BY MATTHEW BREMNER

for Truly*Adventurous

Detective Kirk Sullivan of the Las Vegas Police Department was slumped at his desk behind a looming mound of arrest reports when the phone rang. It was the head of security at the Four Seasons Hotel, and he had a strange story to tell.

Sullivan was slight, with short, brown hair and lupine features. He was soft-spoken, often wistful, and had the type of enigmatic humor that left you unsure whether to laugh or not. The detective took enormous pride in his work and liked to tell people he had taken a job at his Dad’s hardware store when he was just six years old and had never been unemployed since. “I’d come home from Kindergarten and just sweep the store,” he recalled.

Sullivan had worked nearly every type of case during his 16 years on the force, from vice to traffic offenses, and he had seen every hotel con going: bogus websites, slick crime rings, petty burglaries by hotel staff. But, as he listened to the security team at the Four Seasons that August morning, he realized this crime was far more audacious.

At around 10 a.m., a handsome, lanky twentysomething with floppy black hair and a bluish mole between his eyes had entered the hotel lobby and walked across the polished marble floors to the front desk. His name was Daniel Gold, he told a receptionist, and he wanted his up-to-date room charges. Several minutes later, the man returned to the front desk. “Wait!” he exclaimed with just the trace of an accent. He’d somehow misplaced his room key and needed a new one. He offered up an I.D. card bearing his photo and the name Daniel Gold. “We later learned that he had a separate room,” Sullivan recalled, “where he had a photocopier and printer to falsify documents.”

With a replacement key in hand, the man pretending to be Mr. Gold took an elevator up to the couple’s $4000-a-night suite. As he entered, he heard voices from the adjoining room: the Golds were traveling with their nanny and children. Unfazed, the man left the suite and used a phone in the hallway to call the connecting room. When the nanny picked up, he pretended to be a staff member, telling her that Mr. Gold wanted to see his children in the spa and that she should go down immediately. Once the nanny and children had left the room, he then called the front desk. You wouldn’t believe it, he said, but his room safe wasn’t working.

“I’m in a rush,” he added, “so could you be quick?”

When the real Golds returned to their suite an hour later, the safe was unlocked and more than $200,000 worth of jewels, Rolex watches, and cash had vanished. So had the man.

Sullivan arrived at the hotel several hours later, and the head of security showed him security footage of the suspect. The thief was nonchalant, and he’d picked his targets uncannily well. “Ironically,” the detective told me recently, “the Golds were in Vegas on vacation because they were having their house refurbished. They had taken the jewelry with them so that the builders wouldn’t steal it.”

After the burglary that August morning, suspecting a serial criminal, Sullivan sent a photo of the suspect to other Las Vegas resorts. His efforts to warn them were in vain. Several days later, the room of a famous Vegas headliner was burglarized at the Bellagio, just down the Strip from the Four Seasons.

Sullivan began to think he might have a career case on his hands. Pure conmen, especially those who commit crimes using only chutzpah and charm, are rare in the criminal world, and they present a unique and enticing challenge to law enforcement. Still, the Las Vegas detective had little to go on besides a handful of security-cam photos. It would be a waiting game.

But even the stalwart Detective Sullivan couldn’t anticipate how long this case would take to crack, to say nothing of the caliber of conman he was up against. He also wasn’t aware of just how many other investigators worldwide were hunting the same ghost, and who would soon compose something of an unofficial global taskforce. By the time of the Vegas burglaries in the summer of 2003, the thief had illegally entered the U.S. at least five different times and racked up two convictions for credit card fraud and one for grand larceny while refining his skills to the level of art. He had developed tens of aliases, and he would use these, as well as the four languages he spoke fluently, to steal millions of dollars from the wealthiest clients of some of the world’s most exclusive hotels. In the following years, he would dupe detectives, judges, and prison guards from Switzerland to Hong Kong. One detective would later describe him as being able to “sell snow to Eskimos,” while the British press compared him to famed and fictional crooks Frank Abagnale, Jr., and Arsene Lupin.

Detective Sullivan would be one of a coterie of international sleuths, who — along with this journalist — would become obsessed with peeling away the many layers of this mysterious criminal’s persona in an attempt to answer a seemingly straightforward question: Just who is this guy?

What they’d come to learn is that the man had been a cipher from a young age, practically from the very beginning, when he literally fell out of the sky.

“He had developed tens of aliases, and he would use these, as well as the four languages he spoke fluently, to steal millions of dollars .”

It was shortly before 3 a.m. on a balmy summer night in 1993 when a mechanic at Miami International Airport opened the wheel well of a DC-8 cargo jet as part of a routine security check. When he did, a body rolled out. The plane, hauling flowers, had just landed following a three-and-a-half-hour flight from Bogota, Colombia, and the stowaway, wearing only a T-shirt and cutoffs, was curled in a ball, unconscious and frozen like an “ice cube.” Within 15 minutes, emergency services were on the scene. The first paramedic proclaimed the boy dead, but the second found a weak pulse. He was rushed to the Pan American hospital.

Other stowaways had attempted similar feats. Three years earlier, two Cuban men had frozen to death in the wheel well of a DC-10, and a year later a bloodstained seat was discovered in the well of a Boeing 727. This boy should’ve died, too, authorities maintained, offering no explanation for why he hadn’t. At altitudes of over 30,000 feet, the temperature drops to below minus 45 degrees centigrade and a stowaway would be at high risk of hypoxia, nitrogen gas embolism, and decompression sickness. But this stowaway had suffered none of these problems. In fact, by 6 a.m. that very same day he was already well enough to start talking to immigration officers.

Though he was found with Venezuelan papers, the boy told investigators his name was Guillermo Rosales, that he was 13 years old, and that he was from Cali, Colombia. He said his parents had died six months previously in a bus accident and that’s why he dropped out of school. He had nothing to eat and nowhere to sleep, no siblings, no uncles, no grandparents — nobody. He said he was alone in the world and that he had taken a chance on a better life in America.

The Associated Press and the national newspapers all picked up the story. A Texas woman set up a bank account for Rosales, in which she transferred thousands of dollars. A couple from Washington State called offering to adopt the boy. And an immigration lawyer named David Iverson offered to represent Rosales for free. “I thought he was a very adventurous, fearless young guy, one willing to take his chances,” Iverson told me recently.

Immigration authorities decided not to deport him immediately while they investigated his claims. Jairo Lozano, a Miami police detective, and his wife, Bertha, went as far as to house Rosales in the meantime. The new lodger seemed astounded by the family’s middle-class suburban home. He thought they were millionaires and immediately took to calling Bertha his “Mother,” while she called him “Guille.” “He was always quiet, grateful, and fitted in well,” Lozano recalled.

He also loved the attention. He preened for the T.V. crews that filmed him for a haircut or caught him eating his “first all-American meal” at McDonald’s. He seemed to have a knack for playing the part of the lucky risk-taker, the one-in-a-million boy whose dreams were finally coming true. He was someone who was easy root for, a poor child from a tough place who finally had a mother and father, lived in a real American house, ate home-cooked food, and wanted for nothing.

Looking back, of course, there were signs, little inconsistencies, like the fact that Rosales was 5’10”, exceptionally tall for a 13-year-old. The manner in which he’d arrived in the country also raised questions.

Weeks into his stay, the teenager began disappearing from the Lozano home for days at a time. “We didn’t know where he was or why he kept leaving our house,” Lozano said. On his return, Rosales would say only that he had gotten lost. Toys would go missing, and although Lozano could never prove it, he was sure the boy was stealing them. Bertha also recalled the day when the family went to the 5-star Fontainebleau hotel in Miami for a day out by the pool. On the way back home, she found $200 cash and a gold pendant on Rosales. He admitted he had stolen them from guests at the hotel.

Two weeks would pass before authorities confirmed that Guillermo Rosales didn’t exist. On June 18, Colombia’s security agency faxed the Colombian Consul in Miami with a bizarre update. It appeared the boy’s real name was Juan Carlos Guzmán Betancur and he was 17, not 13. He had an aunt in Miami, and his mother was not dead at all. “I realized that this was a troubled teenager who was not to be trusted,” the Colombian consul, Andres Talero, recalled later. After interviewing the boy, the consul said he had his doubts that he had, in fact, stowed away in the landing gear.

In July 1993, Guzmán was deported back to Colombia. When he arrived in Bogota, a horde of journalists elbowed and shouldered for his story. Anyone who had seen him play for the cameras as a well-meaning runaway in the United States would have been astounded at the transformation as he strolled through the airport. He wore a brand-new suit, slicked-back hair, and a chunky set of Sony headphones. He looked for all the world like a well-to-do scion of a rich and powerful family.

But for Guzmán, who bent the truth almost by reflex, this mask of privilege was just another small lie woven into what would become a Gordian knot of deceit. It would be years before detectives, victims, and this journalist would learn the truth of who he really was.

Soon after the Las Vegas burglaries, on the other side of the Atlantic, rookie detective DS Christian Plowman of the Hotel Crime Unit at Scotland Yard read a small article in the U.K.’s Sun Newspaper. “It was one of those tiny sideline articles, and it spoke about this hotel conman who had been arrested in Paris,” Plowman recalled.

Something struck a chord: Both Plowman and his boss, Detective Andy Swindells, thought it sounded similar to a series of burglaries that had taken place in 2001. Back then, a man had ripped off the Lanesborough and Mandarin Oriental hotels in Knightsbridge, and the Four Seasons and Intercontinental hotels in Park Lane. He had stolen over $80,000 worth of jewelry and cash and spent another $10,000 with a stolen credit card on high-end clothes and a chauffeur-driven Bentley. The thief, whoever he was, seemed a zealot for luxury, the type of person who used Louis Vuitton passport covers, wore gaudy jewelry, and would settle for nothing less than first class. (“Not even business would do,” Guzmán later confirmed.)

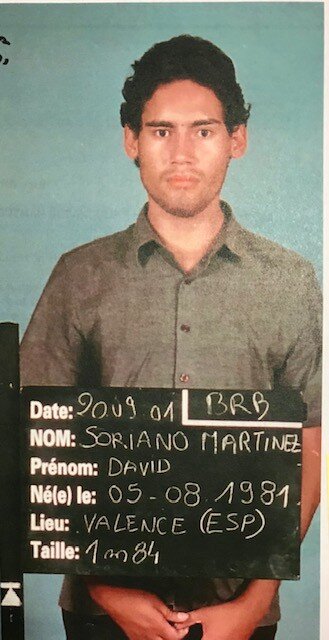

Swindells and Plowman were convinced the man arrested in France was the same man from London three years earlier. They rang the French authorities, who provided them with a mugshot. This picture matched the stills from existing CCTV footage the pair already had. Unfortunately, the revelation came too late. The French authorities informed the detectives that the thief was no longer in their custody.

Disappointed, the London detectives would soon learn that Guzmán had a habit of disappearing and showing up again in strange places. Fortunately — or perhaps frustratingly — they wouldn’t have to wait long for their conman to resurface.

In November 2004, a string of burglaries took place at some of London’s top hotels. On each occasion, the thief would pretend to be a guest, loitering in the lobby, drinking coffee in the lounge, or ordering drinks at the bar. What he was really doing was profiling targets, filching names from discarded checks, and eavesdropping on conversations at reception. He had a keen memory, and an ear for seemingly trivial details. Did a customer have a babysitter for the night? Was it a special occasion, perhaps a birthday? Even details about a restaurant booking could yield an opportunity. With the information carefully organized in the cubbyholes of his memory, and abetted sometimes by a fake ID, Guzmán could assume almost anyone’s identity. In the last of these burglaries, at The Dorchester on Park Lane, he stole around $50,000 worth of watches, cash, and clothes, including a £2,000 Valentino leather jacket and a Frank Mueller watch, which had been part of the victim’s Christmas shopping spree.

“Just reading the reports, we knew it was the same guy,” Plowman recalled. Detective Sullivan surely would have recognized the pattern, as well as his investigators in France and elsewhere, who were increasingly keyed into Guzman’s style. Even so, the detectives had very few leads. They knew what their man looked like and that he was undoubtedly a serial conman of some repute and skill, but like Sullivan in Las Vegas, they still had no way of locating him.

Plowman was frustrated. He had only been a detective for three years but had a hunger to solve cases and ascend the ranks of the police force. Like the man he was now hunting, he, too, had a predilection for adventure and games of deception, and he would later become an undercover officer, assuming the identities of Russian gangsters and aristocratic businessmen. Indeed, for Plowman, the man was like “someone out of a film.” He was confident and glamorous — old-school, even. In the detective’s experience, most mediocre conmen acted exactly how you’d expect criminals to act when they were about to commit a crime. But going through the CCTV footage, he found Guzmán seamless and graceful. “It was rare in that line of work to come across such an intelligent and capable criminal,” he remembered. The more he studied the master conman, the more his obsession with catching him grew.

Over pints of beer at the local pub — perhaps at the exact same time Detective Sullivan was sitting in his Las Vegas office swamped by old INS reports of Guzman’s travails in Miami — Plowman and Swindells would ponder and dissect the crimes. What made him so convincing, so difficult to catch, was his ability to seamlessly assume the identities of his victims, the detetives mused. There was technical nous, yes, and he often used fake IDs, but, as Sullivan would later reflect, he “became” the person he was stealing from.

Thanks to information from Interpol and the French police, they knew their man had a series of aliases and that he had robbed luxury hotels in London and Paris. They also knew he had been working in the UK long before the 2001 robberies. Plowman’s and Swindell’s beat was one of the city’s most affluent areas. The Ritz, Claridges, The Dorchester — London’s finest hotels were nearby, and it seemed impossible that he would pass up the chance to hit the area again. In their growing obsession, the detectives began to imagine what they would do if they bumped into him on the street.

They were unaware they would soon have their answer.

Since his debut as a conman in Miami as a teenager, Guzmán had been busy. He had crisscrossed the globe, leaving a trail of fake identities and very occasionally cropping up in a prison cell or courtroom — albeit invariably under a false name.

In 1995, he was arrested in Florida attempting to board a “crew only” airline shuttle bus using stolen airline identification. A few years later he tried to board a U.S.-bound flight in Ireland with a United Kingdom passport bearing the name Terrence John Marks. In the intervening years, he had hoodwinked staff at hotels in Paris, New York, London, Geneva, and Toronto, stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from some of the world’s wealthiest people. During one of the biggest of those heists, Guzmán allegedly stole half a million dollars from a man from the UAE. “ The crime was never reported,” Guzmán later bragged. “The guy probably had so much money he never went to the police.”

But it wasn’t the amount of each haul or the brazenness of his crimes that made him stand out. For detectives like Plowman in London and Kirk Sullivan in Las Vegas, the best of whom have an eye for nuance, for the craftsmanship and style that the rarest minority of criminals bring to their trade, truly talented conmen are a puzzle, a test of the detective’s problem-solving prowess. The investigation, for men like these, was psychological as much as it was forensic. For an astute detective, each of Guzmán’s crimes seemed to go beyond a calculated targeting of the wealthy. Close examination of his methods suggested he actually came to embody the wealth and effortless privilege of his marks, that his crimes were as much about adopting that role as they were about the loot he invariably hauled off.

In Florida in 1996, for example, he convinced the Bureau of Prisons that he was German royalty and resided in Frankfurt, Germany. In Las Vegas in 2003, during one boozy night out on the strip, Guzmán allegedly tipped a barman a $30,000 Patek Phillipe watch. During the London robberies, Plowman told me, he would wear the clothes and watches he had stolen as he left the hotel premises.

The man was a chameleon, and he had both charm and unflappable confidence. At a five-star hotel in Beverly Hills, an American couple walked in on Guzmán in their suite mid-robbery. As the pair stood aghast in their living room, the Colombian remained calm. He reassured them that he was a member of the staff on a routine check, and that as compensation for the unwanted surprise, he would send up a complimentary bottle of champagne. Guzmán then left the room, went to the restaurant, and ordered the hotel’s most expensive bottle. Before he left, he charged the champagne to the couple’s account.

Guzmán’s friendships over the years were based on lies, or, at best, manipulations of the truth. This made meaningful relationships difficult or impossible. One man, who asked that his name not be used, told me how he traveled with Guzmán extensively during a period when the Colombian had pretended to be the son of a Mexican diplomat. But he also said he was kind, “cultured and incredibly intelligent,” and I sensed he still had affection for him. The pair was eventually arrested in Northern Africa together, which is how the traveling companion came to suspect Guzmán was not who he said he was. Despite their closeness, Guzmán remained a mystery to the man he shared months of his life with.

The lack of stable relationships surely affected Guzmán, but he seemed driven by something more than money with each job, as if by assuming the identities of the wealthy he was fulfilling some deeper need, not only demonstrating that he could exist among these people, but that he existed at all. He built each role with care, sometimes hanging on to one of them for weeks, sometimes becoming so lost in them it was difficult to return to who he really was. The detectives left examining the evidence in the wake of these crimes couldn’t help but look on in awe, yearning to know who was at the center of the riddle and wondering if they had the right stuff to unmask him.

I became similarly obsessed when I first learned about Guzmán in 2018, after reading a small piece about him on a Colombian news site. Soon I was reading reports in papers from Vermont to Paris, each telling a small fragment of Guzmán’s story of charm and plunder. Some listed different names, others different ages, but most described him as one of the most gifted conmen in the world. He was a man, they said, who could escape from prisons as easily as five-star hotel rooms; a man seemingly driven to deceive. And though this made unveiling his past more difficult, it was all the more intriguing for it.

Guzmán, I would later learn, grew up in a cauldron of desperation and missed opportunities. Deprived of belonging, understanding, and an identity of his own, his cons began to appear as masterful attempts to provoke feelings of acceptance, and ultimately to challenge a series of people like me to understand him.

“Oh, you mean the polizon?” The stowaway? replied the waiter. It wasn’t the first time I had heard the word. From the moment I had arrived in Roldanillo, a somnolent town in the lush, sticky Cauca Valley of Colombia, people had said it more times than I could remember. Still, it was curious: Though everybody seemed to know the name Juan Carlos Guzmán-Betancur, they knew surprisingly little else.

As I sat in a coffee shop on the main square of Roldanillo, a few days into my trip, Guzmán was proving as elusive as ever. I had tried to contact his mother, Yolanda Betancur, and while at first she seemed willing to speak, she soon stopped responding to my calls. I phoned and emailed brothers, aunts, and uncles without success. I had spoken to dozens of people by the time I finally tracked down Guzmán’s cousin, Jhon Calzada, who described him as a “genius” and a “legend,” and someone of whom he was “very proud.” Calzada explained that the family situation was tense and that Guzmán had not given him permission to speak to the press.

Still, I had managed to dig up one good lead: Jose Guzmán, Juan Carlos’s half-brother on his father’s side. He lived in the town of La Union, just outside Roldanillo, and was willing to speak to me.

The next day, on the patio of a sprawling bungalow shaded by towering eucalyptus trees on the outskirts of the village, I met with Jose and his brothers. Unlike most people I had spoken to so far, they were open and friendly, and it was from them that I got closest to the center of the mystery.

Juan Carlos, it turned out, was no son of privilege. He was the product of a fleeting affair between Yolanda Betancur and Oscar Guzmán. According to a retired local policeman, Guzmán Sr. was a philanderer and schmoozer who lived in the nearby town of La Union. He had nine children with his wife, who was from a prosperous land-owning family, and although he would officially recognize Juan Carlos as his son, he played no role in the young boy’s upbringing.

Yolanda Betancur was no saint, either. “One day she brought Juan Carlos here, to La Union,” recalled Jose. Jose’s mother was well-off, at least by the standards of her rural surroundings, and Yolanda thought she would do a better job bringing her sons up. “But my mother said no,” Jose recalled. The retired policeman, who was there the day Yolanda tried to give up her son, remembered the “shy, restless” toddler having to face the humiliation of being rejected by both his families.

The last time Jose saw his half-brother was when Guzmán was 13. He showed up saying he was in a bad way and that he needed help, but he didn’t elaborate. Jose told him he would keep an eye out for opportunities, but the teenager never returned.

“In the end, I didn’t know him that well,” Jose concluded as our conversation wrapped up. He suggested I visit Guayabal, a shantytown outside of Roldanillo, the place Juan Carlos actually grew up.

I made the 20-minute drive to the settlement. The area was rundown: Ramshackle huts slouched on either side of a coffee-colored canal running parallel to the swollen Cauca River. Palm trees loomed and lurched overhead and insects hissed and spat from dawn till dusk. Walking along those muddy embankments , the atmosphere was not friendly. People didn’t want to talk; they turned their backs, shouted and slammed their doors, or just feigned ignorance. One person told me that two “gringos” had visited the previous year asking for Juan Carlos. “We thought they might have been DEA agents or hitmen, how do we know who you are?” Another man told me to leave the neighborhood immediately when I tried to talk to one of Juan Carlos’s aunts, who still lived in the area. “She’s not here, and she’s not coming back to speak to you,” he shouted, “Go and find him if you want information.”

Still, some locals did speak to me, albeit surreptitiously and out of sight of their neighbors. They told me that Guzmán grew up in Guayabal with his grandmother, mother, and two brothers. He had attended school in a small, single-story whitewashed building not far from there — though he didn’t make it through high school. Some people remembered Guzmán as introverted and shy: “He kept himself to himself,” a childhood friend later told me. There were others, though, who said that Guzmán was flamboyant in his early years, and one neighbor told the local press that he seemed “gay.” Back then, the Cauca Valley, where Roldanillo lies, was filled with Colombian narcos and guerilla groups such as the ELN and the FARC. The culture was macho and often unforgiving of difference, particularly for a young man. “I’ve known since I was a young boy,” Guzmán once said of his sexuality in the only interview he has given as an adult. He had relationships with other boys, but nobody knew about them. They couldn’t. What would they say? Back then, Guzmán had no one to confide in, not even his own mother, and so he kept his own confidence.

Yolanda Betancur, for her part, had a series of boyfriends and flitted between Roldanillo and Cali looking for work. In a sworn statement Guzmán would later give to police in Miami, he described his domestic life as volatile. At the age of 13, he claimed he was forced to live on the streets because his mother’s boyfriend beat him constantly. “She preferred him to me,” he told officers. For months, Guzmán said he had “no home” and no possibility to get regular work. His only real escape was his imagination. He was obsessed with airplanes and would often tell people when he saw one that he would be up there one day. For him, they must have seemed like symbols of a future escape.

Guzmán first tried to flee to Venezuela but couldn’t get a resident’s permit there because he didn’t have a passport. That’s when he set his sights on the U.S. “I was planning it for five months, I was thinking about it all the time,” he later told officers in a police report. He was working at Cali airport when it struck him: There was a window of time when every plane paused at the top of the runway to prepare itself for take-off. He would hide away in the wheel well of a plane and fly to the USA. It would be risky and he could die, he realized, but it would be worth it if he could escape.

Guzmán would later say that he just wanted a better life than the one he had when he’d been “poor and alone,” when he “was eating trash from dustbins,” in the slums of Cali. He didn’t imagine himself turning to crime. Still, he was good at it, and he would have done anything to attain the life he felt he deserved.

So he climbed into the wheel well and left his old life behind. He had been hopping into new ones ever since.

Towards the end of December 2004, Guzmán was walking down Berkley street in central London. Icy drizzle fell from the murky winter sky and hordes of haggard faces paraded down the grey sidewalk. Guzmán was wearing a long leather Valentino coat and a Frank Mueller watch, both lifted from previous jobs. He was accompanied by another man, with whom he’d been living in an apartment in North London. The man would later claim that he and Guzmán were lovers, although he knew the Colombian only by the name David.

As the two men turned into a Sainsbury’s supermarket, none other than Detective Swindells happened to be walking back from a bar in central London after work. He stopped momentarily outside the market, and as he turned around, his trained eye stopped on something familiar. It was a face that he had only seen in blurry photographs, but there was no mistaking it. The hair was dark and wavy, and there was that mole between the eyebrows. Swindells fumbled for his phone and dialed his partner.

Plowman received the call on the steps of Marleybone Police Station. “It’s him, it’s our robber’,” he said, “I’m sure of it!” Plowman thought his boss was joking. “No, Christian. I’m deadly serious, he’s got that mole.” Plowman, who was at that moment on another case, literally ran the mile and a half from Seymour Street to Berkley Street. He arrived out of breath and nervous. “Where is he?” he gasped. Swindells pointed out a tall man several meters away, looking at fruit and vegetables.

The coincidence was barely believable, but both men tried to remain calm. Plowman went in front so that he could see the suspect’s face; “I glimpsed the mole, and I thought it’s obviously him.” He gave Swindells a knowing nod and strode toward the suspect. “I grabbed him by the arm, showed him my I.D. card, and I said, ‘Are you …’ and then I listed all of his aliases.”

Plowman had memorized eight of the criminal’s names. Guzmán tried to wriggle out of his grasp. “Apples and oranges spilled onto the floor, and he looked crestfallen,” the detective remembered. Several minutes later, a police van turned up and transported the three men to the police station.

A few days later, while Guzmán sat in custody, Swindells and Plowman searched through an apartment on the Lisson Grove Estate in North West, London. Inside the apartment was a trove of evidence. There were fraudulent tickets, boarding pass stubs, forged documents. “My favorite was the Russian passport with his photo in it,” Plowman told me.

While Guzmán had been reticent in early interrogations, he now had little choice but to admit to the London hotel burglaries. He confessed to three burglaries in November 2004 and to being the mysterious thief who had hit four London hotels in 2001, but he continued to use the name he had given at the time of his arrest: Gonzalo Zapater Vives. His belief in his own disguise was so strong, the detectives reported, as to be almost unnerving.

After a trial where he was found guilty, Guzmán was sent to Standford Hill on the Isle of Sheppey, an island of 40,000 people, flat green expanses, and two other large prisons some 42 miles from London. Despite his string of high-profile crimes, which throughout his career are estimated to have netted millions and would have been worth hundreds of thousands in London alone, he was handed only a light sentence of three-and-a-half years. In large part this was due to the fact that he was never physical, never used violence or threats, even if caught in the middle of a crime. None of his identities seemed capable of inflicting physical pain on others.

Reports from prison guards described Guzmán as a quiet and well-behaved prisoner, and he did little to draw attention to himself. That was, until he escaped several months into his sentence. Taking advantage of lax security, Guzmán used a toothache to secure a trip to the dentist, which was all the cover he needed to slip away.

Police combed the area. He had no credit cards and little or no cash. Authorities alerted airports and ports, but there was no trace of him. Somehow he had gotten off the island and onto the mainland.

Back in Marylebone station, Swindells and Plowman received a call from a journalist informing them of Guzmán’s escape. “Our first reaction was we laughed,” Plowman said. His escape surprised neither man.

Several weeks later, Guzmán turned up in Ireland, where he hit the five-star Merrion Hotel in Dublin and stole 2000 euros in cash, a ruby ring, and an American Express card. He subsequently took the credit card to town, where he bought C.D.s, designer clothes, and an $11,000 Daytona Rolex watch.

“I remember we had been reading the paper after the hotel had been robbed, and I saw an article about the escape of an international prisoner near London,” Peter MacCann, manager of the Merrion, told me. “The crimes that the man had committed seemed similar to the one committed at our hotel.” MacCann passed the article on to the lead detective in the case, who showed the newspaper photographs to the hotel staff and confirmed it was the same man.

When Guzmán was found several days later, surrounded by clothes, jewels, and wearing the stolen Rolex Daytona, he insisted his name was Alejandro Cuenca, that he was 25 years old and hailed from Cadiz, Spain. In interviews with the police, Guzmán explained that both his parents had died when he was young and that he grew up in an orphanage in Seville. He claimed he had then “escaped” from this institution at the age of ten, lived on the streets, and had never attended school. He said he had no birth certificate.

“I would have been convinced had I not known for sure he was Guzmán Betancur,” the lead detective on the case, Bryan McGlinn, told the local papers at the time.

Guzmán was a master manipulator, but his fattening criminal record, the increasing urgency of his crimes, and improving police technology were now working against him, as were the growing number of investigators on his trail.

Since the Las Vegas robbery, Detective Kirk Sullivan hadn’t been able to forget about the conman’s brazenness. He had accumulated multiple binders stuffed full of documents from Interpol and ICE, as well as numerous emails from police departments all over the world. “I couldn’t let it go,” he told me.

In January 2005, Sullivan was sent an article from The Guardian newspaper by someone who had been working at the Four Seasons Las Vegas at the time of the burglary. The employee thought the description matched that of the man who had hit them two years earlier. Sullivan contacted Scotland Yard, and there he spoke to Plowman and Swindells, who provided him with a mugshot of Guzmán. That mugshot clearly matched CCTV stills at the Four Seasons.

Plowman told Sullivan that he had become aware of the Las Vegas investigation when Daniel Gold, the victim of the Four Seasons robbery, had read the same Guardian newspaper article, and had notified Scotland Yard. Convinced this was the same man, Plowman put Sullivan in touch with Detective McGlinn in Dublin, who set up a call with Guzmán in his new cell in Dublin.

On the phone, Guzmán was curt. The Colombian had little interest in speaking to yet another cop, especially one that might have something on him. “It seemed like he wanted to hang up,” Sullivan told me. But the American detective was an experienced interrogator and promptly changed tactics. “I started speaking to him in Spanish,” he told me. “I had worked as a Christian Missionary in Guatemala for 2 years, and so my Spanish was fluent.” In his mother tongue, Guzmán began to open up. He was really more Spanish than he was Colombian, he told Sullivan, a reference to his time living in Spain, and wondered out loud if he was to be extradited to the U.S.

The detective pounced on the opening and moved to the topic of the Las Vegas burglaries. Had he hit the Four Seasons? Guzmán insisted he had never been there. So why was he worried about extradition to the United States? Sullivan thought. In the explanation that followed, Guzmán maintained he hadn’t robbed the Four Seasons — only he also mentioned that the hotel was located in the Mandalay Bay.

That was it, the slip Sullivan had been waiting for. The Four Seasons was located in the Mandalay Bay Casino, but Sullivan hadn’t mentioned that. Indeed, if he hadn’t been there, how would he know such an obscure fact? As the detective hung up, he was convinced he finally had his man.

But he would have to wait his turn. The Colombian was sentenced to two years in jail in Ireland for his crimes in Europe. He was later extradited to France in connection with offenses he had committed years before. In a stroke of luck, he would be released in France with the charges in the United States still pending.

Still, it turned out that Guzmán, who had never forgotten his dream of escaping to America, would soon be headed back there.

It was around 8 p.m. on a September night when Guzmán strode into the Irving Oil gas station in Derby Line, Vermont, a tiny village on the U.S.–Canada border. Still lanky, but a little older now, he dressed in blue jeans, a light sports jacket, and a Colgate-white baseball cap. He approached the checkout counter. Guzmán explained to the clerk that his car had broken down just across the border in Canada. He attended college nearby, he added, and had an exam the next day that he absolutely couldn’t miss. Could he borrow a phone book to call a cab?

Guzmán began flipping through pages, looking for cab numbers. Unknown to him, an off-duty Customs officer had stopped by the gas station to pick up a twelve-pack. The officer had been listening as Guzmán talked with the clerk, and he knew he was lying. There was no college nearby, for one, only a high school on the Canadian side. And Guzmán looked too old to be a student.

The officer called for backup, and within minutes a U.S. Border Patrol agent pulled into the parking lot. The agent cornered Guzmán near the cashier and demanded to know his name. As he had done many times before, Guzmán offered up an alias. This time he was Jordi Ejarque Rodriguez, and in his mind he was already beginning to spin a web of lies.

“Juan Carlos is a mythomaniac,” Andres Pachon, the only journalist to interview Guzmán as an adult, would later tell me. Truth and lies merged until they became indistinguishable, and Guzmán’s inventions, by now a way of life, were becoming increasingly outlandish and risky, like an addict increasing his dosage. “He didn’t need to tell any of the stories he told,” Peter Costas, the lead officer of the Vermont arrest, recalled. “Why hadn’t he just asked for the taxi number and gone? Why had he told the store clerk that he was a student, or mentioned his car was in Canada?”

After serving 30 months in the U.S., Guzmán was arrested in Hong Kong, where he was found wandering on the 16th floor of a Sheraton Hotel by a staff member who recognized him from a widely distributed photograph. After his release, he was arrested in France, where authorities claimed the Colombian had stolen €217,000 worth of cash and jewelry from the Hotel Disneyland in the city of Chessy. Through his lawyer, Guzmán protested his innocence, claiming he was in Brazil at the time of the burglary and that because of his international reputation he was likely a victim of identity theft. But French justice didn’t buy his story. The great impersonator who had been impersonated was perhaps too much, even for Guzmán. In March 2019, he was sentenced to 15 months.

Guzmán’s whereabouts are currently unknown. To the detectives who followed him all those years, he remains one of the most skilled and untrustworthy criminals in the world. Kirk Sullivan, now retired from the police and working as a property developer in Kentucky, offers a more somber reflection. “Most of us grow up, we get jobs, we work hard, we care for the people around us. But it’s just kind of like he’s still that little kid that crawled into the wheel well of that airplane.”

Perhaps the biggest insight to the truth of his identity that Guzmán ever offered came in the Vermont courtroom after his arrest for sneaking into the country. Before the verdict, he handed his lawyer a two-page letter. Offered as a way of explaining his actions, he told the court that he had had a very difficult life, especially his childhood. Yes, he had lived “a great lie,” but these “false stories” meant something to him. They were the only method he knew that took him away from the “nightmare” that had been his past.

Though they were lies and ruses, Guzmán’s stories revealed a truth about him; they revealed his genuine desperation and a desire for acceptance; a compulsion so strong he had endured prison and had almost frozen to death in the wheel of a plane. His stories showed that he was constantly on the run; not from immigration authorities, Scotland Yard, the Las Vegas Police Department, or Interpol, but always from a past he seemed unable to fully escape.

Guzmán is still out there. I always come back to that security still from the lobby of Four Seasons Hotel in Las Vegas. He is wearing shorts and a burgundy T-shirt, and he walks gracefully, confidently through the frame, the picture of a man comfortable in someone else’s skin.

Truly*Adventurous, all rights reserved. For inquiries email us here.