A single working mom begins a whirlwind romance with a man named Martin Lewis, then discovers that Martin Lewis doesn’t exist. This true story picks up right where Scorsese’s ‘GoodFellas’ left off.

Sherry Anders was in a bind. She’d just told her roommate about an injury to one of her horses. They were seated at a table in El Toreador, a family Mexican restaurant near their shared split-level in Redmond, Washington. Sherry, a petite 5’2” with dark hair and knock-em-dead looks, grew up around horses and could handle them better than most stable boys — and with style to spare. “She’s the only person I ever knew who could go horseback riding in heels and white clothes and come out looking absolutely gorgeous,” recalls a longtime friend. But Sherry hated needles and was dreading giving a shot to Flame, her red quarter horse.

That’s when an affable, 38-year-old guy with dark hair and eyes appeared at their table and flashed a thousand-watt smile. He introduced himself as Martin Lewis and told Sherry he owned and raced Thoroughbreds. He produced a wallet-size photo of a beautiful filly draped in a celebratory garland of flowers. At the center of the photo, Martin and some associates grinned ear to ear, glowing from a recent victory. He’d be more than happy to administer the shot, he told her, flashing the smile again. Sherry couldn’t help smiling back.

The chance encounter led to a date, and thereafter the two were inseparable. Sherry, a beautician and rising star in the world of hair and makeup, had been around a lot of big personalities, but Martin took the cake. With his thick New York accent and impeccable fashion sense, he stuck out like a sore thumb in Redmond, which was still a sleepy city in the early 1980s, a few years before Microsoft moved its campus there.

Sherry’s friends worried she was falling too hard too fast. Raised Mormon in a small town in rural Washington, the single mom was trusting to the point of naive — at 31, still green to the ways of the world. But even the most guarded in her circle had to admit there was something appealing about Martin. He wasn’t attractive in a conventional sense, but what he lacked in good looks he more than made up for in raw magnetism. And he and Sherry were clearly infatuated with one another. “It was magic,” recalls Sherry. “Electric,” is the word chosen by Samantha Kellum, the roommate who was with her that fateful night at the restaurant. “The electricity during those months was just absolutely volatile, just screaming.”

Seven weeks after the fateful meeting in El Toreador, Martin surprised Sherry with a pronouncement: “Let’s get married today.”

Sherry was stunned.

“What do you mean? I can’t get married today, I have work.”

But Martin flashed the smile, which always betrayed a little bit of the devil in him, and Sherry melted. They raced home and packed overnight bags, then piled into Sherry’s new Honda Prelude with Kris, her 13-year-old son from a previous marriage. The impulsiveness of the decision matched everything about their whirlwind relationship, and Sherry floated down the highway toward Virginia City, Nevada, as if on a cloud. At long last, she had found true love.

Only there wasn’t much that was true about Martin Lewis. He didn’t just have a double life, he stacked up secret lives like Russian nesting dolls. He was already married and had a house across town where he lived with his wife and two teenage children. And that was just the icing. His real name was Henry Hill, and everyone close to him wore targets on their backs.

A quick primer on the mafia career of Henry Hill for those who have managed to avoid multiple viewings of Martin Scorsese’s 1990 film Goodfellas, which dramatized his criminal history and became one of Hollywood’s most memorized movies. As a starry-eyed kid in Brooklyn, Henry ran errands for Paul Vario and Jimmy Burke, shot-callers in rackets and smuggling for the Lucchese family branch of the mob. Henry’s responsibilities expanded until he played a conspicuous part as an “earner” for the mob crew, with a key role in the multimillion dollar heist of Lufthansa Airlines in 1978. When the attention brought by that robbery turned up the heat on everyone connected, and with Henry’s involvement in a rogue heroin ring triggering pressure from the law as well as from his bosses, Henry turned informant to save his life and the lives of his family.

With his Goodfellas era over, a man who had never known life outside the mob was unleashed on an unsuspecting world as one of us. In May 1980, when he sat down in the office of Ed McDonald, the prosecutor who was arranging his entrance into Witness Protection (WITSEC for short), Henry brought along two of his mistresses and tried to enroll them in the program along with his wife and children. It was the first in a string of unbelievable stunts he would pull while in the program.

The Hills hoped to be placed somewhere glamorous and warm, but they got Omaha, Nebraska. The lanky man with the thick Brooklyn accent might as well have been from another planet. For their first meal out, Henry took the family to Omaha-based-chain Godfather’s Pizza, as if to dare the Midwest to change him. It felt like he’d arrived at the ends of the earth, all flat land and sky, cows at pasture everywhere he looked. “It was like another country,” Henry recalled later. He claimed his body could never get off New York time, so he would be up an hour too early every morning, dressed to the nines in expensive suit and shiny loafers, nowhere to go. At the grocery store, he and an employee stared each other down over Henry’s request to be directed to the Italian food. He bought out their supply of Ronzoni lasagna noodles.

Henry Hill

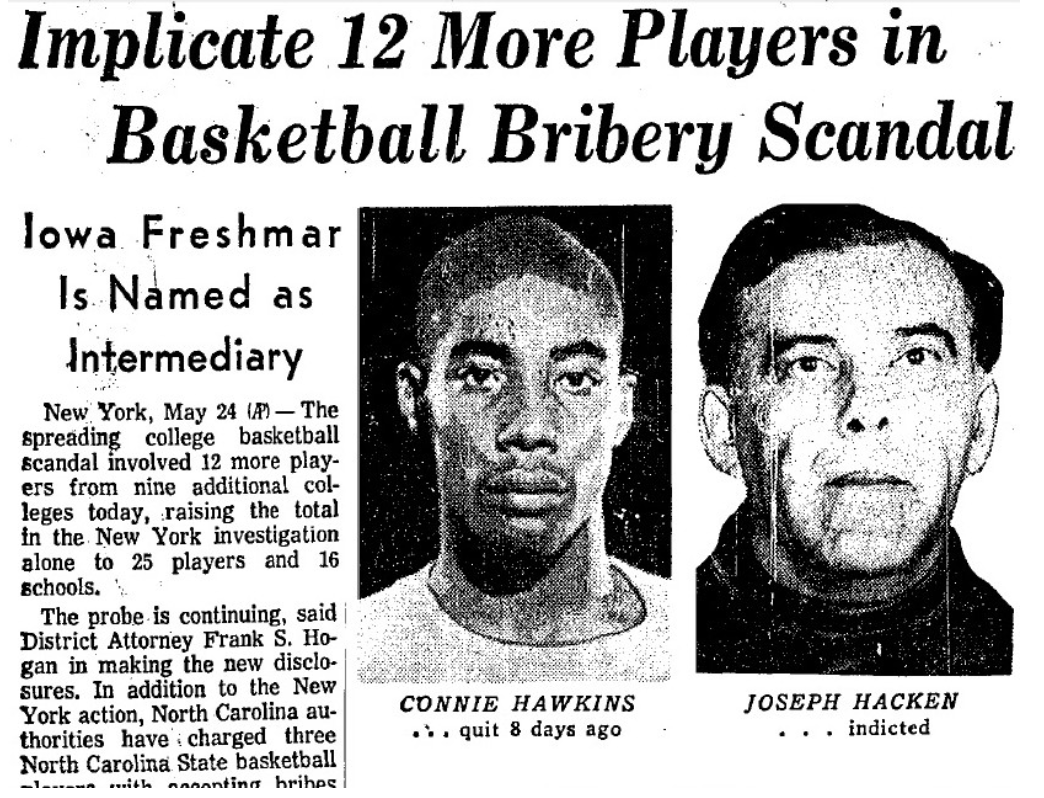

His cover stories ranged from working for the government, which had a kernel of truth, to being an insurance investigator for arson cases, which was a complete fabrication — although he had torched a half dozen places over the years. Periodically he was transported back and forth to New York to testify against Vario and Burke. Skirting the law since elementary school, spilling about all of his criminal activities took time. The splashy Lufthansa heist racked up headlines but proved tricky to prosecute, in no small part because Burke had ordered his goons to kill pretty much everyone who’d been in on it, with Henry next on the list. Even with all the beatings, whackings, and extortion he’d witnessed, Henry’s highest value to the government came in his ability to implicate Burke in fixing college basketball games and to stick Vario with a parole violation, of all things. If given the opportunity, the bosses would relish putting their former protege six feet under.

Court cases grind slowly, and in the long intervals between testifying, Henry was riddled with anxieties. “It’s not easy getting up on the stand,” he later explained of the swirling emotions brought by flipping on his ex-mentors. A therapist thought turning informant had given him a secret death wish. His patterns of excessive drinking and, often, drug use, re-surfaced, heightening the risk of blowing his cover while his wife and kids did everything they could to lay low. Meanwhile, a reported two-million-dollar contract was placed on his head and wiseguys tried to bribe relatives back east in order to track him down. At one point, in a courtroom hallway, Burke was overheard hissing that he knew Henry was in the Midwest. Evidence suggests Henry had also been making collect phone calls from Omaha to New York, which Henry’s son heard was a play to force the government to move them somewhere, anywhere, far from Nebraska.

Mounting concern that the Hills’ cover was fraying led to the marshals swooping in and whisking them away to new identities and a different home in Independence, Kentucky, population a tick under 8,000. In Kentucky, they likely lived in an obscure residential community called Beech Grove. Henry, who’d converted to Judaism for his wife, complained there were no Jews to be found.

Henry Hill was a witness against Jimmy Burke in a now-infamous college basketball points shaving scandal.

A moth to the flame of money making schemes, Henry turned to horses in Kentucky. He became an unwanted fixture at the Latonia (now Turfway) Racetrack, where he placed bets with inside information and may have drugged horses. No wonder later on he could boast, truthfully for once, that he knew his way around the animals. He later claimed he also sidelined as a pimp for one of the female racetrack employees who turned tricks in the stable area.

Henry even began operating a horse drawn trolley tour of nearby Cincinnati. He made sure to ride his passengers by the fountain featured in the opening credits of the popular sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati. The thriving business attracted the attention of the Cincinnati Enquirer — on the front page of the Metro section, Henry can be seen in a photo, with perm and fake mustache, trying to run out of the photographer’s frame.

The marshals in charge of keeping Henry alive had to worry not just about fellow criminals getting to him, but also about law enforcement. “I was the best mob informant [they’d] ever get,” he later said, which sheds light on why he expected the government to bail him out of jams as fast as he could get into them. He boasted he had a “King’s X,” a playground term for being exempt from the rules of a game.

He was arrested for getting into a fight with a woman, likely a mistress, in April 1981, and then again in July for passing bad checks. A local investigation into horse thefts led to Henry. It turned out he’d procured exotic Belgian draft horses for the trolley but neglected to pay. He couldn’t possibly have picked a worse man to stiff: John Y. Brown was former owner of the Boston Celtics, the man who turned Kentucky Fried Chicken into an empire after buying it from Colonel Sanders, and the current governor of Kentucky. McDonald couldn’t believe when he heard. The blunt mantra in WITSEC was “don’t do anything.” Instead, Henry swindled the governor of the state he was hiding in. A sharp detective on this case even discovered he was in Witness Protection.

The exasperated marshals had no way to clean up their star witness’s epic messes in Kentucky. The family would be uprooted for a third time in only a year and a half of living undercover. Multiple moves required invented names. As if to underline how un-seriously he took the danger he put himself and those around him in, Henry’s latest identity combined the names of his favorite comedic actors. Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis became Martin Lewis.

Finding themselves in Redmond, Washington, the Hills bought brand new lumberjack- chic boots and plaids then traded them right in at Goodwill for old lumberjack-chic uniforms, a trick Henry had learned from years of observing unconvincing undercover cops. Defying all basic caution, Henry sent word back to an acquaintance in Kentucky to ship a horse named Banana Split, which he had gotten for his daughter, to their new location in Washington State. With a few more horses added over time, the former New Yorkers held impromptu polo matches in their fields. Henry liked the fact that he saw a rainbow shortly after they arrived. It signified a fresh start.

But soon Henry — Martin now — lost his patience for blending in, and his recklessness and hustling intensified. Over time, he got involved in drug deals, which explained the warning his wife received one day when picking up the phone: “Tell Marty he’s dead.” In the fall of 1981, when Martin walked into El Toreador, one of his favorite new hangouts, he had his eye out for easy money and romance, two things that seemed bundled together in a woman named Sherry Anders.

The night of their quickie wedding, Sherry and Martin stayed at the International Hotel in Virginia City, Nevada, where they fooled around in a bed purportedly used by Ulysses S. Grant during an 1879 stopover. Under the bed’s broad, opulent headboard, Sherry felt like a princess who’d found her prince. Her Mormon grandfather always told her people lied, but numbers didn’t; she was seven years younger than Martin, and her parents were seven years apart, a sign the union was meant to be. Martin called her his Sherry Amour (inspired by Stevie Wonder’s My Cherie Amour) and told her she was the love of his life. Her pet name for him was Morton. From a payphone, they called around with the news. Marty called a good friend named Ed, whom Sherry had never met. “She looks just like Elizabeth Taylor,” he told Ed. “Here, talk to my friend,” he blurted, thrusting the phone to Sherry. Ed congratulated her.

Back in Washington, Sherry’s friends worried things were moving too fast. Vivian Walsh, who owned the salon where Sherry rented a chair, got a bad feeling about Martin the first time he stopped by during work hours. “He kind of slinked in and didn't make good eye contact when I was introduced,” she remembers. “I said, ‘You know, I hope that's not a red flag, but there's something kind of creepy about him.’”

Vivian had reason to be protective. Sherry was trusting to a fault, a hopeless romantic with unfailing optimism. That open-to-the-world buoyancy had led to some rough patches with men in the past. A seven-year marriage to her high school beau ended in a messy divorce, and she was now raising her teenage son Kris on her own. More recently, in the months leading up to Martin’s arrival, she’d dated a handsome Italian-American named Alamo, whom she thought might be the one. Vivian had the same distrust of Alamo she would later have of Martin, and those earlier suspicions turned out to be right on the money when Sherry’s boyfriend convinced her to invest in a business venture that lost everything.

But even Sherry’s most skeptical friends couldn’t deny there was something exciting about Martin. With his designer clothes and tendency to flash money, he was a dollop of New York color in monotone Redmond. When Vivian and her husband began double dating with the newlyweds, Martin took them to the best restaurants, handing hundred-dollar tips to kids who didn’t see that much in a week. He was a showoff, but he was generous to a fault and seemed to have a good heart, just like Sherry.

Martin moved into the Redmond split-level Sherry shared with her lifelong friend, Samantha, who also had a son. The two women had grown up together in a Washington farming town, where the most trouble they got into was taking the family car without permission. Not long after high school they moved to Los Angeles, where they studied hair design and rubbed elbows with celebrities like Harry Belafonte and Joe Namath. Hugh Hefner invited them to the Playboy Mansion, which they declined. Even during disco’s halcyon days in Hollywood, they were good girls at heart and confined their partying to light drinking and endless flirting.

After they made their way back to Washington, Sherry and Samantha focused on establishing themselves in separate corners of the competitive beauty industry and settled into quiet, overlapping lives. The Redmond split-level in highly desirable Education Hill bore telltale signs of the friends’ wholesome upbringing, complete with strict curfews and bed times for the boys. A black pygmy rabbit, a cat, and a ferret named Ferret Fawcett had the run of the place and spent long hours tearing around the living room. The two women sometimes went out dancing, but more often their nights out began and ended at El Toreador, the local Mexican restaurant, where they knew the owner, Wayne Humphreys, and many of the regulars.

Martin plunged into that picture of domestic simplicity like a raging bull. One morning, shortly after moving in, he stumbled into the kitchen with a massive hangover and asked Samantha if she had a valium. “He was rubbing his face and wobbling a little bit. And I kind of jerked back like, ‘Why would I have a Valium?’ We were not drug culture kids.”

But like Vivian, Samantha watched her misgivings disappear under an assault of Martin’s unflappable charm. They all went out together, and for the two friends it felt like rediscovering a part of themselves that had been lying dormant. Sherry wore gorgeous outfits, like the black tie-at-the waist Donna Karan dress, which she adorned with a long black trench coat Martin bought her. Samantha wore crisp white blouses and basket-weave full-length skirts. They were stunning, the center of attention wherever they went, and life felt exciting, just as it had in Los Angeles.

Martin was also wonderful with the two boys, always bringing home quarters for the arcade and making them laugh with off-colored jokes. He bought a foosball table for the basement and invited the boys along with him on errands. Sherry liked to joke he was a five- year-old trapped in a 38-year-old’s body. The hearty Italian food he’d throw together made Sherry worry about gaining weight, but it was wonderful to have someone cooking for them. “He was a great chef,” she remembers, “he had all these expensive pots and pans.” He prepared an array of dishes from manicotti to pheasant in sour cream. It galled Samantha that the happy couple left her to clean up, but she had always been the responsible one in the house. Martin was a fun-loving extension of her dear friend.

To contain his collection of designer clothes, Martin built a special closet in the basement. Among his other possessions was a baroque white rotary phone with gold details. He talked on the phone nonstop, dragging the long cord around the house. He was a writer under contract with Simon & Schuster, he told Sherry, and the publisher was certain his book would be a bestseller. That explained the occasional infusions of cash, which always brought on binges and shopping sprees. The as-yet untitled book was all about his life back in New York, was all he would say, unfurling the smile before changing the subject. To some of his drinking buddies in town, he claimed he worked for the CIA.

If there were any doubts Martin was working on a book, they were put to rest with the arrival of Nick Pileggi, a bona fide journalist from New York, whom Martin introduced as his co- writer. Nick began making frequent trips to Redmond. The two would hole up in the house, drinking and working on the book. When Nick wasn’t around, Martin was either talking to him on the phone or recording long, rambling soliloquies on micro-cassettes, which he later mailed off.

Nick, who was tall and soft spoken with chiseled features, was around so much he and Samantha even struck up a casual romance, and for a brief period the four of them — Sherry and Martin, Samantha and Nick — were inseparable. Out of the blue, Martin announced they were all going on a trip to Canada immediately, and the girls raced to pack bags. They didn’t question why it seemed so important to Martin to leave the country. He was an impetuous guy and they were just happy to be along for the adventure.

In Vancouver, Martin gave Sherry and Samantha a stack of cash to go shopping. Writing a book seemed like a mystical process to them, and they didn’t want to disturb it by asking stupid questions. They had no idea that a mainstay of true crime literature, Wiseguy, and ultimately trailblazing cinema in its future adaptation, Goodfellas, was being born right under their noses. Martin insisted on Asian cuisine when they ate out, and they would order bottles of Dom Perignon, which Martin pronounced “Don Perig-nin”. Sherry loved the pomp but wasn’t a drinker, and she would dump her champagne into the plants. The lovely trip was capped off with dinner at a Japanese restaurant, where they sat on cushions and Martin flirted with a server in a geisha outfit.

Back in Washington, still in the fever dream of the relationship, Sherry began taking more appointments at work. She had always been a hard worker, more than able to make ends meet, but lately her money didn’t seem to stretch as far. Between installments from his publisher, Martin borrowed money from her and racked up big debts. Even the money for the foosball table he bought for Kris, which was such a hit, came out of Sherry’s account. He promised to pay her back, but it strained her finances. When they visited Sherry’s family back in her hometown, he made promises about paying for Kris’s future college education. Sherry’s sister Catalina, one of more than a dozen foster children taken in by Sherry’s parents, Laura and John, had a bad feeling about Martin, but she didn’t say anything. Once Sherry loved someone, Catalina knew, she loved someone.

A few weeks into their marriage, Martin’s behavior became even more erratic than usual. “You’re too good for me,” he told Sherry one night, drunk on her couch. “I feel so guilty at my life.” The meaning flew over her head. Always impatient, he began calling the operator whenever he got a busy signal. “I’m Dr. Lewis. I have an emergency and need to get through to that phone.” It usually worked. One day, Martin showed up to El Toreador in a t-shirt that read “Witness Protection Program.” Everyone in Redmond thought of it as a quirky joke, a play on the fact that nobody could quite figure out where he came from or what he did all day.

There were fights, often followed by make-up sex. The first big blowout as a married couple came after Martin demanded Sherry do all his laundry. She had just come home from a full day at work on her feet and wasn’t about to pick up after him. “I’m not your maid or your mommy!” she shouted. Martin told her he’d thought it over and only wanted to be married three days a week. She hoped it was just another of his hurtful barbs. Then there were the New Year’s plans Martin didn’t show up for, leaving Sherry crying for hours. Sometimes he disappeared for days-long jags. “He was like a ghost,” remembers Sherry’s friend Sande.

Sherry chalked all of this up to growing pangs, the stresses of a new relationship. She loved Martin and was certain he felt the same way. But by turns she became haunted by a feeling that something wasn’t right.

One day, at the salon, an unfamiliar young woman walked in for an appointment. The woman was in her mid-twenties and introduced herself as Janet. Sherry, who plastered her wall back home with photos of Golden Age actresses cut out from magazines, thought her new client looked like a young Katherine Hepburn.

The appointment started out as any other. Sherry complimented Janet’s curly strawberry blond hair and the two chatted about the usual nonsense: weather, celebrity gossip, news. Keeping clients at ease is one of the tools of the trade in the beauty business, but Sherry soon found that Janet was asking more questions than she was. The young woman seemed particularly interested in her recent marriage to Martin. Sherry began to have the uneasy feeling she was being interrogated. Janet gave the impression that she knew Sherry’s husband — or at least knew of him.

She tried to forget the strange encounter as soon as it ended. Back home, she’d be greeted with romantic gestures, a delicious dinner, flowers, slow dances to Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” and Willie Nelson’s “Always on My Mind.” Martin often made her laugh so hard her jaw hurt. They talked about building their dream house, and Martin had taken charge of clearing a property she’d inherited. Everything was exactly as it should be, she told herself.

Not long after, driving through Redmond, Sherry spotted a woman in a beat-up green Ford Pinto, the same car Martin drove. She pulled up next to the car at a stoplight and rolled down the window. The woman behind the wheel was about four years older than her, a bit tired looking but attractive. It didn’t occur to Sherry then, but the woman had the same dark hair with hints of red that she did, and similar facial features.

“Do you know Martin Lewis?” Sherry asked. “Yeah,” the woman replied. “He’s my husband.”

If Janet Christensen had been less dedicated to her craft, she might have warned Sherry Anders that the man she knew as Martin Lewis was already married to another woman. The Katherine Hepburn lookalike felt truly sorry for Sherry, whom she’d been watching for weeks and knew to be kindhearted, if naive — so sorry, in fact, that she almost breached protocol and spilled the whole story during her recent salon appointment. But Janet was a professional. She had a job to do.

The 25-year-old sat in her 120-square-foot downtown Seattle office, which was strewn with potted plants and old case files, pecking out paperwork on the keys of her electric typewriter. In off hours, when not running down leads or chasing deadbeats, she used the same typewriter to work on a novel. The novel’s main character was a no-nonsense private detective named Janet. Janet, the one typing, was also a private detective. A New York law firm had hired her to look into Henry Hill, aka Martin Lewis, based on its understanding that he was in Washington state. The firm represented Henry’s former mob boss, Jimmy Burke, one of the people who wanted him dead.

On the surface, Janet might have seemed an odd choice of investigator. The scion of a prosperous California family, she had no law enforcement training, and she hardly fit into the traditional mold of one of Raymond Chandler’s grizzled, hard-drinking protagonists.

Then again, the Seattle Detective Bureau, which she’d founded in 1979, was enjoying a a run of good press. It was the first female-led private eye agency in Washington state, one of the only female-led detective agencies in the country. One of its earliest cases targeted a Washington sheriff, George Janovich, who was soon sentenced to six years for racketeering, for which Janet claimed some credit. Along with the other two female detectives originally at the agency, they were labeled Charlie’s Angels after the hit TV series, though Janet scoffed at the moniker. “Brains, not beauty, solves cases,” she said in interviews.

Even so, the agency developed a reputation for finding people who didn’t want to be found, and Janet and her ever-changing crew worked cases in ways that would be well-suited to a television spinoff. “I’ve jumped from a burning car,” she told a reporter around the time she visited Sherry in the salon, “I’ve had to scale a high fence, I’ve been wrestled and thrown to the floor ... You can’t afford to be afraid and do your work. If you’re afraid, you should go into other work.” She accepted the risks. “My life will always be dangerous,” she wrote to a friend. She kept a GI Joe doll in her car’s ashtray, a reminder of ideals of morality and justice she wanted to uphold.

Rounding out her staff on the biggest cases — and Henry Hill was as big as they came — was buoyant, mustachioed Charles Preston, whom the Seattle Daily Times profiled as a kind of African-American version of Mike Hammer, Mickey Spillane’s fictional detective. Just as Janet didn’t fit any mold, in the Washington State of the early 1980s, it simply didn’t occur to people that a young black man could be a private investigator, a fact Preston used to his advantage. (At least, usually: “Sometimes when they see a black man sitting in car in their neighborhood, they automatically call the cops.”)

In light of the agency’s recent successes it made sense Burke’s lawyers would call them. They wanted Janet to find Henry Hill and dig up dirt on the government’s star witness, which the defense would make ample use of to discredit his testimony. How they had known to look in the greater Seattle area is less clear. The US Marshals may have miscalculated in carrying over Martin’s alias from Kentucky to Washington, possibly believing the location had been compromised but not the name. Kentucky Governor Brown initiated a lawsuit for the Belgian horses Martin swindled from him, and that legal paperwork may have scattered clues into the public record, although it’s unlikely there would have been any mention of Washington State.

The holy grail, for anyone who had figured out that Henry Hill was now going by the name Martin Lewis, would almost certainly have been Martin’s marriage to Sherry. Though recorded in Nevada, the marriage license listed residences in Washington. Burke’s lawyers — and possibly his goons — had their man. Find Sherry Anders and you’ll find Martin Lewis, they told Janet. So Janet, Preston, and even a teenage boy she sometimes paid to pose as her son, went to work. Using disguises when necessary and relying on their Judo training to keep cool under pressure, they had been staking out Sherry at home, at the salon, and around Redmond’s shopping and restaurant district practically since she and Martin returned from their impromptu honeymoon.

They had Martin firmly in their sights, confident they could get him booted from WITSEC. “I especially wanted the dirt,” Janet later recalled.

It wasn’t easy to shock the woman at the wheel of the Pinto, not after all she’d been through, but coming face-to-face with her husband’s other wife came close. Born Karen Friedman, married as Karen Hill, she had been using the alias Kaylen Martin since U.S. Marshals moved her family from Nebraska after another of her husband’s reckless stunts. She liked the name Kaylen and was glad the Marshals allowed her to keep it in Washington. It had the virtue of sounding like her real name.

Married to a mobster half her life, Kaylen thought of herself as the rock of her beleaguered family, which consisted of her husband, now going by Martin, and two teenagers, her pie-in-the-sky daughter, who was going by Gail, and her somber son, whose alias was Michael. She had also accumulated a menagerie of dogs, cats, a cockatiel, and Banana Split, the horse her husband, against all reason, had asked a friend to ship to them from Kentucky. Kaylen should have been furious with Marty for that flagrant breach of protocol, but Bananas made Gail happy, and Kaylen savored any sign of normalcy in her increasingly distraught kids.

Not that their lives had ever been normal, per se. But at least in New York she could hide much of what was going on from the kids. There were the odd times a family friend would turn up on the news, either in cuffs or found in pieces dumped someplace, or when Martin was in prison — those were tough to hide. But Kaylen had a good sense of humor and was a good listener, and she became skilled at weaving their childhoods around all the madness of her husband’s life.

WITSEC was different. There was no chance of normalcy anymore, though they had to explicitly pretend to be normal. And with a contract on her husband’s head, the generalized anxiety of being married to a criminal had turned to acute panic. Kaylen frequently climbed into the Pinto, which they’d found at a used lot soon after arriving in Redmond, just to get away from the chaos their lives had become. They lived in a rundown ranch-style mansion that Martin and his adoring daughter nicknamed the Ponderosa. The pets, the kids’ angst, the eccentric old man they were taking care of for extra cash, the booklets and pamphlets for her own certifications in a long line of career moves — sometimes she just needed to drive Redmond’s long, peaceful roads and lose herself in the bucolic scenery.

“Do you know Martin Lewis?”

The question, shouted from the car next to hers, acted like a starter gun for her nerves.

Sherry stared at the woman in the Pinto in disbelief, certain there had been some mistake. “He’s my husband,” she retorted. “I just married him.”

“No,” Kaylen answered without joy, “he’s my husband.”

“We need to talk.”

Sherry followed the Pinto to what she would soon learn was the Lewises’ rambling ranch-style home, the Ponderosa. They sat and talked, and Kaylen, too numb to be surprised by her husband’s misdeeds, laid it all out. “I created my own monster,” Kaylen said of enabling Martin.

Sherry, a good Mormon girl from rural Washington, was bowled over. It seemed like a practical joke, but there was also an odd plausibility to Kaylen’s outrageous tale. Sherry was too shocked to unleash her anger, even when Martin showed up a short time later and gawked, wide-eyed, at his two wives. All the way home she tried to process the information that had suddenly capsized her happy life. Martin was really Henry Hill, a mobster turned informant, and he was being protected by the government, which was using him for testimony in various cases. Aside from all that, worse, even, in her view, he was already married with two children.

Meeting Gail and Michael, Sherry was impressed with them, especially given the circumstances. A testament to her kind heart — and the whiplash she was feeling — she even arranged to have one of her horses, Teriyaki or Terry for short, sent over for Gail, who was a horse lover like Sherry.

But back at her own house, Sherry’s composure cracked. She opened the second-floor window and tossed out Martin’s fancy pots, pans, and knives, which had produced so many gourmet meals for her and Kris. Next, she heaved out all the expensive suits made by Armani, Brioni, and other designers not often seen around Redmond. One of the neighbors came over and asked how much the items were at the yard sale. It began to snow — relatively rare for the area — and Martin’s things were soon buried in a fine white powder.

The dramatic gesture felt good, but the marriage, her feelings, could never be buried so easily. When Martin found his suits caked in snow and mud, he cursed like nothing she’d ever heard. She scowled at him, unable to understand how he could be so selfish.

“Don’t you ever fucking come back here!” she screamed.

Then she cried, and it felt like she would never stop.

Shortly after the revelation, Sherry received a phone call. With the cat out of the bag, private eye Janet Christensen felt she no longer had to tiptoe around. She wanted to meet, she said, and after avoiding Janet for a while Sherry finally agreed.

It was disconcerting for Sherry that a stranger knew so much about her life. She listened to the array of details Janet knew about Martin, adding them to what she’d learned from Kaylen. The pieces of an insane puzzle began fitting together. The black sedans that parked across from Sherry and Samantha’s house so often in the last few months? US Marshals assigned to keep an eye on Martin. The hush-hush book project and the impromptu trip with Nick Pileggi to Canada? The book was about all this, his past crimes and the mafia, and the writing retreat over the border removed them from the jurisdiction of the government, which wasn’t keen on Martin spilling information that was vital for convictions in his tell-all book. It even made sense why they had eaten at Asian food places during the trip: Martin had intentionally avoided the great Italian restaurants in Vancouver out of fear of running into any wiseguys.

There were also the drunken comments by Martin, his guilt over his past life. She even recalled the t-shirt that read “Witness Protection Program,” which wasn’t just a random slogan, it seemed, but a perverse, kamikaze commentary on his own secret life. And there was the money. As Sherry began her own investigation into the man she had married, she spoke with a bank teller who said she’d never seen someone withdraw money as frequently as Martin did. The big tips, the exorbitant, out of control spending: He was trying to recreate his high life in New York.

Sherry broke the news to her mother, who had adored Martin, and to Kris. The teenage boy was heartbroken to discover the truth about the new fun-loving father figure in his life, whom he described as “pretty much like a big kid.”

With no job and few stable attachments, Martin was still letting himself in and out of Sherry’s house at odd hours. At one point, Samantha found a message written on the bathroom mirror in lipstick. I love you, Sherry Amour, HH. “Who’s HH?” Sherry now unspooled the tale of Henry Hill to Samantha. Searching the house, they found a mayonnaise jar filled with what seemed to be cocaine.

Redmond was a relatively small town of about 20,000 people. On her way to an aerobics class, one of the few outlets that offered a refuge from the rage and grief she felt, Sherry had the bizarre experience of running into Kaylen. She found it strangely comforting, as if meeting another survivor. “Oh, that dirty sonofabitch,” Kaylen lamented, and then told Sherry about some of his past infidelities. The temporary alliance relieved the pain, and Sherry had that adolescent sandlot thrill of plotting some comeuppance.

“You want to have some fun?” she asked Kaylen.

There was a dance club behind El Toreador. Sherry had heard from one of Martin’s drinking buddies that he was planning on being there. That night, Sherry and Kaylen walked in arm and arm. “Here’s wife Number One and wife Number Two,” Sherry announced. “Isn’t that special?” Martin’s jaw dropped, and as his two wives danced up a storm, he drank himself into a stupor.

A touch of revenge was sweet, but the relief was fleeting. Deep down, she still loved Martin. Worse, she believed he still loved her. In her heart, she believed their time together had truly meant something to him. The alternative would have been too difficult to bear.

As usual, Martin had somehow assumed he’d get away with it. He even bragged about his second marriage. His friend Ed, the one he called from a payphone in Nevada with the news? That was Ed McDonald, the put-upon prosecutor overseeing Martin’s case. McDonald still remembers the call well because it came in at a crucial juncture in the Boston College point shaving case, in which Martin was his star witness against Burke. He was waiting by the phone for a call telling him the jury reached a verdict.

“What are you, an asshole?” he asked Martin on the phone. He had often quipped that Martin had done everything in the criminal alphabet, A to Z. “I guess you didn’t have anything for ‘B’ so you came up with bigamy?”

Martin had boasted to Nick Pileggi, too, attempting to clear things up by explaining that Henry Hill was still married to Kaylen, it was Martin Lewis who married Sherry. Nick hung up on him.

Also as usual, Martin’s family was left picking up the pieces when the insane stunt blew up in his face. This time, the stakes were unbelievably high. Sherry, who in the days after the revelation unwisely turned to the older Kaylen for support, let slip that a private eye had been investigating the Lewises for months and had been in contact with her. Hearing this, Kaylen snapped to attention. Janet’s sleuthing marked a serious risk for her family. Burke, along with Vario, wanted Martin dead both for revenge and to protect themselves from his ongoing testimony. Even if Janet and the lawyers who hired her were bound by professional ethics not to reveal where they found Martin, it would only take Burke getting to one paralegal to figure out how to track them down, this time with bullets. Their secrets teetered on a razor’s edge.

When things went south for Martin, he usually made things worse. He was out drinking when a barfly guessed Martin was Italian. “Where you from?” the stranger said in Italian. “New York,” Martin answered, also in Italian, screwing up on both counts. “What the hell are you doing out here?” asked the curious guy, this time sending Martin scurrying away.

The marriage to Sherry, which carried a potential bigamy charge, also jeopardized their protection. Even the reckless Martin seemed to grasp this eventually. When he was next in New York for testimony, he tried to do damage control by assuring McDonald he hadn’t really married Sherry. They had had a hot weekend, was all, and then went through the motions, but they weren’t actually issued an official marriage certificate. McDonald grudgingly believed the fabrication.

Martin’s children, meanwhile, were struggling. Gail and Michael each had a best friend from school for the first time since joining WITSEC. But the more time they spent at the Ponderosa, the more Gail’s pal Kathy and Michael’s buddy Chris grew suspicious of the Lewises. Soon Gail and Michael both folded under their friends’ scrutiny and confessed who they really were. Chris immediately disappeared from Michael’s life, representing another avenue for exposure.

Michael, who was bright and hard-working, preoccupied himself with a job busing tables and washing dishes at El Toreador, where Wayne, the owner, took him under his wing. It irked Michael that his dad showed up at the restaurant with his drinking buddies, but the teenager avoided making a scene for fear of losing his job. Then, one evening, a drunk Martin pulled a gun on a cook, whom he mistakenly believed had said something untoward to Kaylen. The terrified cook paled and threw his hands up as Wayne, the owner, approached slowly and told Martin he was going to take the gun away. Martin brandished the pistol at Wayne but allowed it to be taken in the end. Wayne returned it to Kaylen, who promptly gave it back to Martin. The next day, Michael was fired.

Under their own roof lived yet another potential investigator of Martin’s true identity. They had taken in Charles Putnam Middleton, an elderly man who wasn’t expected to live much longer, to earn some extra cash after his family tired of hearing him complain about the nursing home. This income added to their monthly WITSEC stipend and Martin’s drug dealing. Martin thought Charles was “almost a hundred,” which was close; he was actually 97 years old. He was also a former banker and municipal official and the oldest known living graduate of Harvard. Martin or Kaylen would prepare food for him and usually blend it into mush, which seemed a shame to Martin, the proud Italian gourmet. Martin had never seen anyone with such good table manners. Most of the time Charles would sit by the window and take in the fantastic views, but he was far from the senile sack of bones they expected. In fact, he was sharp as a tack.

Any exposure of Martin’s identity in any corner of their lives could create a domino effect, as it had in Kentucky. Only this time, another relocation wouldn’t be in the cards. McDonald had had to beg and plead to keep Martin in the program after Kentucky, and there was no way the feds were putting up with the wiseguy through another move, no matter how crucial his testimony. Their WITSEC cover, which included a cadre of U.S. Marshals who stayed near their house, was the family’s last line of defense against the rest of the world, and one more screw- up could tear it down.

Nick Pileggi was well aware of the danger that surrounded anyone close to Martin. He was given a bulletproof vest to wear when he was with his source, though he declined to use it. At one point, there were fears there could be a potential plot to kidnap Nick himself in order to get to Martin. As usual, Martin made things worse. His involvement in drug dealing, often in the backs of restaurants and bars, wasn’t slowing down, and the DEA — unlike the FBI — had no incentive to protect him.

For Kaylen, paranoia dictated that dangers were everywhere. A nosy teen from Redmond High or the last member of the Harvard Class of 1906 could put pieces together from inside the Ponderosa that Sherry and Janet were putting together from the outside. Driving home the threat, people were still getting whacked in New York. Despite the ongoing trial, two women with tangential connections to the Lufthansa heist had been brutally murdered by Burke’s crew in recent months.

Kaylen, desperate to keep her family out of danger, entered survival mode, which meant circling the wagons. Sherry was a nice girl, but family was family. Kaylen decided the first thing she needed to do was dissolve the marriage of Martin Lewis and Sherry Anders. Pulling Martin by the collar, she marched him to Sherry’s house with papers in hand.

Incredibly, Sherry wouldn’t sign.

Trying to steer out of the fugue of her shattered relationship, Sherry faced huge problems. In addition to still loving a man who bamboozled her and had a family of his own, she was in the hole for thousands of dollars thanks to Martin’s extravagant spending. The phone bill alone, a laundry list of long distance calls to Pileggi and McDonald, added up to $1,400. Hustled by a master conman, Sherry wasn’t about to sign anything until she had an attorney — if she could even afford one.

But Sherry had another reason she couldn’t cut the cord. Out to dinner with Samantha at El Toreador one evening, she felt queasy and excused herself to the restroom. A nagging suspicion was becoming a certainty: She was pregnant.

The news that Sherry wasn’t signing the papers didn’t go over well at the Lewis household. “You’re going to sign these divorce papers today, or I'm going to cut your hair to the scalp. I have the scissors!” Kaylen berated Sherry over the phone shortly after her visit.

Unsure what to do, Sherry told Martin she was pregnant. The man-child who loved kids actually seemed thrilled at the prospect at first, but as soon as he started drinking he grew belligerent. It’s possible Martin told Kaylen about the pregnancy, ratcheting up the fever pitch higher.

Martin’s interactions with Sherry veered between conciliatory and hostile. At one point he openly threatened her over the papers, assuring her he knew people who could take care of her. “They're not going to miss this little hairdresser from Bellevue, they’re going to come in and blow you away.”

Though Janet, the stoic PI, didn’t find Martin intimidating after her months of surveillance — “I thought he was a schmuck” — she observed how frightened Sherry became in the headwinds of the storm. “She thought he was a monster who could kill her in a second.” Janet began to sympathize with Sherry now that she was no longer a target of investigation, and the two struck up an unlikely friendship. Besides, nothing bothered Janet more than men who thought they were above the law, men like Martin. A psychic told Janet that in a past life she had been a pioneering doctor whose innovations were stolen by a male doctor. Evidently, she hadn’t let the sleight go in this life, and now her job became her mission.

Under threat from Martin and Kaylen, Sherry began sleeping with a gun under her pillow, exactly as Martin had when he first entered Witness Protection. One day, Sherry’s 3-year-old nephew pulled the handgun from her unattended purse, nearly giving Sherry’s sister, Catalina, a heart attack.

Sherry was desperate to get Kris out of danger and arranged for him to go to California, but those plans fell through. One of Sherry’s neighbors, an older Asian-American man named Corkie, had a family cabin in the woods on Lake Crescent and offered to hide them there. Corkie was reserved but very protective and paternal, and he had been keeping an eye out for Kris for years. Sherry accepted, and both she and her son holed up. But with her savings depleted, she couldn’t stay long before returning to work. Though he couldn’t fully understand what was going on, Kris knew it was bad. “I was kind of scared for my mom because she was kind of bent out of shape.”

Sherry began to drive her car like she was being chased, shooting down back roads, constantly checking her mirrors, parking behind buildings so her car wouldn’t be seen from the road. It didn’t help calm her down that one of the women murdered back in New York for knowing too much about Lufthansa was a hairdresser just like her, snatched from a sidewalk outside her salon and never seen again.

Back in Redmond, it was hard to avoid Martin. One night, Samantha, Sherry’s roommate, ran into him in town. He pleaded that he still loved Sherry, and with those big puppy dog eyes convinced her to let him in the house. When Sherry got home from work, she found the very man she was hiding from, the man who’d threatened to have her killed.

“I don’t want anything to do with you!” she screamed.

Martin was drunk, as usual, and before she could get him out of the house he toppled over. Unsure what to do, the women placed him in a room to sleep it off.

When morning came and Martin still wasn’t at home, Kaylen, newly vigilant and short on patience, suspected she knew where he was. Dislodging a heavy pipe that was supporting a hammock in the backyard of the Ponderosa, she marched to the car. Gail was terrified.

“Mom, what are you doing?”

“Your father’s fucking that woman Sherry!”

The kids in this household were used to having to parent their parents. “Wait, slow down. Tell me where you’re going.”

“I’m going to bash Sherry’s face in, and then I’m going to beat your father.”

Kaylen pulled up to the split-level in the Lewises’ green Pinto and stormed out, forgetting the pipe. She found the door unlocked — Samantha’s son, Troy, often forgot to lock it when leaving for his paper route, still believing nothing dangerous ever happened in Redmond. Kaylen made a beeline to the bedroom, where she found Martin passed out. She ripped off the covers and dragged him out of bed by the crotch. She spotted the heavy white and gold phone, no doubt recognizing it from their past life in New York, and began walloping him with it.

Next, she went looking for Sherry, whom she believed had slept with her husband the previous night. Sherry was naked in the shower in a separate room when the curtain opened like something out of Psycho. Kaylen began to beat Sherry with Martin’s phone, shouting at her with every imaginable vulgarity.

“I was never so scared in my life,” Sherry recalls. She slipped by Kaylen, grabbed clothes, and shot out the door half-naked. Then she got in her car and zoomed away down side streets.

Not long after, Kaylen stormed into Sherry’s house again demanding she sign the papers. When she didn’t, Kaylen grabbed a fireplace poker and began swinging it at Sherry, who narrowly escaped once more.

In the midst of all the turbulence, Martin’s relationship with his son, always fraught, turned violent when Michael attacked him with a homemade mace. Even Gail, a daddy’s girl from the start, was unable to forgive Martin for what he had put their mother through, the marriage to Sherry a last straw.

At long last, Kaylen figured out how to circumvent Sherry’s cooperation for a divorce. Though Martin had converted to Judaism for her, he was born Catholic, and the Church offered a legal provision for one-party annulments under certain circumstances. The several-month marriage between Martin and Sherry Lewis was over at last.

It didn’t save the Lewises from being booted from WITSEC. Martin’s violations accumulated, and he and his family were soon expelled from the program “based upon... continued arrests and breaches of security.” Martin’s drug dealing business grew, leading to his arrest in a DEA sting. He’d been conducting drug transactions in various locations around Redmond, including Wayne’s El Toreador. Wayne’s phones had been tapped and he was grilled by authorities, another person swept up in Martin’s wake. “A lot of customers asked me to use the restaurant phone when they needed to call somebody important, I let them do it. I had no idea.”

Martin was sent to prison where, he later claimed, he had to dodge at least two attempts to kill him by Vario-Burke thugs who were also there. Eventually he was removed from the general population. As late as 1992, the FBI requested authorization for a wiretap to investigate a credible threat to Martin’s life.

By the time of his Seattle arrest in 1987, Martin’s book with Nick Pileggi, Wiseguy, had been published with fanfare, fulfilling Martin’s prediction of being a bestseller. Gail and Michael, his long-suffering children, could only shake their heads at their father being rewarded for a life that put his family in so much danger. Years after publication, Martin admitted to an astounded Pileggi that he never actually read the book. It took DEA officials a while to confirm that Martin Lewis was Henry Hill, but when the story broke, it broke big. News choppers hovered over the Ponderosa for weeks.

In the limelight, former neighbors in Redmond complained that a gangster would be let loose into their neighborhoods. Sherry’s friend Vivian agreed. “It’s just not a good thing to let them go into any town and be monsters, who they really are, and meet someone like Sherry.” There was also anger about the Lewises’ relatively lush lifestyle in their rambling mansion. Even Martin’s drinking buddies turned against him, with one griping to local media: “He comes across as a real neat Joe Blow, ready to be your best friend. It's always a big grin, always a pat on the back. But what you don't realize is that when he's patting you on the back with one hand, he's got his other hand in your pocket.”

With his typical blind good fortune, the FBI came to Martin’s rescue. They still wanted information and testimony. Although he was convicted on drug charges stemming from his 1987 arrest, pleadings to court by FBI and prosecutors, including Ed McDonald, resulted in Martin being released with just probation.

Sherry went back to the Ponderosa one last time, though it was covertly. She reached out to Corkie, who had hidden her and Kris in his family cabin at the height of their trouble. Would he help her again?

The last time she had passed the Lewis house, she had seen Teriyaki, the horse she had sent over for Gail. The horse, like so much else at the house, had fallen into the Martin Lewis vortex. That beautiful animal was emaciated and neglected, and that broke her heart. Her genuine love of animals always showed her true self, says her friend Sande. “That’s the real Sherry.”

Waiting until about midnight, Sherry climbed Martin’s fence onto the property and crept to the barn, grabbing hold of Teri. She was as quiet as possible so she wouldn’t rouse Martin or Kaylen or the kids, or the curious old man who used to stare out the window. She climbed onto the white horse, all ribs and bones, a shell of himself. Corkie, meanwhile, snapped on the brights of his big green van. He drove slowly behind her, lighting the way for Sherry — a kind of heist of her own — as she rode, bareback, into the night. She cried the whole way.

In the shadow of Kaylen’s attacks and threats by Martin of mob retaliation, Sherry had to get out of Redmond. Martin had poisoned nearly every part of her life, including her lifelong friendship with Samantha. During one of his drunken tirades, he convinced Sherry he and Samantha had slept together. Through it all, Sherry couldn’t escape the fact that she still had feelings for the wild, freewheeling man who swept her off her feet, and the possible betrayal was too much to live with. She severed ties with Samantha, and it would be twenty-five years before they next spoke. Samantha never slept with Martin. It was just another of his lies, tossed around as shields to protect himself.

Near penniless, Sherry took Kris back to her hometown to move in with her parents. Her pregnancy, no doubt affected by the life-and-death stress, ended in a miscarriage. Martin later insisted Sherry had to know more about him than she claimed, including the fact that he was already married. He maintained she seduced him against his will, basically kidnapped him — “she fuck-napped me,” he said more than once — to Nevada to get married in order to try to get his money.

Sherry admits she was painfully naive, but she’s adamant — as are those who knew her — that she was in the dark about Martin’s other lives. He was a professional hustler, a con man, more than capable of getting one over on a gullible lover from small town Washington, and her story is the more credible of the two.

After the fact, Sherry was able to contextualize overheard snippets from Martin’s writing sessions with Pileggi. She realized she had heard where some of the loot from the multimillion dollar Lufthansa heist was hidden. She remains mum on details, but Janet’s dossier on the case showed that Sherry heard the gold was buried under 42nd street in Manhattan. Get your metal detectors out, because that’s the first time that’s been in print.

With the publicity around Martin’s arrest and the release of Wiseguy, Sherry couldn’t help thinking of the man she had spent the past five years trying to forget. It’s hard for her to talk about that period in her life. “It was so devastating I wanted to kill myself, to be quite honest.” She got through it by thinking about Kris and how he still needed her. Introduced by Sande to a movie crew staying at a Hilton she managed, Sherry began doing hair and makeup for film and television shows, and she thrived. She got steady work at a local morning show in Seattle, where she eventually moved.

One morning, Janet, getting great press, as always, came in to make an appearance on the morning show. Sherry came in to do the private eye’s hair and makeup and panicked. “Please don’t tell them who I was married to,” she said, unsure how it would go over with her colleagues.

The reunion brought Janet and Sherry together on different footing, and the former participants in a cat and mouse game nurtured the seeds of friendship planted years earlier. Janet partially filled the void left by the breach with Samantha. It wouldn’t surprise those who know Sherry that she’d be friends with a woman who was once hired to spy on her and bring down her then-husband. “She’s just nice to be around,” says her sister, Catalina.

With a private eye on her side, and freshly motivated to seek closure, Sherry arranged for Janet to help her track Martin down. By this point, he and Kaylen had divorced, and Martin was remarried to a woman in California named Kelly. Janet turned to chasing him once again, this time on behalf of Sherry. Sherry got, as Janet wrote about herself around that time, “the best private detective I knew — me.”

With Janet’s help, Sherry filed a lawsuit seeking compensation for the money he ciphered from her while they were married. Sherry even gave the judge a copy of Wiseguy. Sherry’s attorney, Joy Lee Barnhart, taking on the highly unusual case just a few years into her practice, warned Kris, 22 years old by then, that he’d probably be watching his mother break down in tears on the stand, which Sherry promptly did. But the judge ruled against Sherry, and even ordered her to pay Martin’s legal fees. Sherry felt that Martin’s government connections had pulled strings for him again, shielding him from any consequences for his actions. It wouldn’t have been the first time. Martin never even showed up to court.

Janet took Sherry to see Goodfellas, the Oscar-winning adaptation of Wiseguys. The movie’s unflinching violence frightened Sherry, and when Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill used a line about Kaylen (Karen), played by Lorraine Bracco, looking just like Elizabeth Taylor, the hair on the back of her neck stood up. Martin had used the same line with her. Fascinated with the mobster life dramatized on screen, and still groping to better understand the world that had created her one-time husband, Sherry even accompanied Janet on a trip to New York to attend the John Gotti trial. Gotti, Sherry noticed, seemed to have the same capped-teeth smile as Martin. In the space of a few days, Gotti threw her a kiss and a known wiseguy among the onlookers flirted with her. She hurried right to the airport.

That same year, Sherry did styling for the film adaptation of This Boy’s Life, largely filmed in the town of Concrete, Washington. Robert DeNiro, who in Goodfellas played murderous Jimmy Conway (changed from Burke for legal reasons), was starring. The real Jimmy Burke had been the one who wanted Martin dead and whose lawyers sent Janet to track him down. DeNiro, Hollywood’s Jimmy, found out about Sherry’s previous marriage to Martin Lewis and called her into his trailer to hear her untold story.

Today, Janet lauds Sherry as a survivor. She believes the annulment Martin claimed to get from the Catholic Church was never valid. Sherry can’t recall whether she ever saw paperwork. In that case, according to Janet’s theory, Sherry remains married to Martin Lewis — a man given a social security number and other verifying information by the government, but never declared dead, since he never existed. In a reversal of Martin’s formulation that Henry Hill was married to one woman and Martin Lewis to another, Sherry’s marriage to Henry Hill may have been dissolved, but she remains wedded to the fictitious Martin Lewis.

Sherry saw Martin one final time — it is still hard for Sherry to adjust to calling him Henry, and she wavers between the two in our interviews with her, the only time she or any of the dozens of friends, family members, and law enforcement officials who spoke with us have told the whole story publicly. It was about ten years after their wedding in Nevada when she got a phone call.

“This is Henry Hill.”

“No you aren’t,” she replied. “Henry Hill’s dead.”

She assumed with all the drinking and drugs there was no way he could still be alive. But he started throwing around variations of the F word, which made her reconsider.

“What’s my son’s name?”

The man on the other end of the line answered without skipping a beat: “Kris Gregory Cowin.”

They decided to meet up for lunch at Anthony’s in Everett, Washington, a scenic waterside restaurant. Sherry put her small handgun in her purse and asked a friend to call the police if she didn’t hear from her by two o’clock. If it wasn’t really Martin, it could be one of his old enemies trying to snatch her in a misguided attempt to get to him. If it was Martin, maybe the years of drugs had made him so paranoid he wanted to get rid of her for whatever secrets she might know. At the restaurant, she was comforted to see a table of uniformed police officers who happened to be there on break.

Martin had become a big fan of Sopranos and could critique any episode. He explained that he had recently had a medical crisis during which he almost died. He had a vision that he was at his own funeral and saw the people he hurt financially, mentally, physically. In his vision, Sherry appeared and told him he ruined her life. Martin felt he’d come close to God. He determined he would go around and apologize to all those in his vision.

“I came back and I had a second chance.”

Sherry accepted his apology. He really was two guys: Henry Hill, the callous hustler, and Martin Lewis, a mischievous but sensitive soul whom Sherry, in spite of herself, still missed. Martin lit up a cigarette, even though there was no smoking. “Oh, I’m friends with the manager, he said it was okay for me to smoke,” he explained. The manager came over and kicked them out.

After their meal, Sherry gave Martin a ride when they stopped at a Barnes & Noble, where he signed a copy of his recently published Wiseguy Cookbook, a collection of his favorite recipes. He wrote: You are the love of my life, HH. Sherry, lost in thought, turned around for a moment and when she turned back he was gone. She searched the nearby storefronts and found him in a bar, bragging to the bartender about his wives. “And here comes my second wife,” he crowed.

She dropped him off at his friend’s house by the water. He kissed her hand, saying “I’ll love you forever.” Then he walked away into the dark.

In 2012, he passed away of natural causes, an incredible achievement, all things considered. She’s kept the wedding ring he gave her, which he bought with her money, and the gold-plated phone Kaylen beat her up with.

Kaylen’s fate is more mysterious — although perhaps not unexpected. After she and Martin split up, she chose to disappear from view. Those who knew her in Redmond believe she is surrounded by animals, which is when she was happiest.

Sherry has never fully been able to put her brief marriage behind her, despite everything. “Once somebody has a piece of your heart, I don’t think it’s like a computer where you go in and delete it.” At 68, she feels Martin watches over her, takes care of her the way she briefly took care of him. She’s still looking for “the one,” though she’s no longer meeting men at bars who are pretending to be people they’re not. Now, like the rest of us, she’s meeting people online pretending to be people they’re not.

Sherry recently changed her name, as though in her own private version of Witness Protection. She now goes by Scarlett, along with a last name she’s asked us not to print. She says she’s leaving Sherry Anders behind with Martin Lewis.

“I’m done with Sherry.”

***

For all rights inquiries please email here.