Eleven-year-old Victoria has her sights set on playing Little League with the boys. She goes through tryouts and is told to learn to cook. Instead, she changes history.

At 11-years-old, Victoria Brucker planted her feet wide and crouched down to face the large metal machine as it whirred up, ready to deliver a pitch. Her heart hammered inside her chest as the gaggle of boys impatiently waited behind her for their turns.

Victoria was determined to make her local Little League’s All Star baseball team, composed of the best players in San Pedro, California, but the odds were stacked against her. Not only was she a girl–the only girl–trying out, but she was also a year younger than most of the other boys. And she had only played baseball for three years. There were plenty of parents in the community who had made their feelings clear about the prospect of a girl on the team: She won’t be tough enough… She’ll start crying when she doesn’t get on base… She’ll make a fool of the team.

Victoria, also a competitive swimmer, was strong with broad shoulders, a lean physique and had the upper body strength to rival any boy her age. And what she lacked in experience she made up for in grit and intensity. She slid her right hand up the bat, balancing the wooden barrel between her thumb and forefinger. To her, every hit counted, even in bunting drills.

The machine cranked, the whirring grew louder until pop! Out shot a baseball from the metal mouth. It whizzed toward Victoria who took one step toward first base as she stooped to bunt the ball. But her eagerness backfired.

The ball ricocheted upward off the bat, straight into her lip.

There was a sickening crack as the ball made contact with bone. The crowd of boys gasped.

She touched her face, staring down at her bloodied palm as head coach Joe DiLeva raced toward her. Victoria's mind raced: her dreams of playing baseball with the All Stars were over.

That evening, Coach DiLeva reviewed pages of scribbled notes. Insurance salesman by day, Little League baseball coach by night, DiLeva and his assistant coaches had been back and forth over who to pick for their all-star team. Only 13 could make the cut out of the more than 50 who had tried out.

Victoria Brucker showed strong hand-eye coordination and could whack the ball as hard as any boy. Although she was continually the last to be picked at tryouts, she always had an “energetic smile and quick laugh.” But the decision seemed to be out of DiLeva’s hands, since he couldn’t imagine Victoria coming back after her injury. He scratched a line through her name.

That night, Victoria sat dejected at the kitchen table. Her mom, Elizabeth, comforted her after hours spent in the emergency room for X-rays and stitches.

“Girls can do whatever they want to do,” said Elizabeth. “Don’t let anybody ever tell you different.”

Victoria looked up to her mother, a second-generation Mexican-American immigrant who was the first child in her family to be born in the US. Elizabeth's mother had never taught her child Spanish, wishing her to fit in with American society, and Elizabeth had passed the sentiment down to her own children. Elizabeth knew how important identity was in creating a successful, prosperous future. Victoria knew that her mom, along with her stepfather Rick Roderick, took on multiple odd jobs and worked hard to support their family.

Victoria turned to her mom. “I’m gonna prove them wrong.”

Arriving at the baseball diamond the next morning, Coach DiLeva was shocked to find Victoria sitting on the stands next to her mother.

“I’m ready to go, Coach,” Victoria said, her words slurred from her swollen mouth.

When the 50-odd boys and one girl gathered around the coach in a semicircle, DiLeva shouted the names of the roster. Working down the list, he called the name that would make history: “Victoria Brucker!”

After the announcement, as Elizabeth and Victoria walked towards their car, they were approached by the father of a boy who did not make the team. He nodded at Victoria.

“You need to take her home and teach her to cook and clean,” he said.

“She not only knows how to cook and clean,” Elizabeth said, “she can also crochet and play baseball better than your son.”

Even after making the elite team, Victoria found herself benched for most games. She seemed to be stuck in the background, not able to show what she could do. At best, she was given a designated hitter role. To add insult to injury, she was shunned by her teammates.

“The other boys shied away from her,” the president of the league noticed.

Treated as an outcast, Victoria was heartbroken. “She cried and cried,” Elizabeth later remembered. “She would ask me, ‘Why mom? Why can’t girls play with boys?”

But Victoria found ways to rebuild her confidence. She continued playing for another team, the Phillies, led by Coach Mark Grgas. Not only was she a solid first baseman, but she began strengthening her skills as a pitcher. While opposing batters hesitated as they decided how to handle a girl facing them on the mound, she would unleash a mean, sinking fastball.

“She was so savvy,” remembers Grgas, a bear of a man who worked nights at the Long Beach docks. “She just loved playing, and she was great at it. She was very competitive, easy to coach, easy to talk to–and always had a smile on her face.”

When the time came once again to draft the League’s All Star team, Grgas gathered the other coaches at his house. The odds were stacked against the San Pedro community: no team from their southern California league had even come close to reaching the Little League World Series before. But something felt different this time around; there was a scrappiness in the players, a desire to be the best and the drive to win that the coaches hadn’t felt before.

“We’re going to go all the way,” Grgas told the assembled men.

The coaches agreed on two points: first, they were going to make sure this year’s team would be a powerhouse like none they’d produced before, and, second, two players with exceptional skill and leadership qualities were going to be front and center: 12-year-old San Pedro resident, sixth grade slugger Gary Sloan and an underdog who defined resilience, Victoria Brucker.

For Victoria and her teammates, memories of their home field would be forever cloaked in the waft of freshly baked bread. The DeCarlo Bakery backed up onto their center field and the smell of baking would drift over the clipped grass onto the diamond.

Victoria and her teammates started a running challenge to see who could hit the ball over that 10 foot DeCarlo fence. For a long stretch, Victoria and Gary Sloan–a hulking dark-haired, olive-skinned boy with dazzling green eyes who looked older than his years–were tied: eight balls had made it over the fence. Healthy competition, inside jokes and the passage of time brought the squad closer.

Victoria became the team’s power hitter, batting the all-important fourth “clean-up” spot in the batting order. Often it seemed Victoria was part of every pivotal play on the field. Parents, coaches and players noted her power and strength, as well as her intimidating scowl that rattled the opposition.

Between games and practices, the players allowed themselves breaks for the prepubescent romances that come with childhood summers. “I hit the home runs and I had three boyfriends. Well, couple-week fling things,” Victoria would later joke. “Gary was actually the first boy I kissed.”

Gary and Victoria both stood out as team leaders, and Gary became Victoria’s “biggest admirer,” supporting her as she pushed beyond her comfort zone on first base, continuing to expand her pitching resume. Also a pitcher, Gary was “taken aback” at how good his new friend became on the mound.

Victoria’s longest-standing fan, her mother, was never far. In fact, Elizabeth took a job at the stadium snack bar so she could afford to pay for Victoria’s kit. She was determined to nurture her daughter’s talent, and she wanted to ensure she could be at every game to watch.

With a growing list of strikeouts to add to her home runs Victoria earned the nickname “Wonder Woman” from her teammates. The team had an unusual bond, which enabled them to surprise the competition even when they fell behind on the scoreboard. The team's success was a synchronistic parallel to Victoria's own; they were treated as the underdogs and strived for excellence in order to prove their worth. The added scrutiny they faced by having a girl front and center in their lineup gave them a cause to rally behind and an added motivation to prove their doubters wrong.

With a superstar on their team, the Little League World Series, which would be held in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, and had been nothing more than a mere dream in previous seasons, grew closer. There seemed to be magic in the air every game they played, piling up wins as they breezed through the sectional tournament, beating teams from Inglewood, North Venice and El Segundo.

The San Pedro Little League team arrived at the Southern California Divisional Tournament undefeated.

All 14 teams that advanced to the tournament lined up on the Culver City Park baseball field while the national anthem heralded the opening ceremony in Culver City, Los Angeles. Victoria’s team filed into the hallway as they waited to be called out to the diamond. Another team was ahead–Mission Hills, sporting their pristine white uniforms with royal blue piping.

Victoria noticed the other team staring at her, the boys nudging and pointing. At first they were whispering, and then one of them spoke loud enough for her to hear.

“Look, they have a girl on their team! What sort of team is that?” The boy’s comment emboldened the others from the Mission Hills team, who chimed in asking, “What kind of boys play with a girl on the team?” Another added: “They must really suck if they need a girl on their team.”

Victoria’s teammates bristled at the comments. Two of them moved toward the other team with their fists clenched. They were ready to defend their star.

Coach DiLeva stepped in to defuse the situation. “I know you feel fiercely protective of Vicky, and we all appreciate that. But let’s not stoop to their level, okay? Let’s show them on the field what we’re made of.”

The boys reluctantly backed off. Victoria was touched by their protectiveness toward her. After everything she’d been through, after all the comments and jibes, she finally was one of them.

The announcer’s voice echoed through the hallway and the two teams shuffled out onto the field.

An hour or so after the opening ceremony, Victoria and her teammates were lounging on the bleachers waiting for news of their first draw when Coach approached the group, waving a sheet of paper.

“You’ll never guess who we’ve drawn first,” he laughed. Mission Hills.

Victoria felt her stomach flutter at the opportunity to prove them wrong. There were still two hours before the game, and her team dispersed to watch other games in progress. Victoria was sitting with her parents when she noticed Coach approaching her.

Oh great, she thought, He’s come to break the news to me that I’ll be sitting this one out.

Rising to her feet, she braced herself for the familiar disappointment of being overlooked. Coach stopped, inches away, and looked down at her. He held out a ball.

“You're the starting pitcher, kid.”

There were boys in the league who had been practicing their pitching since they were old enough to walk. But Victoria had an intangible intensity that made her an impact player, no matter where she was on the field. During the warmup, Victoria’s fastballs made her stepdad Rick, who squatted across from her to catch, wince.

“How’s she doing?” Coach said.

Rick turned to him. “She keeps throwing like this and they ain’t gonna touch her.”

Once the game started, Victoria stepped onto the pitcher’s mound to face the first batter. Her catcher gave her the signals. She shook her head, no… no… not that one. After a few more hand signals from the catcher, she gave the nod.

Victoria shifted her weight, adjusted her cap, shrugged her shoulders. She took a long step onto her right foot, coiled in tight, her left knee into her chest. With a breath she began the uncoil, whirling forward on her left leg, planting it firmly on the brick-red soil. She pivoted her back cleat, foot so arched her big toe was the only thing left gripping onto the ground. Every muscle in her right thigh was taut. Her left elbow pulled her body around, flinging her right arm and ball through the air like a missile.

The batter swung hard. Victoria braced herself for a crack that never came.

“STRIKE!” the umpire cried. Everything felt as if it were in slow motion as the crowd roared.

Victoria and her team held Mission Hills for five innings. If Mission Hills’ pregame taunts were any indication, they may have planned to target her as an easy out. For Victoria’s first at bat she hit a soaring fly ball through the field and over the fence, bringing home two RBIs. The spectators went wild. At her next bat, the other team intentionally walked her to limit the damage.

“She dominated Mission Hills,” marveled Gary. “She absolutely shut that team down.”

After the ninth inning, a jubilant San Pedro team began whooping and cheering as they left the field under a scoreboard reading San Pedro: 9; Mission Hills: 0. Victoria had pitched a shutout.

Victoria’s star turns were quickly becoming legend far beyond San Pedro’s own locker room, knocking news about the Raiders and the Dodgers and Angels in their hometown sports pages. A San Bernardino County Sun headline read: “Cleaning up on the Boys.” The News-Pilot, the team’s local paper, wrote “Wonder Woman Leads ‘Em.”

“Clearly, this was a star among all-stars,” wrote Bill Cizek, a News-Pilot staff writer, “a special player.”

The team was on its way to Al Houghton Stadium in San Bernardino, the penultimate playoff tournament before the World Series. If they were to reach Pennsylvania to compete for the championship, they still had to beat teams from as far away as Hawaii and Alaska. By this point, Victoria wasn’t just aiming to reach the series. She wanted “to win it all.”

To open the tournament they faced a squad from Sitka, Alaska. Gripping her bat in her hands, Victoria took a couple of warm-up swings and entered into the batting box. She scanned the 6,500-strong crowd and saw a group of women on their feet cheering for her. They were all wearing the opposing team’s jersey but roused the crowd into a standing ovation for her anyway.

In contrast, far above the diamond sat three elderly gentlemen, who leaned on the guardrail. They eyed the long, dark hair protruding from the batting helmet of the cleanup hitter who’d just stepped up to the plate and commented on the boy’s unusual hairstyle.

“Hey, guys, that’s not a guy. It’s a girl,” said another.

“A girl? What’s this world coming to?”

Victoria had other things to worry about. She and Gary–who used to go head-to-head hitting balls toward a bakery–now were in a dead heat over who could hit the most home runs at the highest levels of Little League competition. But Gary had recently pulled ahead. Sloan just took the lead in team home runs away from me and I want it back, Victoria thought as she stood in the box.

The first pitch came in and she swung, passionately, resolutely, and defiantly towards the ball. Crack!

It flew to the right, soaring over the scoreboard for a home run. The three old timers looked at each other and couldn’t help themselves, letting out whoops along with the thousands of other fans.

“Whew,” one of the gray-whiskered men whistled. “So much for the weaker sex.”

Victoria was the first girl to hit a ball out of the park in the field’s recorded history. Her second home run, a solo to dead center, traveled at least 270 feet, clearing the 200-foot fences.

Victoria went three for three with two walks, scoring four times and driving in two runs. During one of the innings, when she was fielding first base, she was distracted by a commotion in left field. A boy around nine years old was running toward the dirt infield. The crowd was going wild, laughing, clapping and cheering. Her teammates began wolf whistling. The boy made a beeline straight for her with a bouquet of flowers.

Victoria went as red as the clay under her cleats, smiling at the boy as he handed her the roses. The picture made the next day’s papers, as did the fact that the team beat Alaska 18-6.

With each win, the crowds grew larger, many of them there to see Victoria, with approximately 1,000 additional spectators every time she played. Fans unrolled a banner that captured the team’s feeling: “A Dream Come True.”

In another pivotal game, Victoria and Gary continued their tag team roles as leaders, with Victoria dramatically tying the game just in time to force extra innings, then Gary pitching for the win. That victory sealed the regional tournament, and for the first time in their team’s history, they headed to the Little League World Series–and not just that, but they would show up with an undefeated record.

The players and coaches alike were exhausted, but they would need to get across the country in less than 24 hours to make the World Series opening ceremony. By 10 p.m., three hours after their win, bleary eyed and dazed, they were on their way to LAX.

By the time the All-Star team arrived with their coaches in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, they faced new obstacles. In their most recent game, a ball hit Gary’s hand hard, injuring his wrist. He would almost certainly not be able to pitch. Meanwhile, most of the kids’ parents scrambled to book their flights to cheer on the kids. But Victoria’s parents couldn’t afford the plane tickets, so they stayed behind.

Victoria could use all the moral support she could get and couldn’t help but feel disappointed that she would be chaperoned by Coach Grgas’ wife instead of her mother. Opponents could no longer be surprised by Victoria’s talent and were preparing accordingly. “Bring her on,” said the shortstop from Florida who was preparing to face her in their first round of the World Series. “We are all ready for her.” If Victoria needed extra motivation, she may have taken it from the opposing coach’s patronizing comment: “We’ve seen her. She’s a good little ballplayer.”

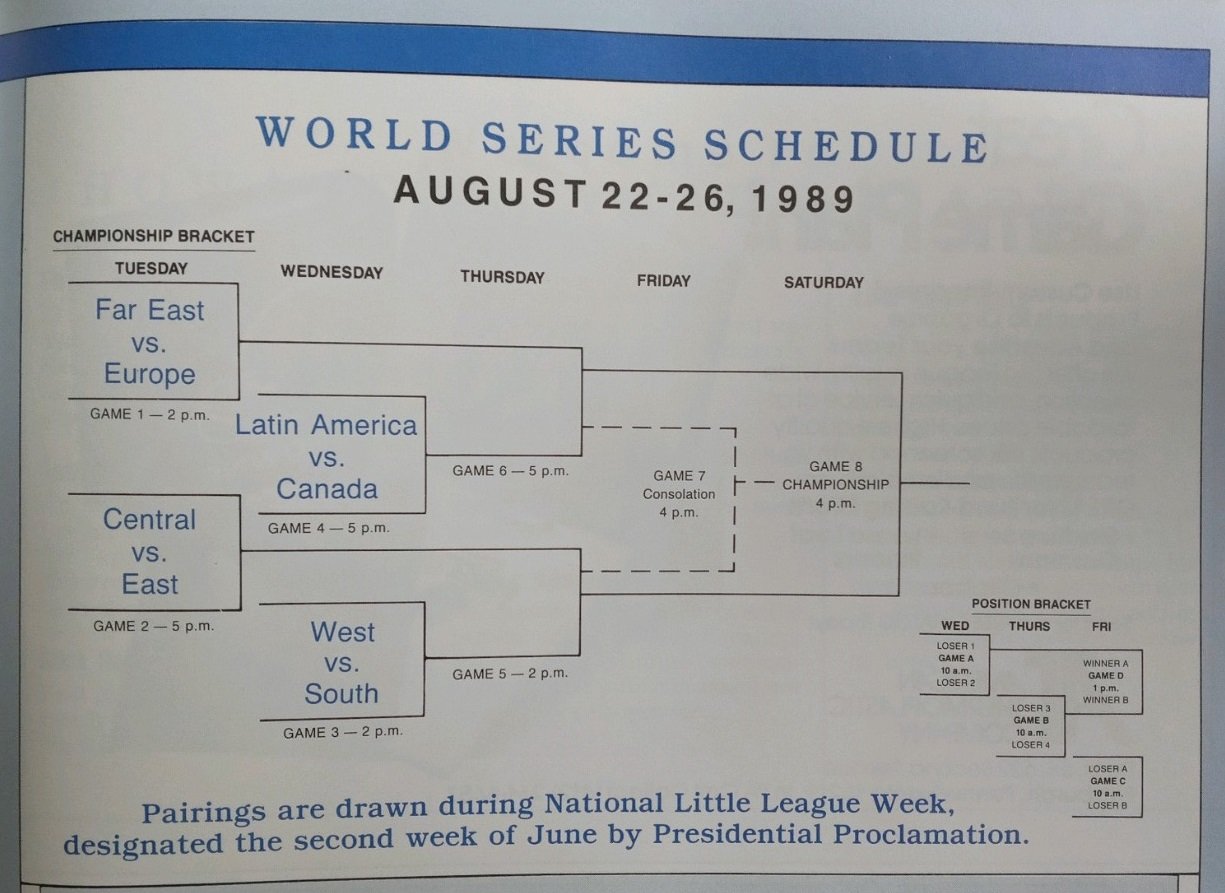

There were four teams from the U.S. represented—the San Pedro team was ‘The West’—and the rest were from abroad. The entire tournament would be played on single elimination: one loss and you go home.

Every team at the World Series was assigned a dorm near the fields, but the dorms were strictly single sex. Victoria had to stay in a nearby hotel, another form of isolation exacerbated by the absence of her parents.

On the morning of the first game, on August 23, 1989, while the coaches gathered outside the complex discussing lineups, a familiar station wagon pulled up. In the front seats were Elizabeth and Rick, with Victoria's brother and two sisters crammed in the back. Victoria’s family had driven 39 hours and 2,637 miles to cheer her on. After a warm greeting, Victoria announced, “I don’t have time to talk,” and hurried back to practice. Meanwhile, Gary’s father had used a combination of tranquilizers and alcohol to get him through the five hour flight, which included an unplanned landing for mechanical problems. “Nothing was going to keep me from getting here.”

When Victoria faced off against the boastful Florida team, she not only made history as the first American girl to play in the Little League World Series, but also as the first girl ever to have a starring role. The underdogs from San Pedro won handedly, even without putting forward their best game, building on the “miraculous run of wins,” as reporter Cizek called it.

Afterward, Victoria was besieged by camera crews and reporters, while her coaches fielded calls from the Johnny Carson and David Letterman shows. Every hit, every play, every missed ball was scrutinized by the media and splashed across papers and TV for the world to see. Her picture was on the front page of USA Today.

Victoria refused to do an interview without bringing her teammates along, but she struggled to get into a positive space with so much pressure on her. After the Tampa game, Victoria’s parents drew the line: no more talking to the press. Victoria began hiding in her teammates' dorm rooms during the day. After a particularly intense day, she approached Coach DiLeva and gave a resigned sigh, “I think I’ve had enough of this,” she told him.

The team–despite struggling with the time zone difference and exhaustion–had scraped through to the semi finals, and they would be playing against the Northeast U.S. team, which was a squad from Trumbull, Connecticut. If victorious, San Pedro would be playing for the world title on live network television, and they would have their work cut out for them. For the past five years, the Tawainese team was expected to repeat. “We have a responsibility to our country,” their manager said. “It is our duty to win.”

Before the big game against the Northeast, reporters surrounded Victoria and her parents, who were helping her carry her bags across the complex to the diamond.

“Do you feel special?” one of them shouted at her, pen poised to capture her response.

Victoria shrugged. “No, I’m just one of the guys.”

“Why didn’t you just play softball?” another called out. Softball, according to conventional wisdom at the time, was better suited for women as it was seen as less physically demanding.

Victoria paused. She had reached the diamond. “I don’t really remember,” she finally replied. “My mom… told me to do what you want to do, and I wanted to play baseball.”

“Victoria eats, lives and breathes baseball,” her mom interjected. “If she’s home she puts on her mitt and drags her brother… outside.”

Victoria disappeared into the dugout, and then she popped out onto the field, ready for warm-up drills. The camera crews and journalists shouted from the fences.

“Victoria, why do you think you’ve not been playing well this tournament? Nerves got to you?”

“What do you want to do when you grow up?”

She didn’t want to answer any more questions, but she would for this last one.

“I want to play baseball!”

Later, at the top of the third inning, the team was down and losing momentum. After hitting back to back solo home runs early, they were struggling to play defense. The Northeast team scored five runs on three errors from the infield in the first inning. DiLeva had to pull the starting pitcher mid-inning.

With the score 5-3 and bases loaded, Victoria had a chance to bring the team into the lead and advance to the final game of the Series. As she stepped up to the plate, more than 10,000 pairs of eyes were trained on her from the stands. Hundreds more watched from the sloping grassy hill overlooking center field. Victoria’s long dark hair was sticking to the back of her neck in the humid Pennsylvania heat. She fidgeted with her uniform shirt, which was cut for a boy.

The pitcher curled up to deliver his first throw.

It went zinging past Victoria.

“Strike one!” the umpire called.

Taking a deep, shaky breath, Victoria reset her stance.

“She’s nervous,” Rick whispered to Elizabeth.

Over on the mound the pitcher coiled up, ready to strike again.

Another pitch sailed past her chest.

“Strike two!”

The third pitch came in. Victoria swung with all of her might.

Ping!

The ball flew off the aluminum bat and headed towards center field. It was a clean hit, but Victoria’s heart sank. It was a fly ball. The fielder tracked the ball against the cloudy sky, and straight into his glove.

“Out!” the umpire called.

Elizabeth and Rick could only watch from the stands as their daughter walked back to the dugout, head down. The team’s home runs had been hit off of the pitcher’s fastballs, so he had switched down to an off-speed pitch. The power hitters, including Victoria, were unable to adjust quickly enough.

The coaches huddled outside the dugout. They would need to pitch themselves back into the game. With Gary’s injured wrist, their options were limited.

“Put Victoria in to pitch,” one of them whispered.

Victoria’s philosophy on such situations was already on record. “When we fall behind,” she told a reporter days earlier, “we always come back. We keep our attitude and work as a team.”

After six years of coaching, this game was a culmination of so much for Coach DiLeva. He had a cigar stored away to smoke after winning this semifinal game and another one saved for the championship. But after considering his choices at the pitcher’s mound, DiLeva declined to give Victoria the call. She was still younger than many of the players. He also sensed this game was not going to go in their favor, and he wasn’t going to destroy her confidence by putting her in during a losing effort. If he put her on the mound at this point, it might turn her off to the game for life. He called up another pitcher instead. Victoria sat on the bench, quietly watching her teammate take the mound. She whooped and cheered him on along with the rest of the team. But somewhere deep down, she couldn’t shake the feeling that she should be the one pitching.

At the end of a long season, the team from San Pedro was fraying, and let another three runs go by before the final out was called. The West: 3; Northeast: 6. Victoria knew she could have hit better during that final game–she swore she’d never let that go.

They had gone further than anyone ever anticipated. But now their dream was over.

Victoria continued playing baseball for another season, until one day, Coach Grgas, who had become close with Victoria’s family, sat her down for a talk.

“Listen,” he told the now 13-year-old. “Baseball’s good. But you know, you being a girl…it’s going to get harder and harder as you get older. But if you play softball, you’ve got a good chance to get a scholarship and go to college. And maybe you need to start thinking about that transition to softball.”

It was a heartbreaking conversation to have with a girl of such talent who had so often been told “no” simply because of her gender. Deep down, he still believed they could have won the World Series if DiLeva had just put Victoria on the mound. Victoria could have handled the pressure, Grgas still believes today. “I’ll say it until the day I die, she should have pitched that game.” DiLeva, for his part, had retired immediately after the loss.

Mulling Grgas’ advice, Victoria knew there was a time to be a dreamer and a time to be a realist. She made no secret of the fact she disliked softball and had publicly said she would be the first female player in Major League Baseball, vowing to beat the odds. But she knew the only chance she had of going to college was on a scholarship. Painful experiences like the car running out of gas and having to push it home in front of other kids, or her mom only being able to put 50 cents of gas in the car at a time, haunted Victoria. “I just knew that my mom was not ever going to be able to afford to send me to college. And we were always told: there is no future in women’s baseball.”

Even if she had led her team to the World Series trophy, Victoria would have smacked into the same glass ceiling. Victoria was playing a losing game, in a way her teammates could never understand.

A few months later, Victoria made the switch to softball, and eventually won a scholarship to play at UCLA.

Not too long ago, Victoria took her kids to Williamsport, Pennsylvania, to show them where mom played in the Little League World Series all that time ago.

Victoria now lives in Iowa–a state without a professional baseball team–with her husband Manuel and three children, Pablo, Paulina and Samuel. Through her husband, she has begun connecting more with her Hispanic heritage—she’s learned Spanish—and finally feels the sense of identity, of belonging, that she lacked all those years ago.

After years coaching a school swim team, Victoria now works grueling shifts for the postal service, sometimes putting in up to 70 hours a week. She would “love” to do something else, but her priority is supporting her family, including encouraging her own children’s athletic endeavors, just as her mom did for her.

These days she occasionally still hears from her former teammates and coaches–mostly to wish each other well on Facebook on their birthdays. Mark Grgas works night shifts as a longshoreman, DiLeva is retired, while Sloan is a father of three living in Denver and working in construction.

At Williamsport, Victoria looks around at the changes. There are girls’ dorms now. Since the Little League Federal Charter was amended in 1974 to allow girls to play, millions of girls have raced around the diamond, but just 20 have made it through to the league’s world series competition. The first wasn’t actually Victoria Brucker, but instead Victoria Roche, a Belgium girl who played in the 1984 series, although she was a backup and did not earn a hit to get on base. In addition to being the first American girl to ever play in the series, Victoria Brucker stands as the first girl to pitch in the World Series, the first to record a hit and the first to contribute to winning a game in the Series.

For such a history maker, however, Victoria’s legacy has been all but forgotten. In a recent television broadcast of the Little League World Series, the commentator made reference to the first girl to ever play.

“But they actually said some other girl’s name,” remembers DiLeva. “And I tried to get a hold of them to tell them they were wrong, I emailed them and everything.” They never responded.

A museum is now located not far from the diamonds at Williamsport, which Victoria and her family toured. But one family member crucial to Victoria’s Little League dreams was missing from the group’s visit. Elizabeth passed away in the fall of 2021 at the age of 73, shortly before she was scheduled to move to Iowa to be with Victoria.

At the museum, Victoria explained to staff members who she was, and offered to donate something for the display. She gave them her precious away jersey from the professional women's softball team she played on for two years, as well as her jersey from playing on the U.S. national team.

But she’s never been contacted again by the museum and the mementoes were never displayed. In fact, there’s no trace of Victoria’s legacy in the museum at all. “It’s kind of upsetting,” Victoria will admit. “I feel like I’ve been forgotten.” Little League baseball, she adds, was not ready for girls.

“I guess you could say I’ve been a little jealous, or upset. It’s been over 30 years since I played in the Little League World Series, and being the first woman to actually step on the field for any real amount of time… and I’ve never been called back.”

Victoria pauses, and adds: “I was hoping they would have thought '[oh, it's our] 25-year anniversary, maybe let's call her back.' Or 30…that’s never happened.”

Baseball hasn’t entirely faded from her life. Last October, Victoria was due to play in a women’s tournament, and spent weeks practicing her throw, even roping in her husband to catch for her. But three weeks before she had planned to fly out to Florida to compete, the competition was canceled. There were four teams, and one from Canada had been unable to travel to the U.S. due to Covid restrictions. In addition, the U.S. Baseball Federation sponsors a women’s national team every other year and hosts training events to recruit and bring up new players. They scheduled an event the same weekend as Victoria’s competition, and many of the competitors had to choose between the tournament and the tryouts.

“It’s ridiculous,” says Victoria. “I was pissed. Why did they overlap it like that? They knew the tournament was going on. If they were really trying to promote women’s baseball they wouldn’t coincide it with events that are so few and far between.”

Victoria, who is still a steadfast Dodgers fan, has no regrets, though. “I am so thankful that I was the first. It was an honor.”

Victoria may still be lacking recognition for the barriers she broke, but she undoubtedly paved the way for the numerous girls who followed in her footsteps to play in the World Series.

That the first two girls to play in the world series were called Victoria was no coincidence. “There’s a reason for that. Our name means victory.”

“You live up to what your name means, and I’ve always tried to live my life like that. I’m still damn competitive. Losing is not part of my name.”

LUCY SHERRIFF is a British journalist living in LA. She writes, produces podcasts, and directs documentaries. Her NatGeo article about beavers parachuting from airplanes in Idaho will appear in 2022’s Best American Science and Nature Writing, and her most recent documentary Born in Prison is available from Topic Studios.

For all rights inquiries, email team@trulyadventure.us.