrmanns reportedly finding peace once the forces were banished (paving the way to what became, quite literally, a Hollywood ending when their journey was immortalized in Poltergeist). Giving hope to Ernie was the fact that Roll had actually moved into family homes experiencing poltergeists, and even ended up becoming a de facto foster father to a young woman who was kicked out by her family after a poltergeist.

But those other cases seemed to be divided from Ernie’s by racial and socioeconomic fault lines. Not only did the police refuse to help Mabelle and Ernie, they turned them away. In the Herrmann case, the investigators could take their time in the single family home both to thoroughly observe the family and help put the poltergeist behind them. But in Newark a continuation of the disturbances would mean certain eviction for Mabelle with a threat to sink into poverty.

Ernie indicated to the team at Duke that “he would really like to live with his grandmother and if only these objects would stop flying through the air he would be able to return to her.” As the moment of truth came toward the end of the family’s stay in Durham, the team could have braced for a possible extended battle grappling with unexplained forces on one side, and with bureaucratic officials on the other, to keep Ernie’s family together and finally give them hope for the future. To finally turn Ernie’s home into a home he could count on.

Instead, they crushed those hopes with a far blunter recommendation to solve the psychological and paranormal crisis.

Ernie and Mabelle should be separated for good.

With the frenzy around the “Project Poltergeist” quieting down, reporters and professors began to leave Ernie and his family alone. After a stint in a foster home and a farm for foster children, Ernie’s Aunt Ruth and Uncle William took him back to their Belleville home. While similar incidents of glasses and items flying and breaking occured in Belleville, far away from the limelight, they proved less violent than in Newark. In October 1965, Ann (whose escape from prison had been short-lived) was paroled after serving eight years in the Clinton Reformatory for Women. Shortly after she was released, Ann was murdered by a pair of alleged mobsters seeking vengeance for the murder of their prized boxer just a few years before.

Unrest in Newark’s public housing, with its drastic inequities and institutionalized racism, as well as police treatment of minority citizens, contributed to a major riot in 1967. A National Guard tank was driven into the courtyard of the Felix Fuld housing project, and the buildings where Ernie had spent so much time echoed with gunfire.

The overextended William and Ruth considered sending their orphaned nephew back to a group home, but they ultimately embraced stability for Ernie. William promised Ernie that whatever was going on with him or following him around, they would face it without the help of psychologists and parapsychologists. The incidents gradually stopped by the time Ernie turned 18 and joined the Marine Corps.

For years after parting ways with Ernie, Roll continued to speak about the Newark events at parapsychological conventions and write about it in technical journals. The 1962 Parapsychological Association Convention, the first to take place after Ernie’s experiences, was hosted for at the Jack Tar Hotel, where Ernie and Mabelle had stayed, and featured talks on what had happened in the Newark housing project. The case contributed to Roll’s rising stock in the paranormal community.

Ernie remained in New Jersey through adulthood. He married and had children of his own, the violent incidents receding into family lore. But later, Ernie’s wife claimed to experience some unusual phenomena in the house. An occasional glass would drop in the kitchen from time-to-time. There was one moment in particular she never forgot.

She woke in the middle of the night to glimpse what she believed to be a man sitting on their windowsill. Startled, she jostled Ernie to let him know what happened. Ernie responded as though he knew just what it was she had seen.

“Just go back to sleep,” he said. “Don’t worry about it.”

SALEAH BLANCAFLOR is a New York- and New Jersey-based writer originally hailing from Oklahoma. Her bylines can be found in NBC News, People Magazine, Entertainment Weekly, Real Simple, Texas Monthly, Eater and more.

For all rights inquiries for this and other Truly*Adventurous stories email here.